Local historian and columnist Gwendolyn Reese is the president of St. Pete’s African American Heritage Association.

BY HOLLY KESTENIS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — On Tuesday, March 22, 1960, 13 well-dressed LeMoyne College students were arrested by the Memphis, Tenn., police for visiting the Brooks Memorial Art Gallery in the Overton Park neighborhood. Seven were arrested for entering the museum and six students were arrested outside.

Those who entered the space on an “all-white day” were charged with loitering, disturbing the peace, disorderly conduct and threating to breach the public peace. These protesting black students had the audacity to enter a public space on a day other than the city’s “Negro Thursdays.”

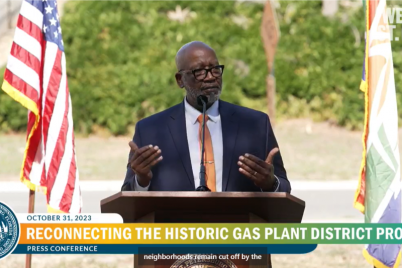

L-R, Jason Jensen, principal of the local-based Wannemacher Jensen Architects and Mario Gooden, principal of the New York-based Huff + Gooden Architects

Mario Gooden, an award-winning architect and professor at Columbia University, told the Brooks story to city council members last month. He said the Carter G. Woodson African American Museum is part of the lineage of black museums that rose out of that shameful history of our nation’s past.

Gooden and others reported to city council on the plan to more than double the size of the current museum that sits at 2240 Ninth Ave. S. Local firm Wannemacher Jensen Architects have been selected to expand the space, and has partnered with Gooden’s New York-based company.

On Saturday, June 22, Gooden brought together local and national historians, architects and the curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., for a one-day symposium to formulate ideas on the Woodson expansion, which is estimated to cost $10 million.

“You have certainly done an amazing job in capturing the essence of forcing us to think outside of the box,” said Terri Lipsey Scott, executive director of the Woodson, to Gooden.

Senator Darryl Rouson secured state funding in the amount of $250,000 for expansion plans in the 2018-19 state budget, but was not so lucky for 2019-20. Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis vetoed the project, and $200,000 of the $250,000 was used in the conceptual phase, which is slated to be complete next month.

Gooden aimed to have an inclusive conversation with experts and community members regarding African-American cultural production and the making, writing and collecting of black history, and let’s just said he knocked it out of the park.

Local historian and president of the African American Heritage Association, Gwendolyn Reese, reminisced about the historic Manhattan Casino where the likes of Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald, Otis Redding and many other entertainment giants graced the stage of the very room the symposium was held in.

She can recall generations of stories handed down from family and community members.

“Our history has been forgotten,” Reese said, pointing out that there’s little evidence of black contributions to the city’s landscape. “We can look all around us and see evidence of that.”

Community members at the well-attended event were invited to take part in the conversation of what they would like to see at the museum and how it should look. Guest speakers all chronicled their journeys of bringing black history to light in the everyday, not just behind museum walls.

Walter Hood is professor and former chair of landscape architecture at the University of California, Berkeley and principal of Hood Design Studio in Oakland, Calif.

Walter Hood, a landscape architect and director of Hood Design Studio in California, has traveled the nation and worked with museums in top cities.

“In landscapes, you see connections. Our lives are intertwined,” he said.

He discussed periods of neglect and how during these times, it is as if the black voice is silenced only rearing its head during extreme marks in history such as emancipation, reconstruction, civil rights or the election of President Obama.

“I think we are in a period of neglect right now,” he explained. “When we had that period where we could seize the moment we did, but then we fall back into the rut. We’re really good at forgetting things.”

His mission? To discover how to make people aware and remember. Taking risks, stepping outside the ordinary and going beyond the expected are what he’s calling for.

“We can’t be stereotypical, we gotta be atypical,” he said.

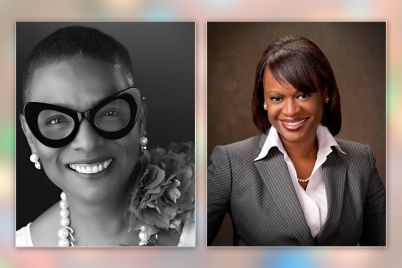

Dr. Michelle Joan Wilkinson, a curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Michelle Joan Wilkinson, a curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, feels the same. Responsible for expanding museum collections in some of the nation’s top museums, she has extensive experience in curating exhibitions reflecting African-American culture. Her interdisciplinary work spans art and history museums and the terrains of African-American studies.

