BY LYN JOHNSON, Publisher

ST. PETERSBURG – Fifty years ago today, The Weekly Challenger came into existence. My father, Cleveland Johnson, Jr., borrowed $40 from a friend to keep a months-old publication alive called the Weekly Challenge after the owner M.C. Fountain passed away. He added an “r” and the rest is history.

In the mid-1960s, Johnson began working in advertising for Fountain’s small publication called the Weekly Advertiser. He found that he had quite an aptitude for selling advertisement. Being a salesman was in his blood. His father was the first African-American realtor in Pinellas County and sold homes to many of the leaders in the black community from his office on the Deuces.

Although born in Thomasville, Ga., in 1927, he considered himself a St. Pete native, moving here with his parents in 1934. He attended Davis Elementary and Gibbs High School. My father always said he graduated from Gibbs, but the truth be told, he dropped out before his senior year.

Another truth, he had a learning disability. If he were to be diagnosed today, doctors would probably call it dyslexia. This is probably why he constantly played hooky starting in primary school, eventually giving up on the whole institution.

Before dropping out of high school, he got an older woman pregnant and my half-brother Bennie McCall was born. Later, he and Christine Childs sneaked off and got married behind their parent’s back, and from that union produced my other half-brother Tyrone Johnson.

All this happened before he dropped out of high school, before he was drafted and discharged from the United States Army and before meeting and marrying my mother, Ethel Johnson, née Burnett, in 1958.

In the early years of their marriage, he jumped from job to job. He worked at a cafeteria in downtown St. Pete, sold dresses and jewelry out of the trunk of his car, opened a consignment shop and was even a pest control technician.

In the early 1960s, he found a friend and mentor in Fountain, who owned Fountain Printers on 16th Street South. He began selling advertisement for Fountain’s Weekly Advertiser in 1964. Here is where my father found his calling.

The two worked so well together that when Charlie Mann, a coordinator for the Community Service Foundation in Largo, suggested that a newspaper be created that focused strictly on African-American news, Fountain and my father jumped at the offer for an interest-free loan from the foundation to get the ball rolling.

Unlike the Weekly Advertiser that ceased publication in 1966, the Weekly Challenge would feature actual news articles with St. Petersburg Times reporter Mamie Brown heading up the reporting. The first publication date was Sept. 21, 1967. It would have been printed at Fountain’s print shop, but he was hospitalized the week before so the Dunedin Times printed the first 4,000 copies of the new publication.

Fountain never regained his health so my father completed the paperwork and paid the $40 fee to have the business put in his name. He successfully built a newspaper on spotlighting the positives in the black community.

Up until 1967, African Americans in Pinellas County were hard pressed to find positive and uplifting news about themselves. The St. Petersburg Times had the “Negro news page” in which they featured stories about weddings, clubs and schools, but other than that, African Americans made the news as criminals or oddities.

In a history written about the Times’ first 100 years of existence, then deputy metropolitan editor Robert Hooker wrote: “The Times treated blacks like most American newspapers did: When it didn’t ignore them altogether, it exaggerated their deficiencies. Occasionally in the late 1890s and early 1900s, the paper had a column of “colored news.” It was short-lived, however. For the next 40 years, the city’s black residents virtually disappeared from the paper, except when they were involved in crime. That was covered so thoroughly that the word “Negro” (usually not capitalized in a headline) became synonymous with “criminal.”

Hooker wrote that the words “nigger,” “darkies,” or “burr heads” were often used. The only positive news about African Americans was relegated to the “Negro news page” that was only circulated in black neighborhoods. By the time 1967 rolled around and integration began to take hold, the page was discontinued.

“Black news now competed with the rest of the news, and an event that once warranted a few paragraphs on the Negro page rarely made the paper anymore,” wrote Hooker.

The Weekly Challenger stepped in and filled the void. Instead of one page of positive news, the Challenger started off printing four to eight pages weekly, growing to a 32-page publication by the 1980s.

Never did you see a negative story about black people, and never will you see one. He always said, “If you want to read about black people doing something bad, pick up the St. Pete Times, but if you want to read about black people doing something positive, pick up a Challenger.”

Black men must sell as well as buy or else remain a beggar race

That tagline remained on the front page of The Weekly Challenger until my father’s death in 2001. That was his credo and he believed every word of it too.

He lent money to countless numbers of people in hopes that would become business owners. Many times he never saw a dime of that money returned, but he was aware of that going in.

