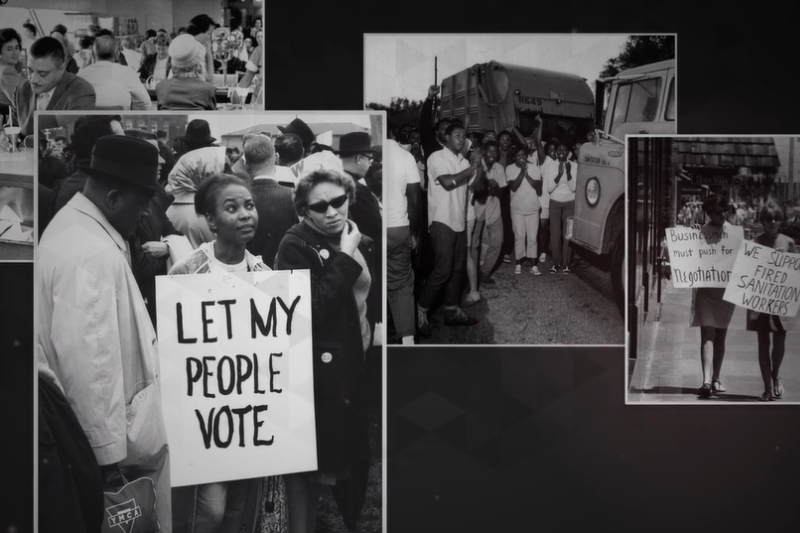

It’s important that we recognize those who came before us with a vision of a better, fairer society and the courage to challenge the status quo to achieve it.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburgand the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, Inc. (AAHA)presented the enlightening documentary “A Visual History of Civil Rights & Social Change in Pinellas County,” which delves into such topics as the history of the first Black settlers, establishment of Black neighborhoods and businesses, segregation, integration and voting rights.

Narrated in part by Gwendolyn Reese, president of the AAHA, the documentary serves as an entry point for education understanding and further exploration. The stories of how our community came to be are vital because they continue to shape who we are today. Without knowledge of where we’ve been, it’s challenging to move forward in a way that prioritizes equity for all.

Sports and desegregation

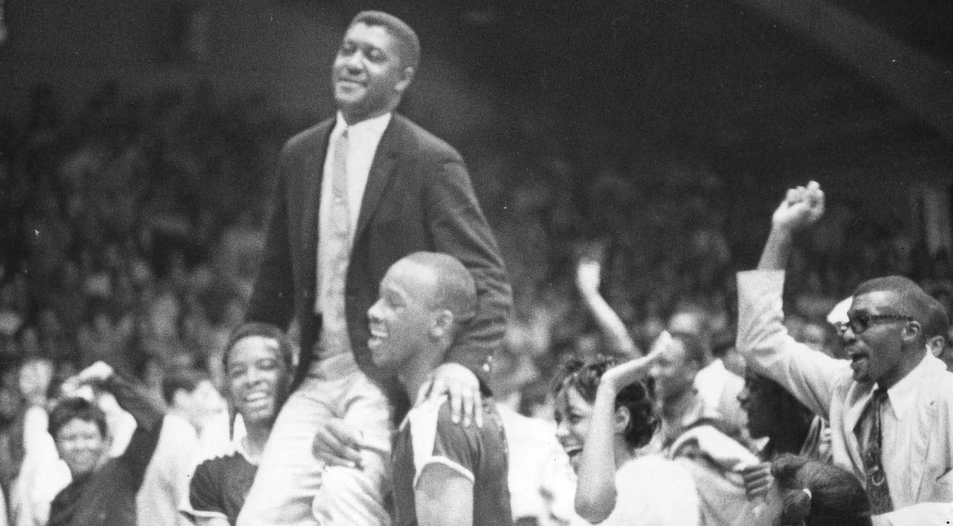

Communities have long rallied around sports, and some believe that competitive athletic contests helped move us toward better race relations in the late 1960s and 1970s. On Dec. 20, 1966, Gibbs High School basketball coach Freddie Dyles responded to a question about what he wished for Christmas by saying, “An even break from area basketball officials!”

Reese said this was due to the unfair calls made by predominantly white officials against his team.

All-black Gibbs played all-white Clearwater in the final game of a holiday tournament at the Bayfront Center to a crowd of about 7,500 spectators on Dec. 30, 1966.

Gibbs defeated Pensacola Escambia and Boca Ciega on the way to the finals. During the game against Boca Ciega, a thief snuck into the Gibbs Gladiators’ dressing room at halftime, stealing money, class rings and other valuables.

Even with unfair calls and the theft of personal belongings, Gibbs went on to defeat Clearwater 70-66 in front of 7,500 fans in what was called “the greatest show on earth.”