She wants to preserve black history all over the nation and encourages those who live in St. Pete to do the same.

Wilkinson shared how engaging important topics with community members and collaborating and partnering with others can produce needed funds. She generated interest in her own museums by thinking outside of the box, bringing up attendance and competing with other attractions vying for the same tourist dollars.

They did the typical — brought in experts on management and fundraising strategies. They had write-ups in all the papers, spots on television and radio, but it wasn’t until they brought the museum to the community that they really saw a difference.

Museum artifacts were brought into schools, a curriculum to support tours for K-12 students was created and even a touch tour was implemented for a hands-on experience. Live jazz bands were hired, summertime programs were held in the museum alley and artwork installed outside.

“Super scary to do but very memorable,” said Wilkinson. “It was a very proud moment at the museum.”

But what really enticed the community was involving them in the museum itself. Wilkinson scoured the area for potential donors in possession of artifacts they’d be willing to share with the museum. She held antique roadshow events in cities across the country where community members could bring items they cared or were curious about. The museum provided artifact conservators to inform how to best store and care for the objects.

“It was the key to building community investment in the museum,” she asserted, noting the additional bonus of demonstrating how to value history through safeguarding materials of a culture is a lofty goal.

An idea that could take root locally because it encourages artifact owners to protect and care for the items they’ve acquired.

Wilkinson spoke on considering broadening sections of the Woodson to include science, technological achievements, architect, design, as well as coordinating displays to appeal to the eye and tell a story. An idea Reese can get behind.

Woodson Executive Director Terri Lipsey Scott and City Councilmember Steve Kornell

She recognizes the need for black history museums to bring awareness on a national and state level, but Reese stresses the importance of local black history as it tied into what was happening in other parts of the nation.

“Our stories are messy, they’re complicated, they’re beautiful and they must be told,” she said, enforcing the need for those who lived it to come forward and tell it like it was. Reese is adamant that local black history be portrayed accurately and not from the vantage point of a historian.

“We will not let our history be covered over, whitewashed,” she said, recognizing that the Woodson is dedicated to capturing and preserving the rich local history. “It is our job to tell our story.”

For instance, nationally there were sundown cities spread throughout the United States. These were towns that prohibited blacks from walking city streets after the sun went down.

“Well, we were one of those,” averred Reese, betting on the fact that most residents today are unaware of the city’s darker history. “At sundown, we couldn’t be in downtown because that wasn’t the picture they wanted tourists to see.”

Reese used the lynching of John Evans in 1914 in front of the then-courthouse on Ninth Street South and Second Avenue as a prime example. The killing of Evans was reportedly carried out by some 1,500 residents at the time and advertised as upholding the law. Talk on the subject is still often silenced. Museums help ensure the past is brought to light so that lessons can be learned, healing can begin and negative actions not be repeated.

Dr. Mabel Wilson is a scholar, designer and artist. She is a professor of architecture and Columbia University, a co-director of Global Africa Lab and a faculty fellow at the Institute for Research in African American Studies.

Dr. Mabel Wilson is a professor and author of “Negro Building: African Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums and Building Race and Nation: How Slavery and Dispossession Shaped America’s Civic Architecture.” She tells of early museums often being in private homes due to the sundown laws and laws forbidding African Americans from owning land.

When writing her books, she wanted to find permanent places where black history was displayed, but also realized she needed to look at the temporary ones.

Wilson has always been interested in how black history is hidden, and likes to tell stories, “not only as blacks, but as part of the American experience and the legacy of the modern world.”

She explained that African Americans are often fighting the stereotypical images that are circulating, such as working on plantations that continually rob people of their dignity and opportunities. She found it challenging to find authentic artifacts representative of positive black culture as so many pieces remain hidden, locked away in personal collections, not owned by black folks.

Breakout groups moderated by Hood, Wilson and Wilkinson to hear local input rounded out the afternoon. The symposium was a success and lived up to the museum’s promise to engage a broad and diverse audience through activities and to promote an understanding among various groups that make up the fabric of St. Pete.

Lipsey Scott said the expansion will be paid for with public and private money.