Black men are the hardest hit by these overdose disparities. There were 54.1 fatal drug overdoses for every 100,000 Black men in the United States in 2020.

BY YOLANDA GOODLOE COWART, Staff Writer

When COVID-19 exploded onto the scene in 2020, many people took it seriously, knowing the pandemic would be unlike anything they had ever experienced. With COVID-19, the health of the public was under attack, and many were reasonably worried. But what we could not predict is the many ways besides our health that COVID-19 would impact the Black community.

The pandemic has pushed the economy to the edge of a global recession, caused the Great Resignation in the corporate world, intensified the mental health issues that many were facing and has driven many companies to bankruptcy. Studies show that it has caused a meteoric rise in drug overdose deaths.

The federal government released new provisional data, estimating that nearly 108,000 people died from drug overdose between January and December 2021. In 2020, over 6,150 people died from overdoses involving Fentanyl and Fentanyl analogs in Florida.

According to Farida Ahmad, a research scientist with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics, this is almost a 15 percent increase in deaths recorded in 2020.

In 2020, almost 92,000 people lost their lives to drug overdose; this was a record-breaking increase of 30 percent from 2019 and a 75 percent increase from 2015 to 2020. Sadly, the Black community makes up the largest demographic of lives lost within these statistics.

The current rate of drug overdose deaths in recent years

The drug overdose death rate increased by 44 percent for Black people in 2020. In fact, Black people and non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islanders saw the most significant percentage increases.

Black men are the hardest hit by these overdose disparities. There were 54.1 fatal drug overdoses for every 100,000 Black men in the United States in 2020. In 2015, Black men were less likely than white men, Native Americans or Alaska Native men to die from an overdose.

But with an increase of 213 percent between 2015 and 2020, Black men saw the fastest growth in drug overdose deaths. In fact, Black men overtook their white counterparts in drug overdoses and are now the demographic most likely to die from it, along with indigenous populations. What’s worse is that even with these alarming statistics, some age groups within this demographic are witnessing higher death rates than the rest.

Statistics in 2020 showed that Black men 65 years and older overdosed at seven times the overdose death rate for white men in the same age group. Even more troubling, young Black people between the ages of 15 to 24 saw an increase of 86 percent in overdose death rates. With historical data showing that women are less likely than men to die from a drug overdose, one can infer that men make up most of this distressing percentage.

What is causing the increase in drug overdose deaths?

The past two years have been challenging for most of our population is an overstatement. The pandemic severely negatively impacted our mental health. Some people have been able to power through the trauma, while others chose to lean on the mental health resources available. Unfortunately, some engaged in harmful coping mechanisms, like illicit drug use, to help them deal with the relentless stressors of the times. This has naturally led to an increase in drug overdose deaths.

There are multiple reasons for this sharp increase, but at the center of the cause are income inequality, the inequities in the healthcare system and the lack of adequate mental health resources in the Black community.

The rate of drug overdose deaths rose across the board regarding sex, age, and race during this period. As a group, Black men saw the most significant increases in 2020, 2021, and likely 2022. There are multiple reasons for this sharp increase, but at the center of the cause are income inequality, the inequities in the healthcare system and the lack of adequate mental health resources in the Black community.

The illicit drugs available now are far more toxic than before. Drug cartels have mixed illegally manufactured Fentanyl with many drugs sold on the streets. Fentanyl is 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times stronger than heroin. The addition of Fentanyl has primarily caused the rise in overdose deaths.

Statistics from the CDC show that overdoses involving drugs like Fentanyl rose by six times between 2015 and 2020 back this up. Essentially, street drugs are more likely now to cause an overdose or result in death.

Some could not refill their prescriptions for pain medication and delved into illicit drug use as a method for pain management. Others could not handle the lockdown and experimented with drugs to manage the mental effects of isolation.

In addition, the DEA has taken a hard stance with pharmacies that distribute buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder. Studies have shown that buprenorphine reduces the risk of overdose by half and doubles the chance of long-term recovery. Because buprenorphine is also an opioid, which can be misused, the DEA is focused on limiting its diversion to the streets.

