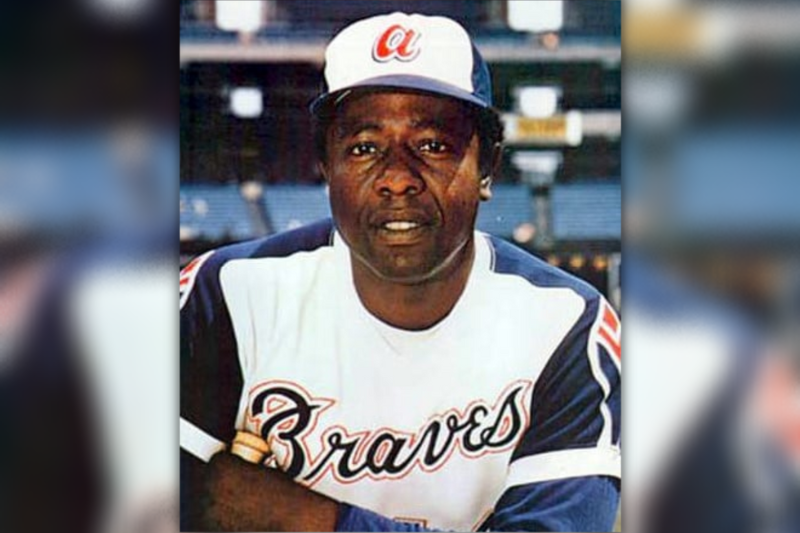

Since his retirement, Hank Aaron has held front-office roles with the Atlanta Braves. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

Jackie Robinson blazed the trail for an entire race when he first trotted out onto Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947, but that was merely the first shot fired in the war against baseball’s longstanding racial prejudices. In time, many other talented black players would follow this same path that turned out to be a minefield of suspicion, suppression, and segregation.

The Major League ball clubs in those days called Northern and Midwestern cities such as New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago and St. Louis home. Most of them descended upon warmer climates every March to work out the kinks and get ready for the season. That meant spring training games in the Florida sunshine — where Jim Crow called home.

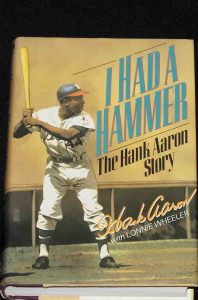

In his 1991 autobiography “I Had a Hammer,” Hank Aaron noted that he considered himself a second-generation black ballplayer by the time he broke into the majors in 1954 with the Milwaukee Braves. By 1960, all the teams had integrated, and pioneers such as Robinson, Roy Campanella, Joe Black, Larry Doby and Monte Irvin were out of the game.

In his 1991 autobiography “I Had a Hammer,” Hank Aaron noted that he considered himself a second-generation black ballplayer by the time he broke into the majors in 1954 with the Milwaukee Braves. By 1960, all the teams had integrated, and pioneers such as Robinson, Roy Campanella, Joe Black, Larry Doby and Monte Irvin were out of the game.

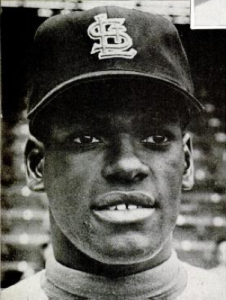

But players like Aaron, Willie McCovey, Bill White, Bob Gibson and Lou Brock were swinging and hurling and speeding their way onto the big-time baseball diamonds. And though they may have been given a chance to play alongside white men, segregation made certain that the playing field was the only place where that was tolerated.

Black ballplayers were forced to stay in lodgings apart from their white counterparts, which was par for the course for the many who hailed from the South.

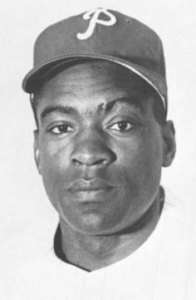

Bill White became the president of the National League in 1989, the first African American to hold such a high-ranking executive position.

“When we were in Bradenton,” Aaron writes in his book, “the white players stayed at the big, pink Manatee River Hotel and the black players lived in an apartment over a garage owned by a black schoolteacher named Lulu Gibson.”

The black Braves players had to crowd into two bedrooms and a hallway, but the home-cooked meals couldn’t be beaten, Aaron remembered.

“We’d wake up every morning to bacon and biscuits and gravy,” he said.

Small consolation indeed. Aaron wrote that one year, as soon as they arrived in Bradenton, the Ku Klux Klan marched down Ninth Street, where Mrs. Gibson’s house sat. He didn’t know if that demonstration was for the players’ benefit, but it was a not-so-subtle reminder that they were very much in a southern town.

The ballpark at Bradenton back then still had separate sections for whites and “coloreds.” Aaron’s young wife, Barbara, even refused to attend the games because she refused to sit apart from the white wives.