“It was the largest crowd to ever witness a Florida high school basketball game, and the fans were not disappointed,” Reese said. “They saw basketball at its best!”

The year 1966 was historic as Gibbs High won the Florida Interscholastic Athletic Association state championship and advanced to the national tournament in Montgomery, Ala., where they won two games and lost one.

School resegregation

One of the consequences of racially discriminatory mortgage lending, the practice known as redlining, is that American neighborhoods are deeply segregated by race, as are the schools that serve them. From the outset, school desegregation was widely and bitterly opposed.

Court-ordered busing brought turmoil in 1971. From the outset, school desegregation was widely and bitterly opposed.

Court-ordered busing brought turmoil in 1971, but it also created the opportunity for friendships and a deeper understanding between races among students and teammates of that first generation of integration. Pinellas County schools and sports teams have begun to resegregate into neighborhood groups since a judge ordered the end of busing in 2000.

Equity for all

Racism and racial discrimination are the most common obstacles to good health and good quality of life for residents in Pinellas County. Other types of discrimination such as gender, sexual expression, disability, age, and income also inflict harm and limit the potential of people who experience it. Our local history of civil rights leadership includes champions of these marginalized groups.

Disability Rights

Currently, one in eight Americans experience a disability that affects mobility, and millions more will face a short-term disability affecting mobility at some point in their lives. People experiencing disabilities often struggle to negotiate dangerous and inconvenient obstacles in the built environment.

George Locascio, stricken with polio in 1945, spent more than 30 years using a wheelchair or crutches, Reese said, and knew what it was like to live with a disability. His best-known fight was in 1988, when he battled the city and filed a lawsuit over inadequate seating for the disabled in what was then the Florida Suncoast Dome.

In 1988, George Locascio battled the city and filed a lawsuit over inadequate seating for the disabled in what was then the Florida Suncoast Dome, now knowns as Tropicana Field.

The stadium, now known as Tropicana Field, only had 137 wheelchair spaces relegated to one floor. Federal guidelines required a stadium the size of the Dome to have at least 440 spaces in various areas throughout the facility.

“Locascio saw the Dome as another example of society’s insensitivity to the disabled,” Reese said.

The lawsuit was settled in 1990, resulting in additional wheelchair seating and improvements to the restroom and concession areas. In 2006 at the age of 80, Locascio was awarded a lifetime achievement award from Abilities, Inc. He died on Dec. 5, 2009, at the age of 83.

The Americans with Disabilities Act was first introduced in congress in 1988 and was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush on July 26, 1990. Long before that, in 1972, the City of St. Petersburg established the Committee to Advocate for Persons with Impairments. By 2003, the city had installed an estimated 4,500 curb cuts to help people move easily from sidewalk to street. Improving access to wheelchairs has improved the urban environment for all.

Reese explained that the Disability Rights Movement started when people with disabilities and parents of children with disabilities began to challenge the system. It took years of organizing, filing lawsuits, testifying on the state and federal level, mailing, phoning, letter writing and sometimes even getting arrested. The Disability Rights Movement, like so many others, adopted many of the strategies of the Civil Rights Movement.

A hidden minority

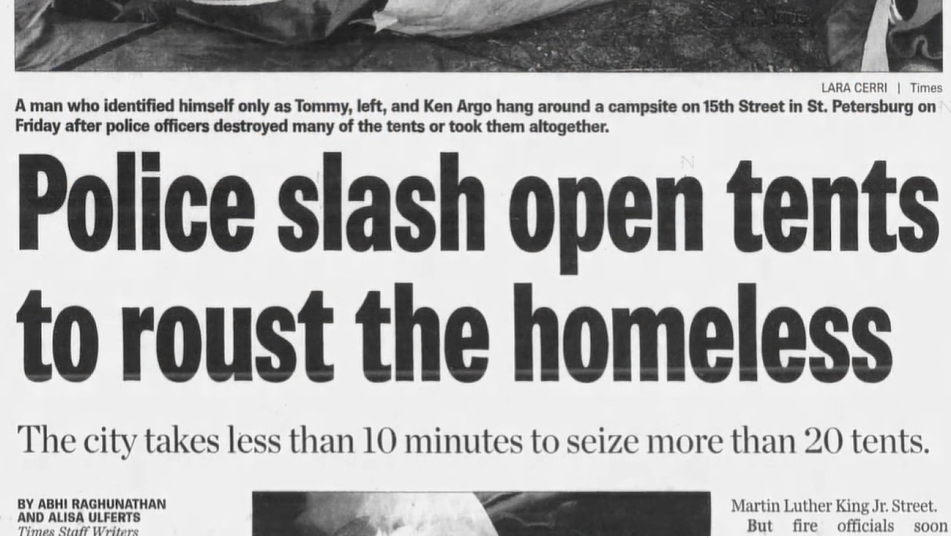

Homeless people are a hidden and often ignored minority in our society. Far from sharing an equity, they live on the streets, in cars, under bridges, empty buildings, and within patches of dense brush on interstate rights of way. In 2007, St. Petersburg police slashed tents belonging to the homeless, citing their conditions as fire hazards.