Health inequities, like unequal access to substance use treatment and treatment biases, are prevalent in racial and ethnic minority groups. Black people frequently lack access to healthcare and drug treatment.

According to Mbabazi Kariisa, Ph.D., the principal author of “Vital Signs: Drug Overdose Deaths, by Selected Sociodemographic and Social Determinants of Health Characteristics — 25 States and the District of Columbia, 2019–2020,” while treatment for substance abuse was limited among people who died from an overdose, it was especially so among Black people.

Evidence of previous substance use treatment was lowest for Black decedents (8.3 percent). As the level of income inequality increased, overdose rates increased, particularly among Black people.

Income inequality also factored into the rate of drug overdose deaths. In counties with the highest income inequalities, there are high rates of overdose deaths. This is especially true among racial and ethnic minority groups. Income inequality, as discussed by Kariisa, “can lead to lack of stable housing, reliable transportation, and health insurance, making it even more difficult for people to access treatment and other support services.”

There are many other reasons for the rapid increase in drug overdose deaths within the Black community. Many of these reasons circle a general lack of access to necessary resources to prevent drug use or treat substance abuse.

Possible solutions to the increase in drug overdose deaths

The Stanford-Lancet Commission predicts that with no intervention, 1,220,000 fatal opioid overdoses will occur in the U.S. between 2020 and 2029. If things remain the way they are, many of these deaths will be Black men.

Drug overdose death rate among Black men in the U.S. more than tripled between 2015 and 2020.

Luckily, some interventions can prevent these dire predictions from coming true. They include broad public health campaigns targeting Black communities to highlight the dangers of opioid misuse. Our community needs to be informed of the increased risks of illicit drug use and the available resources.