One day after a spring training game, future home run king Aaron went with some teammates to a Dairy Queen across the street from the ballpark to get some refreshments. When it was his turn to step up to the window and order, the lady inside told him to go around back to the colored window.

About 30 years after that incident, Aaron received a letter from a man who had been living in Bradenton then, and he wrote Aaron that he and his wife were good friends with the couple that ran that same Dairy Queen, and his wife worked for them on occasion. It was the man’s wife that had to serve Aaron at the colored window. It bothered her so much that she broke off the friendship with the other couple, “quit the job, and went home and cried for a couple of days.”

As Aaron hailed from Mobile, Ala., he was well familiar with the white southern mentality and rigid boundaries concerning African Americans; yet, he mused that in some ways, Bradenton was worse than Mobile. The newspapers in Florida wouldn’t even print pictures of the black players.

The black players were also advised not to drive cars at night, and they never knew what might happen if they tried to hail a cab. At times, white drivers would refuse to take them anywhere, and at other times, white police officers actually stopped cabs an ordered the black players to get out, which put them at risk of being arrested for just standing on the street.

Tony Gonzalez was almost arrested in Tampa for standing outside of a movie theater while his teammate when in for ice cream.

Tony Gonzalez, while playing for the Cincinnati Reds in Tampa, recalled a time when he went with one of his “white Spanish teammates” into a white movie house to buy ice cream. Gonzalez, because of his color, couldn’t go inside and had to wait for his teammate outside.

“While I was waiting,” he remembered, “a couple of policemen walked up and arrested me. I couldn’t speak a word of English, but they put me in a police car and started to take me away. I was making like I was hitting a ball so they could understand I was a baseball player. So they took me back to the camp and said, ‘You stay here.’”

First baseman Bill White broke into the majors in the 1950s and also got to know very well what springtime in Florida meant to players of color. From 1959-65, he was playing for the St. Louis Cardinals, who played their pre-season games in St. Pete.

“The St. Petersburg Yacht Club used to invite eight or nine Cardinal players to a breakfast every spring,” White said, “and one day, I made the comment to Joe Reichler, who was a baseball writer for UPI, that none of the black players were ever invited.”

Reichler then wrote an article about the segregation in spring training, and that was something White hoped would get the ball rolling toward integration. Sure enough, the exclusive club soon after broke with its longstanding tradition — sort of.

“After the article, the Yacht Club invited me to breakfast at something like one in the morning,” White recalled. “I told them, ‘thank you, that was a little early for me.’”

Yet that article was potent enough to put the pressure on the St. Louis ball club to move toward integration. The upshot was that the Cards were the first team to do something about the problem of separate quarters for players.

“Their solution was to segregate everybody, not just the black players,” White said. They leased a motel in St. Petersburg and just took the whole thing over.”

White ultimately rose above the bigotry in baseball as he went on to become the president of the National League in 1989, the first African American to hold such a high-ranking executive position.

With the Cardinals’ decision to house all of their players together, black ballplayers on other teams–including Aaron on the Braves–wanted the same treatment.

Aaron recalled the time when the vice president of the Braves Birdie Tebbetts called him into his office and asked the slugger if he was happy with the way things were.

“I said, ‘Hell, no, I’m not happy,’” Aaron wrote in his book. “‘It’s about time you all realized that we’re a team and we need to stay together.’”

And though the Braves had been saying that they would move toward integrating the players’ housing situation, nothing got done. The management claimed that it was hard to find a hotel to go along with this, as they all stuck together when it came to segregation. If one of them gave in, the other establishments would have no choice but to follow suit.

A solution presented itself when a man offered his Twilight Motel in Palmetto, next door to Bradenton. Since his property wasn’t situated in the city, he was willing to take on the whole team, black and white players alike. Aaron noted that the white players were none too thrilled about moving out of the sprawling Manatee River Hotel and into a “two-bit motel” in the next town.

“And for that matter,” Aaron said, “the black players knew we’d be leaving behind some first-rate chicken and biscuits — but it had to be done.”

As big a step as this was on the path to integration and acceptance, at least one African American didn’t like the change. When Aaron ran into Lulu Gibson a few weeks after the black players moved out, “she was crushed,” Aaron noted. Gibson felt that Aaron himself was behind the move, and it made her feel as though he’d walked out on her. Didn’t he love her? She asked him? Didn’t he like being in her home?

“I said, ‘Mrs. Gibson, that’s not it at all,’” Aaron remembered. “‘I love your home, but it’s time now for baseball to understand that we have to have a choice of where we want to stay, and you have to understand that, too. It’s very important that we make that statement.’”

Source: “I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story” by Hank Aaron with Lonnie Wheeler, HarperCollins Publishers, 1991.

To reach Frank Drouzas, email fdrouzas@theweeklychallenger.com