In the early 1970s, my father met a young man by the name of Aaron Williams. He knew Williams had a sharp mind and should be in business for himself. In typical Cleveland Johnson fashion, he told Williams to “leave them damn niggas alone” at the economic development department of the city.

“I said, ‘Well Cleve, I have nothing to … you know … for collateral.’ He says, ‘OK, I’ll do $10,000 and you pay me back.’”

Little by little, Williams paid him back every penny, and his business, Suncoast Hair Care Center, still sits on 34th Street South almost 40 years later.

“I would go to him for counseling … this man had a knack that very few people had. I don’t mean with a business degree, just a go-get-‘em to maintain and sustain his business,” said Williams, who took my father’s creed to heart.

My father mentored Williams in a way that Fountain mentored him. He’d hang around the office and my father would put him to work. Williams shared a story I’ve heard all of my life.

Aaron Williams

“We went to get an ad from JCPenney’s over in Tampa. They kept us waiting a long time. We sat there and finally somebody came out and said, ‘Sorry, but we don’t see how we can do business with you.’ Cleve said to him, ‘I’ll tell you what, if I don’t have an ad in my office by the time I get back there, I’ll have 100 niggas in front of every JCPenney’s you got, picketing.’”

Williams said my father walked out of that office just as confident as he walked in, and by the time the two of them got back to St. Pete, the advertising agency for JCPenny’s had called.

One story Williams relayed that I had never heard before was about his side project called the Inflation Fighter. For reasons unknown to Williams, my father started up a free publication separate from The Weekly Challenger.

For about five years, the Inflation Fighter hit the streets with Williams’ name on the masthead as editor-in-chief.

“We’d lay it out right there in that office like we laid out the Challenger. We’d take it to the printer, and then I’d throw them.”

“I’ve survived 37 years following some of Cleve’s advice,” Williams said.

Lifelong friendships

Forty-five years ago, Mary Murph founded the Sickle Cell Disease Association St. Petersburg Chapter in response to the lack of information available. Considered a black person’s disease, money was not readily made available for research or awareness.

This was unacceptable to Murph. Her two daughters had been diagnosed and she made it her life’s mission to learn how to manage the disease and spread awareness.

She eventually appointed Martin Rainey as chairman of the organization in the early 1980s, and that is when he came in contact with my father. They struck up a deal that every time something noteworthy happened pertaining to the disease, it would be published.

Once my father became chairman of the Southeast Black Publishers Association, he arranged for Rainey to be placed on the agenda at one of their meetings. From that moment on, any news about sickle cell could be seen in papers all throughout the state of Florida.

Sickle cell awareness began to spread. Other Florida chapters popped up and by the end of Rainey’s seven-year administration, 22 sickle cell foundations had come into existence from Pensacola to Key West.

“Your father was the catalyst for bringing sickle cell to the forefront in the state of Florida,” Rainey said.

By working together to spread awareness of sickle cell, Rainey and my father became fast friends. They both shared a love of music and ended up sponsoring and promoting jazz jam sessions together.

My father lived for jazz. From a small child, I can remember listening daily to the collaboration of songs sung by Ella Fitzgerald with Duke Ellington and his orchestra in accompaniment. “Take the “A” Train,” “Mood Indigo” and “It Don’t Mean a Thing” became a part of my everyday soundtrack.

Rainey and the Downbeats were booked solid in venues throughout Pinellas County. My father enjoyed promoting the band, especially when his son Tyrone would pick up the saxophone or the flute and join in.

His love of music started at a very early age. He took private piano lessons here in St. Pete throughout the school year, and when his parents would follow the tourism industry to New York for jobs, his mother, Evie Johnson, née Rhodes, enrolled him in summer courses at The Julliard School.

He was trained classically at Julliard, but jazz was the only music he was interested in.

His love of jazz led him to team up with jazz great Al Downing and form a supergroup. With the exception of Rainey, all 18 members were band directors. For about five years, this group delighted audiences around Tampa Bay.

My father didn’t perform with any of the bands, promoting them was good enough for him. He was just happy to be around the music.

“I mean, everywhere we went all you could hear was jazz. He played nothing but jazz on his radio,” recalled Williams, who said he was first introduced to the genre by my father.

