No one person can be a systemic issue; every member of the system contributes to its effectiveness or its dysfunction.

BY MICHAEL F. BROOM, Ph.D., Organization Development Psychologist

A key issue in making teams work is understanding them as human systems, a concept new to most leaders. A human system is any group of people who impact each other, such as teams, committees, families, clubs, neighbors, and friendships.

The importance of human systems lies in the fact that they take on a life and behaviors of their own, separate from the intentions and values of its members. In doing so, human systems tend to manage us rather than our managing them.

Think of those meetings we all complain so much about. The people in those meetings are typically well-intended and intelligent, yet their meetings are dysfunctional. This signals a human systems problem.

Our western culture’s emphasis on individuals makes it difficult to see human systems. This leads to individuals getting blamed for human system problems, which worsens the system problem.

The first step to working effectively with human systems is to see them. Look for what the system is consistently doing or not doing rather than what particular individuals are doing.

Typically, are ideas from several people generated and spawning new ideas? Is there laughter and fun while work is getting done? Or is there silence with only one or two people dominating the meeting? Are people constantly interrupted? Are zingers, conflict, and passive aggression normal behaviors?

Any behavior typical of a team member meeting is likely to be systemic. And if the behavior is inhibiting the team’s work, it must be remedied.

To see what a system is doing, notice what most team members are doing. Often, there is a focus on the leader of the team or some other dominant figure.

In the adjacent cartoon, that would be the guy with the beard who will be gossiped about after the meeting for being boring. However, the systemic dysfunction is that most of the system members are busy being silent in their boredom.

The leader is contributing too because he is not addressing the dysfunction either. Likewise, if you are a system member, notice what you’ve been doing while the dysfunction persists: that would be your contribution to the dysfunction.

Regardless, no one person can be a systemic issue; every member of the system is contributing to its effectiveness or its dysfunction.

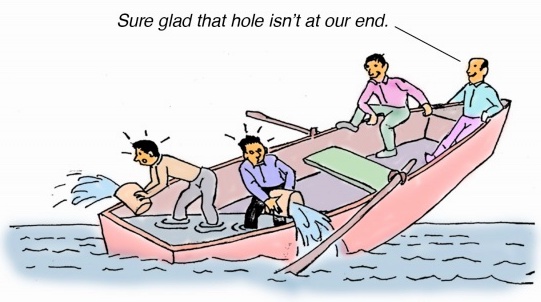

A more challenging example is the four guys in the troubled rowboat going nowhere. Most people see the problem as the two guys at the top disdainfully not helping the two guys bailing at the bottom.

As a systems problem, all four guys contribute to the boat going nowhere. The two guys up top are contributing by doing nothing to address the problem other than congratulating themselves.

The guys bailing may keep the boat from sinking, but it still isn’t going anywhere. Any bored folks at the meeting could speak up with an idea that could stimulate more conversation.

The same is true in the boat. Anyone could speak to the lack of communication, coordination, and collaboration needed to get things moving again.

Developing healthy human systems

Once we can identify human system dysfunctions, solutions are often easy to find. For example, any of the guys in the rowboat could point out that if one of the bailing guys moved to the middle to row while the other three bailed from both ends of the boat to keep the boat level, they could get moving.

Here are three ideas for creating positive synergy and resolving negative synergy in teams:

- Invite team members to engage fully in team discussions. This should include speaking up about team dysfunctions. In many organizations, there is a cultural and group norm to speak up about team dysfunctions only through complaints outside of team settings. Speaking up in the meeting is seen as risky, possibly offensive to the leader and career-limiting. Team leaders must be persistent in seeking input from all team members, listening well, and not taking silence as consent.

- Conduct checks during meetings about how well things are going and how to improve. At a minimum, leave time toward the end of team meetings for people to share their perceptions of how things are going.

- Assure that the work of teams is done collaboratively and decisions are made consensually with a premium placed on listening and engaging curiosity instead of judgment about divergent ideas. This creates the positive synergy that leaders are seeking.

Michael F. Broom, Ph.D., has been an organization development psychologist for 45 years. He consults with organizations of all types, including Google and Genentech, among others. He has taught at major universities, including Johns Hopkins and American. For more information, you can contact him at www.chumans.com or michael@chumans.com.

Michael F. Broom, Ph.D., has been an organization development psychologist for 45 years. He consults with organizations of all types, including Google and Genentech, among others. He has taught at major universities, including Johns Hopkins and American. For more information, you can contact him at www.chumans.com or michael@chumans.com.