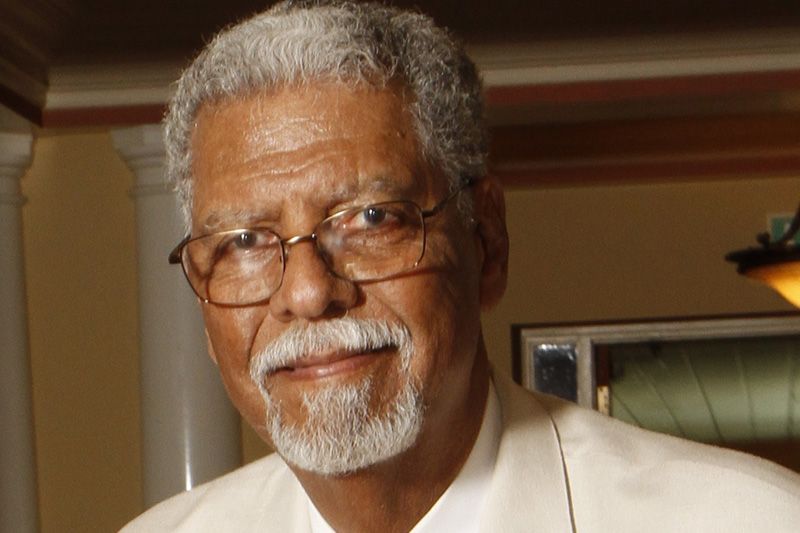

Adman William “Bill” Blackshear, one of the cornerstones upon which The Weekly Challenger was built, passed away Sunday, March 21. Photo courtesy of Pop Lancaster.

WOODBRIDGE, Va. — William “Bill” Blackshear, one of the cornerstones upon which The Weekly Challenger was built, passed away Sunday, March 21.

From army veteran to GE Plant Weapons specialist, from history-making public official to groundbreaking trailblazer and salesperson “extraordinaire” of Pinellas County’s oldest African-American newspaper, Mr. Blackshear filled a tremendous void while living a public life to its fullest.

Born in Marianna, Fla., on June 1, 1935, to William Sr. and Julia Dennis, née Spires, he was raised by his mother and his grandmother, Anne Spires, until adulthood. The family moved to Safety Harbor in 1947, where Mr. Blackshear spent his teenage years and where he also met his wife-to-be, Ms. Betty Booze, in Clearwater.

The two married in 1953, and soon the babies started coming, six in all. Mr. Blackshear served in the United States Army for six years, two years in active duty and four in the reserves. He was honorably discharged in 1962.

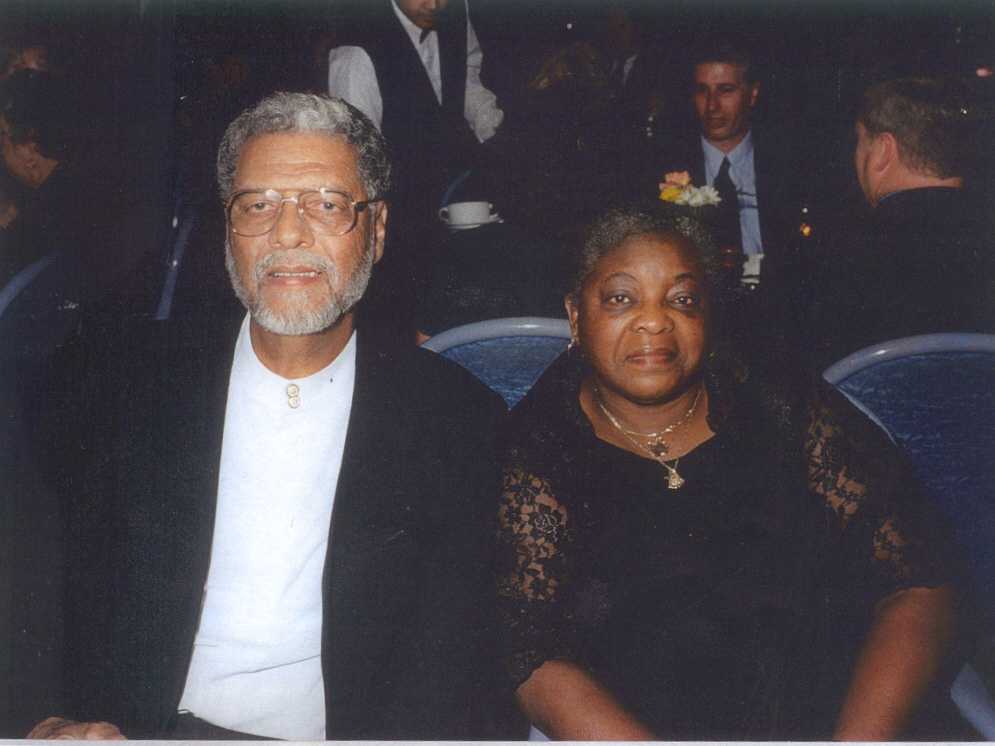

William Blackshear and his wife Betty, who passed away in 2018 | Photo courtesy of the Blackshear family.