A sharp dressed man

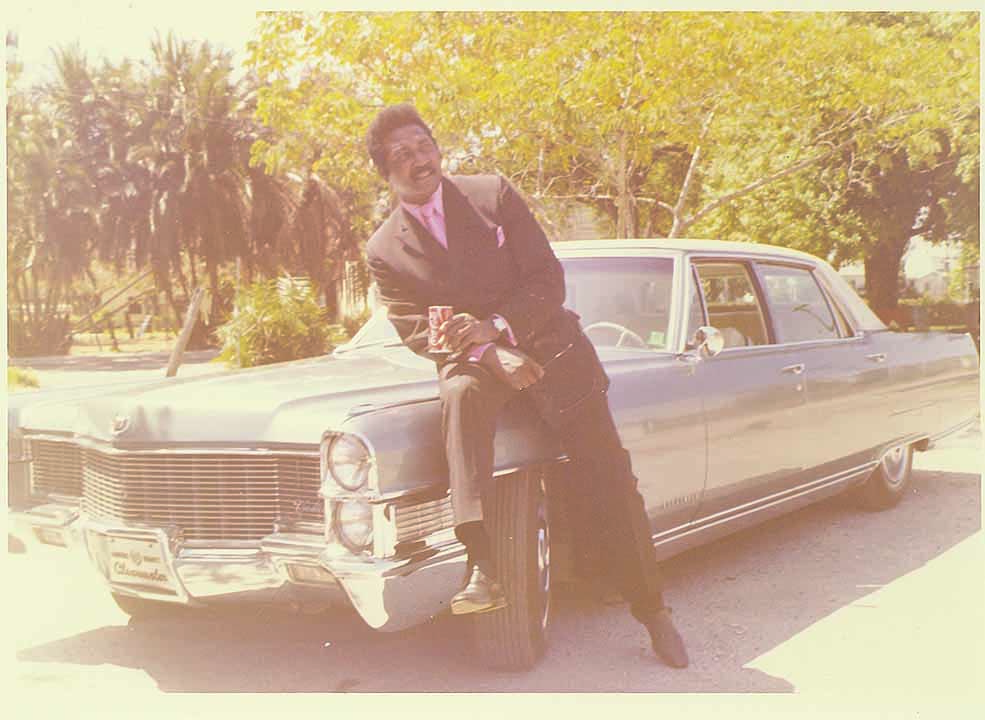

Since I became publisher of The Weekly Challenger in 2012, I’ve had scads of people approach me to tell me about their experience with my father. There are always two common topics of conversation: his clothes and his Cadillacs.

He had a custom-made suit for any and every occasion, with shoes to match. My mother had to have a separate closet because his clothes and shoes overtook the master bedroom walk in.

“He walked around the corner in a canary yellow suit,” laughed Harry Harvey, his friend of 30 years. “You don’t find many dark-skinned men wearing yellow and look good.”

Harvey became friends with my father in the early 1970s. He worked as a juvenile parole officer at an office down from The Weekly Challenger on Ninth Street (Martin Luther King Jr. Street).

“He would go and buy food and would come back and say, ‘let’s eat, let’s eat.’ I’d sit there and we’d eat and talk. I can get talking about that and get tears in my eyes because he made you feel like you were somebody,” he recalled.

Harvey and my father both entered the Mr. Wonderful Contest sponsored by the St. Petersburg Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority. Neither one of them won.

“I was always messing with him about his dress,” Harvey said, noting that my father would always talk it down.

That man spent more time in front of the mirror than anyone in the house, especially when a newly tailored suit arrived.

During the 1980s, his favorite tailor was Angres Chapman, who set up shop in downtown St. Petersburg in 1947. As a black man living in segregated St. Pete, Chapman became one of the first African Americans to set up business in the area.

After leaving the city for 29 years, Chapman returned and my father became one of his biggest clients and closes friends. Those flamboyant canary yellow and lime green suits all came from his shop.

My father loved clothes. As a young man, he sold women’s clothing in Miami out of the trunk of his car. He did so well that the wholesale dealer he worked for told him if he’d been a white man, he’d be rich.

When he moved back to St. Pete, he’d still make Miami runs to pick up the latest fashions and continued selling them out of his trunk. In the 70s and 80s, during the height of the newspaper, he continued to sell clothes, costume jewelry and even opened a wig shop. He was really into fashion.

He was also really into his Cadillacs. He bought his first used Cadillac in the late 1950s.

“He told me,” said Williams, ‘my first Cadillac, boy, I had to tie the door with a clothes hanger, but it was a Cadillac.’”