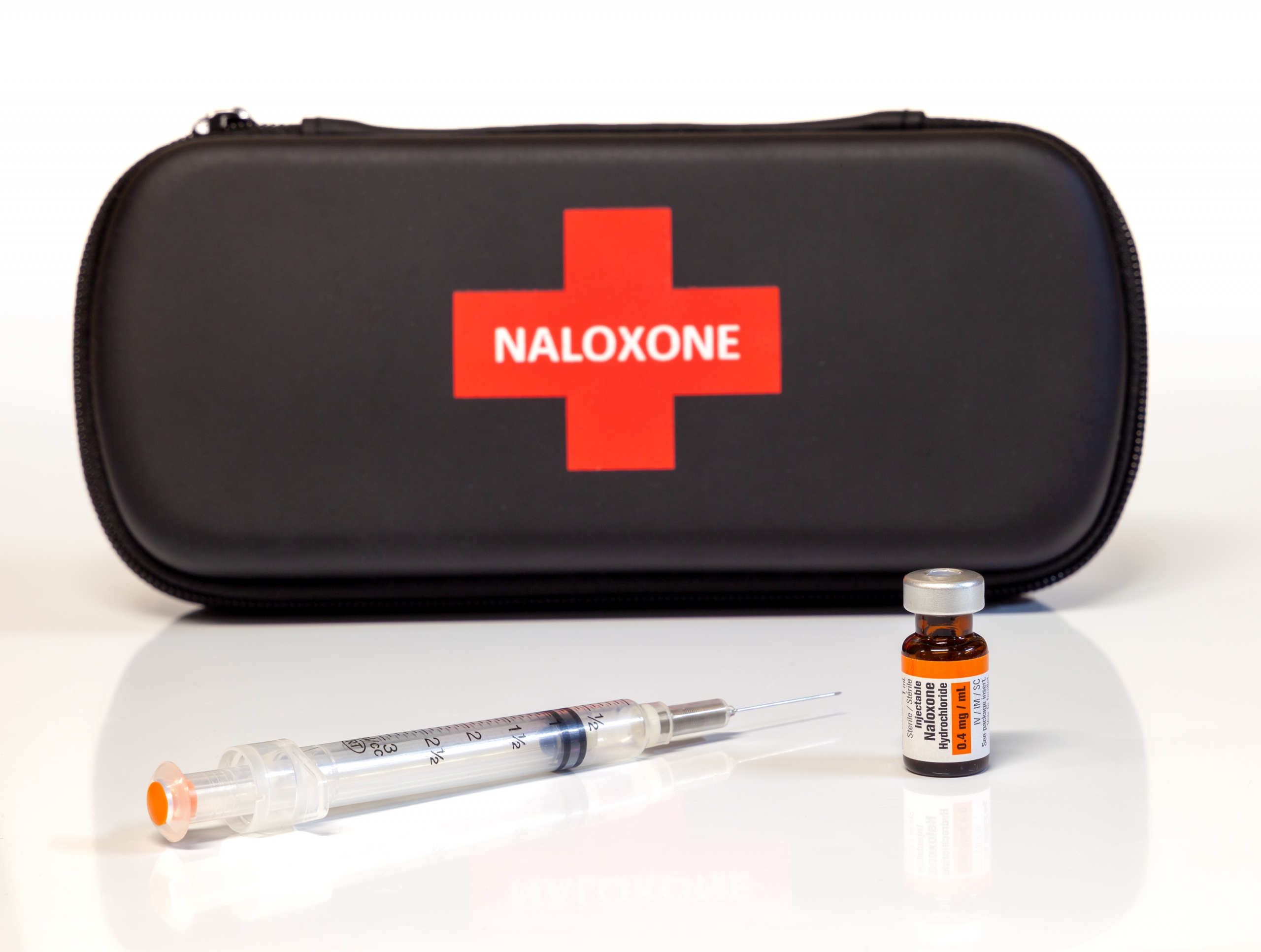

We also need provisions for accessible community-based resources for harm reduction and addiction treatment. This includes increased availability of substance abuse treatment services and harm reduction measures, such as Naloxone, test strips that allow users to determine if the drug they’re using contains Fentanyl and referrals to substance disorder treatment services.

The federal government could also consider removing the ban on federal funding for syringes. Syringe service programs are good opportunities to reach people who inject drugs and provide them with overdose prevention education and links to mental health resources and drug treatment options.

Providing structural support, such as housing, transportation assistance, and childcare, can also help reduce and remove any barriers that drug users may face when seeking treatment and staying in recovery.

Changing the forecast

Efforts need to be made to reduce the stigma associated with drug addiction through education and sensitization. A recent report showed a surprising increase in overdose death rates in areas with more treatment services and mental health care providers.

There is a need for accessible community-based resources for harm reduction and addiction treatment. This includes increased availability of substance abuse treatment services and harm reduction measures such as Naloxone.

In 2020, in areas with at least one opioid treatment program, the death rate among Native Americans, Alaska Natives and African Americans was more than twice that of places without such services. It is believed that the fear of being stigmatized and a general mistrust of the healthcare system are causing this spike, even though preventative services are available. Outreach and education programs can help reduce these challenges in our community.

Recently, the Biden Administration announced its plans to address the rising number of overdose deaths, which includes increasing access to harm reduction methods like clean needles, Fentanyl test strips, and Naloxone. Some states are even taking steps beyond the administration’s harm reduction plans. Massachusetts, for example, is distributing crack pipes to limit transmission of infections and is considering legislation that allows supervised drug use to prevent overdoses.

While the current predictions are dismal and Black men are likely to be the ones most affected by overdose disparities, there is hope because solutions are available to prevent the massive loss of lives. Creative proactive programs can go a long way to encourage people to seek treatment and commit to their lifelong recovery.

If a concentrated effort is made to treat substance abuse and reduce overdose, our community stands a chance in this war against drugs and can begin to save more Black men’s lives.

Yolanda Goodloe Cowart is an author, small business champion, victim rights advocate, civil rights activist, and human rights defender in St. Petersburg-Clearwater.