Mr. Blackshear worked for General Electric’s Pinellas Peninsula Plant in advanced production on the Atomic Energy Commission contract. He then lent his talents and commitment to public service, first serving as president of the Lincoln Nursery Association, then president of the Lincoln School PTA, and chairman of the Lincoln Highland Home Improvement Committee.

In 1964, then 29-years-old, Mr. Blackshear achieved a stunning political victory during the days of Jim Crow Pinellas County. He defeated three white candidates for a Safety Harbor city commission seat. The day after the election, a St. Petersburg Times article headline read: “Negro Wins City Election.” Mr. Blackshear was the first African American to run for office in Safety Harbor and Pinellas County.

According to Gloria Gilghrest at the Pinellas County African History Museum, Mr. Blackshear was also the first Black person elected to public office in Florida since the end of Reconstruction in 1877.

Seen here in 2008, William Blackshear was honored by the City of Safety Harbor as the Grand Marshal of the Safety Harbor Christmas Parade. Photo courtesy of the Blackshear family.

Spoken with eloquence and humility, Mr. Blackshear was quoted at the time as saying, “I don’t feel I have won a victory over anyone. I have been placed in a position of dignity and respect by the citizens, and I will try faithfully to measure up to the dignity and trust of this position.”

In 1967, Mr. Blackshear teamed up with Cleveland Johnson, Jr. to start The Weekly Challenger. It was the beginning of a partnership that would last 34 years. He and Mr. Johnson entirely created an advertising-supported news vehicle for the African-American communities of Tampa Bay.

Throughout the years, both Mr. Johnson and Mr. Blackshear helped other Black newspapers, financing their efforts to get them off the ground. Mr. Blackshear would volunteer days on end, working for and training the upstarts as a non-paid employee.

As an advertising guru, Mr. Blackshear chased after larger advertisers, veering away from the traditional Black newspaper advertisers: mom-and-pop stores. This approach was instantly successful. He sought and earned Publix advertising, and the supermarket has been The Challenger’s most loyal major advertiser since 1968.

With Mr. Blackshear at the helm, new revenue streams poured in from other grocery and department stores such as J.C. Penny, enabling The Challenger to transition from a tabloid to a broadsheet format in 1970.

Front, Cleveland Johnson, Jr, and William Blackshear putting together an edition of The Weekly Challenger, circa 1976.

In 1977, Mr. Blackshear founded the Southeast Black Publishers Association. Its initial purpose was to be a vehicle for sharing successes, contacts and resources. They even envisioned creating a statewide agency so that all of the papers in the network could be part of joint buys. He became the first president, serving for five years.

In 1991, Mr. Blackshear started up a regional paper, The TriCounty Challenger, focusing on Marion, Citrus and Hernando counties. The front page was different, along with some inside pages. It was merged with the main paper five years later, and both The TriCounty and The Challenger’s names shared the front page until late 2001.

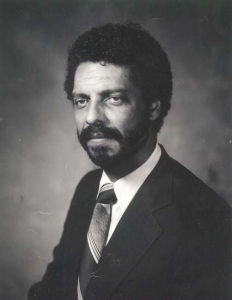

In a 2002 interview before his retirement, he shared his experience working for a community newspaper for more than 30 years.

“We [Mr. Johnson] had an extremely worthwhile partnership, and what made it so was that we never lost sight of what we came together for in the 60s. We recognized, too, that we saw ourselves as being bit players on a very large scale. Both of us tended to shun the spotlight.”

On Jan. 31, 2002, Mr. Blackshear quietly rode off into the next phase of his life, leaving the community with these parting words: “I am grateful for having the opportunity to make a difference in the lives of many folk [sic], of being a part of a program that was geared to the development of the Black community as a whole.”

He and his wife settled into retirement in Dunnellon, where he volunteered at a VA hospital in Gainesville and had planned to spend lazy days with a fishing pole in his hand, but his wife became ill, and he dedicated himself to her care until she passed in Feb. of 2018.

He eventually moved to Virginia last December to live with his family and peacefully passed away in the hospital on March 21.

William Blackshear retired from The Weekly Challenger after 34 years of service to the community in 2002. Photo courtesy of the Blackshear family.

Blackshear was a dedicated and loving family man who adored his wife and their marriage. He leaves behind six children: Bruce Blackshear (Largo), Angelia Rodriguez and husband Joseph (Orlando), Edwina Blackshear (Tarpon Springs), Jeffery Blackshear (Bradford County, Fla.), Sylvia Cunningham (Ruskin), and Jacqueline Williams and husband Ret. Col. Harry B. Williams (Woodbridge, Va.); 21 grandchildren, 43 great-grandchildren, six great-great-grandchildren, sister-in-law Catherine Sumter (New York City), and a host of nieces, nephews, other family members, and friends to cherish his memory.

Due to the pandemic and the ongoing CDC restrictions on gatherings, the family has decided to forego funeral services and will host a Celebration of Life service in honor of Mr. William Blackshear at a time to be determined in 2022.

Some information obtained in this article was taken from a 2002 Weekly Challenger feature by Barry McIntosh.