BY GWENDOLYN REESE, Contributor

ST. PETERSBURG – Currently on exhibit at the St. Petersburg Museum of History is “Fighting for the Right to Fight: African American Experiences in WWII.” The exhibit that opened in October of last year and closes on March 5, tells the story of how thousands of African Americans rushed to enlist at the start of World War II intent on serving their country – even as it treated them as second-class citizens. They were determined to fight to preserve the freedom that they themselves had been denied.

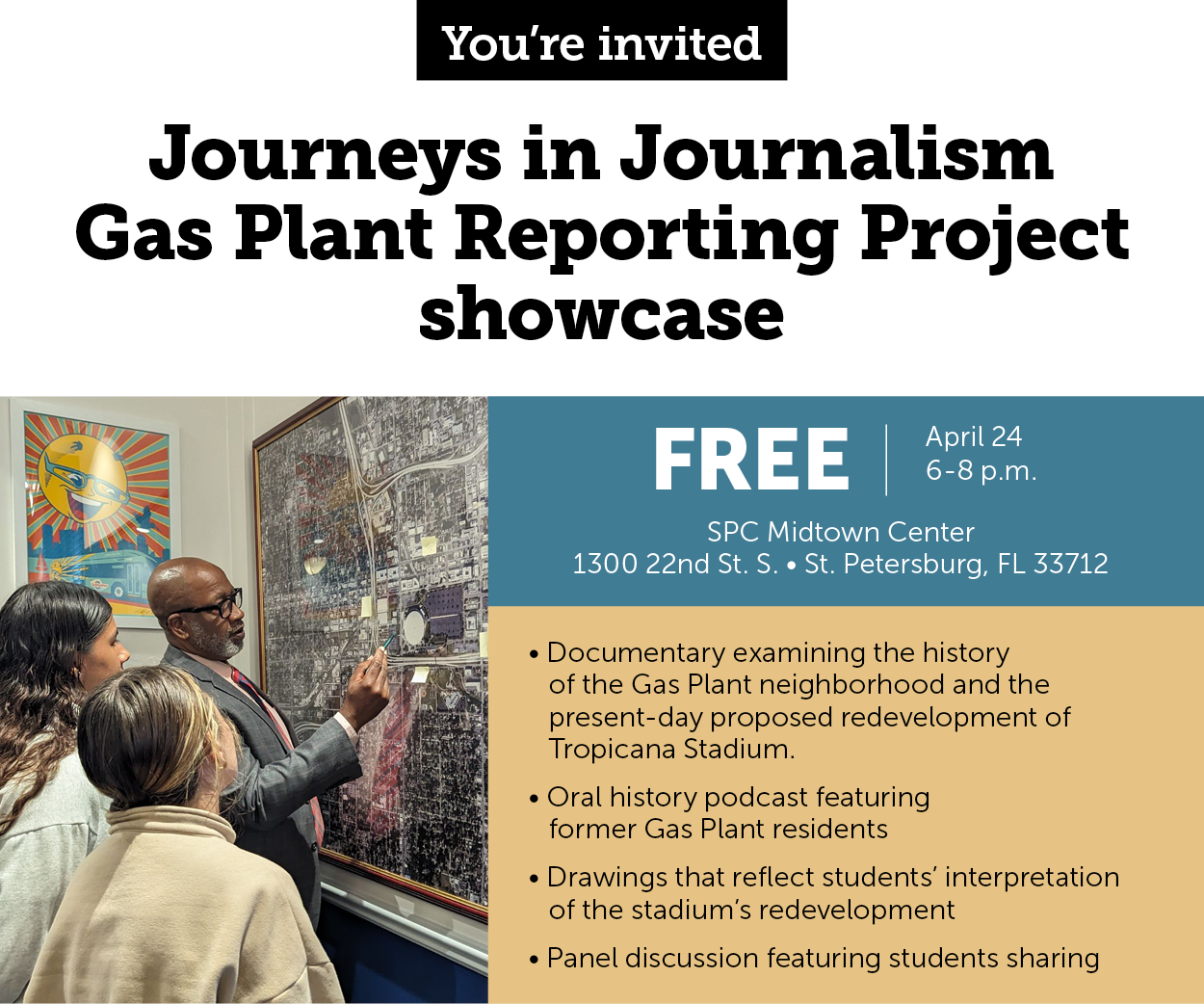

The African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, FL, Inc. along with the Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American History Museum and Gallerie 909 are intent on making sure this story is told and that members of the African-American community can visit the exhibit.