After that episode, a homeless advocacy group called St. Petersburg one of the nation’s meanest cities. Also, in 2007, Catholic charities and governmental groups founded Pinellas Hope, a temporary shelter for people with no place to live.

It offers tents, apartments, cottages, meals, and counseling to help people become self-sufficient and enjoy a greater share of social equity. It has taken in tens of thousands of people, about half of whom move on to stable housing. In 2019, on a given night in Florida, 28,328 people experienced homelessness.

“An annual account turns up thousands of homeless adults, children, and families who don’t have the money to pay market rents, secure subsidized housing, or even access the limited number of temporary shelters or beds,” Reese said.

The current affordable housing crisis in Pinellas County does not bode well for the prospect of housing the homeless. Countywide housing research revealed that there’d been a sharp decrease in new units of affordable housing, down from 401 new units and 2012 to only 86 units in 2016.

It is estimated that there is a deficit of almost 20,000 housing units for extremely low-income households countywide, and that was before the COVID-19 crisis brought housing, security, and homelessness to the doorsteps of thousands of working poor and middle-class families.

“This situation has become more acute due to COVID-19,” Reese noted. “The affordable and accessible housing crisis in Pinellas County must be a focus for health equity advocates as we confront this unacceptable situation in our community.”

Advances for the LGBTQ+ community

The Stonewall uprising began on June 28, 1969, in response to a New York City police raid of the Stonewall Inn, a gay club in Greenwich Village. Fighting the oppression and taking cues from the Civil Rights Movement, members of the LGBTQ+ community led a series of protests and demonstrations that lasted six days, including a protest march with more than 2,000 people.

Largely credited as a turning point in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights, the Stonewall uprising inspired more organized activism for LGBTQ+ equality and launched the modern-day Pride Movement.

Marcia P. Johnson was a Black gay liberation activist and self-identified drag queen. Known as an outspoken advocate for gay rights, Johnson was one of the prominent figures in the Stonewall uprising.

Marcia P. Johnson was a Black gay liberation activist and self-identified drag queen. Known as an outspoken advocate for gay rights, Johnson was one of the prominent figures in the Stonewall uprising. Johnson disappeared on the eve of the Gay Pride Parade in July 1992, and her body later surfaced in the Hudson River. Law enforcement ruled it a suicide, but her friends believe she was murdered. Her murder remains unsolved.

In 1977, eight years after the Stonewall episode in New York City that launched the Pride Movement, Florida citrus spokeswoman Anita Bryant waged an ongoing, nationally publicized verbal war with gay people, Reese said. In St. Petersburg, police routinely harassed and arrested gay men in parks and other public spaces for suspected homosexual activity.

“As recently as the early 1980s, St. Petersburg undercover police routinely arrested gay men,” she said.

In 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down laws governing homosexuality, making it legal in all 50 states. In 2015, the court struck down the last state law banning same-sex marriage, making marriage equality the law of the land.

St. Petersburg hosts the largest annual Pride Parade and celebration in the Southeast, and it’s consistently named as one of the most LGBTQ+-friendly cities in the region.

In the summer of 2020, the Supreme Court ruled that federal sex discrimination protection extended to LGBTQ+ people in the workplace. It protects employees from being terminated simply because of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

St. Petersburg hosts the largest annual Pride Parade and celebration in the Southeast, and it’s consistently named as one of the most LGBTQ+-friendly cities in the region, Reese said. The parade and celebration were founded in 2003 by a group that included Mark Bias, Carrie West and Brian Longstreth. Former Mayor Rick Kriseman, then on the city council, was the only council member to sign it.

Despite the progress made, LGBTQ+ people are not protected from housing discrimination in most states, including Florida, nor is there federal or Florida law protecting LGBTQ+ employees from discrimination.

Add to the story

We hope you have been informed and inspired by these stories of people working to make Pinellas County and our world a more just and equitable place. It’s important that we recognize those who came before us with a vision of a better, fairer society and the courage to challenge the status quo to achieve it.

Their work can provide guidance and inspiration for the new chapters of change and progress that are being written by today’s equity advocates. There are many more accomplished people and rich histories that are not included here. But the story continues, and you can help shape it.

Do you have a story of social change or social movement that you are engaged in or that moves you? The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg is collecting ideas and stories and would love to hear from you. Contact them at History@Healthystpete.foundation.

Click here to watch the documentary.