My mother remembers those days when he would ride in on fumes to the gas station and only have 50 cents to put in the tank.

My mother remembers those days when he would ride in on fumes to the gas station and only have 50 cents to put in the tank.

“Boy, I could just put enough gas in there to get to the next gas station sometimes,” he told Williams.

Every other year, he upgraded to a barely used car until he bought his first brand spanking new Cadillac in 1977.

During the process of writing this article, I found out that I’m actually a distant cousin of Murph. She and my father are second cousins. So I asked her for a funny story and she delivered.

When Murph went into labor with her oldest daughter, her husband, Amuel Murph, was overseas in the army. My father was the only one around with a car. He wasn’t about to let her give birth in his car, so he went speeding through the streets of St. Pete.

“He was trying to hurry up and get me out of there,” laughed Murph.

***

Many of his former employees have retired, moved away or passed on. His office manager and right hand Cynthia Armstrong passed away in 2002, advertising guru William Blackshear retired and left the area and political genius and ad man Lonnie Donaldson also passed away.

There are still a few around such as Jeanie Blue, who helped me tremendously when I took over in 2012. Harrison Nash kept his role as circulation manager until he fell ill, columnist Deanie Victor, reporter turned general manager Dianne Speights and columnist Frances Pinckney are a few still in the area.

Frances Pinckney

Pinckney wrote for the paper for more than 40 years. During that time she had several columns. His one stipulation was for his writers not to offend, especially not the advertisers.

And that is exactly what Pinckney did. She wrote a piece on an article written in a Catholic newspaper that she felt was bias. Being Catholic herself, her pastor wrote a letter to my father.

“I had to write a letter, kind of an apology. It didn’t turn out to be an apology, though,” Pinckney said.

“He called and told me, ‘Well, Frances,’ he said, ‘your letter was worse than the column.’”

As it turns out, her pastor was on the board of directors at Mass Brothers, a high-end retail store comparable to Dillard’s, and her letter caused a stir.

“I got laid off for a while. I had to lay low, and I understood…,” she said.

Reporter Winnie Foster, on the other hand, was not as understanding. My father told her to kill a story she’d been working on about how the city was not following federal law in their hiring practices.

According to Foster, “three white men in suits” visited my father and told him the city’s legal advertisement would be pulled if they went ahead with the story.

Foster refused to back down and quit.

The legacy continues

My father always had a menthol cigarette in his hand. Even when he was diagnosed with lung cancer, he continued to smoke. He passed away July 29, 2001, 11 days before his 74th birthday. His funeral was held at Mt. Zion Progressive Baptist Church where Rev. Louis Murphy Sr. tends his flock. His old friend Pastor Rainey officiated over the service.

He left behind to cherish his memory, his wife Ethel Johnson; daughters Wanda, Lyn and Sakia Johnson. Sons Bennie McCall and Cyrille Johnson; granddaughters Traci Mayes and Keirsten Johnson and grandson Tyrone Cleveland Johnson, Jr. Son Tyrone Cleveland Johnson, Sr. proceeded him in death.

My father also left behind a legacy of community empowerment and entrepreneurship. He was known not only for his business acumen but also for his generosity. He contributed regularly to scholarship funds, gave interest-free loans and many times he gave knowing he would never see a dime in return.

He often gave paper routes to youngsters and made it a stipulation that they helped buy their own school clothes. One such former paperboy is now Senator Darryl Rouson. My father influenced generations of people, and his legacy continues.

Please join us in honoring the legacy of Cleveland Johnson, Jr. while celebrating the 50th Anniversary of The Weekly Challenger newspaper. From stories of local heroes to legends and leaders within our community – we’ve made history together!

Due to Hurricane Irma, the legacy team members postponed the celebration until Oct. 27. It will still be held at the historic Coliseum. Tickets to the celebration are available to purchase directly on our website (www.theweeklychallenger.com), on the Sanderlin Center’s website (www.sanderlinfamilycenter.org) and locally at the Coliseum, Gallerie 909 and Kidz World Preschool.

$50 Per Person | $500 Table of 8 | Table Sponsorships are Available | Click Here to Purchase

For more information or to sponsor, contact Deborah Figgs-Sanders (727) 420-2819 or email us at Celebrate50@theweeklychallenger.com.

Not only do we invite you to take a walk through history with us, we’d like to continue making history together – a new narrative for the legacy of our community.

Cleveland Johnson with members of the

Orange Blossom Beautician Association