These organizations have collaborated with the Museum of History for a special event on Tuesday, Feb. 28 from 6-8 p.m. that will include the exhibit, a reception and a panel of distinguished veterans sharing their experiences in the military during war and times of peace.

Thanks to St. Petersburg Museum of History Executive Director Rui Farias and museum volunteer Linda Whitley, the usual admission of $15 has been reduced to $6 for this event and children under the age of six can attend for free.

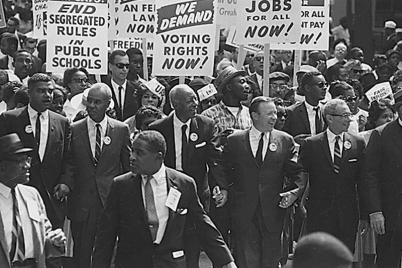

Members of an African-American tank battalion prepare to clear out enemy positions in Coburg, Germany, in April 1945. The 761st Tank Battalion saw 183 consecutive days of combat while attached to General George Patton’s Third Army.

The exhibit originally opened last July in New Orleans at the National WWII Museum. The mission of the museum is to tell the story of the American experience in the war that changed the world, why it was fought, how it was won and what it means today so that all generations will understand the price of freedom and be inspired by what they learn.

After President Roosevelt opened doors for African Americans in the military, more than one million black service members would take part in World War II, risking their lives on behalf of a country that treated them as second-class citizens. Each branch resisted accepting African Americans and racism and segregation was as rampant in the military as in civilian life.

When World War II began, the Army held a deep distrust in the quality of black soldiers. The critical need for manpower, however, forced them to field several African-American combat units during the war, but the overwhelming majority of the 900,000 African Americans that served in the Army during the war were limited to logistical jobs.

The prewar Army Air Corps was more vehement than most of the services regarding the inferiority of African Americans. The Air Corps was adamant that blacks could not serve as combat pilots. However, bowing to a presidential decree in 1941, the Air Corps began training a limited number of pilots at Tuskegee, Ala., the legendary Tuskegee Airmen.

The tradition-bound Navy initially resisted accepting black service members then enlisted African Americans but denied them proper combat training and limited them to the roles of a stevedore, steward or cook. Nevertheless, recruitment surged; more than 160,000 African Americans would serve in the Navy during World War II.

Initially, the Marine Corps strongly resisted the inclusion of African Americans, and limited black troops to supply and logistical roles. Black marines found themselves in some of the fiercest fighting of the Pacific War, including Peleliu and Iwo Jima.

Of the nearly 5,000 African-American coastguardsmen who served during the war, half of them received billets at shore stations or as beach patrolmen. The other half went to sea, most of them as officer’s stewards, though they also manned battle stations as gunners, loaders and ammunition passers.

The Merchant Marine was technically outside of the military and was much more lenient in employing African Americans. Black mariners could sign on to any billet in which they were qualified, though some shipping companies employed by the U.S. government still required that crews be segregated by race.

Please come out and experience the extraordinary achievements and challenges of African Americans during World War II, both overseas and on the home front.

Thanks to individual sponsorships from Carl Lavender, Carla Bristol, Whitley and myself, Gwendolyn Reese, veterans are invited to attend the event for free. Guest invitations are limited to the first 40 veterans to respond.

If you are a veteran and you would like to attend or to participate on the panel, please contact me at (727) 418-2881 as soon as possible.

Post Views:

3,958