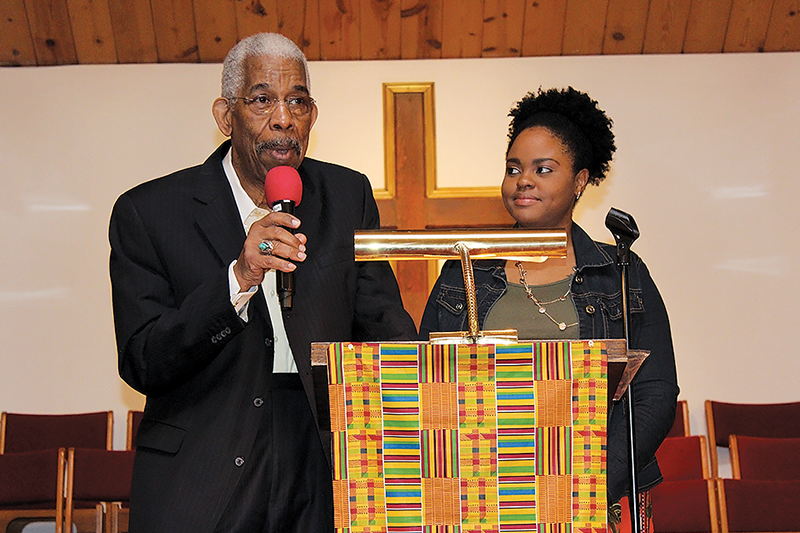

Ernest Patton, Jr. and Rev. Jana Hall-Perkins, senior pastor of McCabe United Methodist Church

BY HOLLY KESTENIS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – Renowned civil rights legend Ernest Patton, Jr. visited McCabe United Methodist Church last month to tell his story of freedom riding during the Civil Rights Movement.

Known as “Rip” to most of his friends and colleagues, Patton is a renowned community leader who spends time regularly speaking to groups all around the country. He enjoys telling his personal story and feels he is shining light on the past so that younger generations will understand the vital work the foot soldiers of the Civil Rights Movement did in order for African Americans to gain rights.

Patton spoke to the full church about the sacrifices he made, putting his personal interests as a young boy, such as music, to fight for racial equality. In 1960, he joined the Nashville branch of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), what was then a new organization.

Growing up, Patton had lived in a black community. All but one white family had moved out. So, nine-year-old Patton befriended the nine-year-old white boy still in the neighborhood, and they soon became playmates.

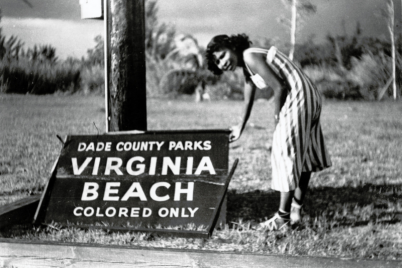

He heard how great the movie theater in downtown Nashville was from his friend and begged his mom to take him. When she did, Patton tried to walk right up to the front entrance like his white friend. He discovered quickly that blacks were to cross the street and head in through a side entrance. He learned that day about segregation.

“That young man really never forgot it,” said Patton, referring to himself. “When I think about it, it was like planting a bud. You plant something and then later on it’s going to flourish.”

When the opportunity arose, Patton participated in the nonviolent workshops he learned about usually by word of mouth or telephone. That’s where he met now Congressman John Lewis–then a student—and now one of Patton’s closest friends.

Dr. Martin Luther King had convinced Lewis to, “Forego your education and come South,” so he had. The workshops consisted of the teachings of Gandhi and how to protect themselves during sit-ins.

From the fall of 1959 to Feb. 13, 1960, they trained. On Feb. 13, some 124 volunteers went downtown to three stores and had an unannounced sit-in. The papers didn’t know about it, nor did the local television and radio stations.

By the following week, 200 students volunteered to go down to the stores, and by the end of the month, they had planned to hit all the stores along Nashville’s Fifth Avenue. Patton and other activists made progress, as they successfully integrated downtown lunch counters by the end of 1960.

“But it took us four years to actually desegregate all of Nashville,” said Patton.

Patton continued his pursuit of civil rights by becoming a Freedom Rider. As a 21-year-old student, he traveled to Montgomery, Ala., where he met up with like-minded students. They traveled on buses and trains to challenge segregation in the interstate transportation system.

Although the Supreme Court had ruled that blacks could sit anywhere there’s a vacant seat, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) decided to challenge that because it was not the case in the South.

CORE had volunteers signing up from all over in spite of Freedom Riders being arrested, threatened and beaten. When Patton signed up, on May 24, 1961, he signed a will, because “We know that somebody is gonna die” and hopped on a Greyhound bus traveling from Nashville to Jackson, Miss.

When the bus reached Jackson, Miss., he was arrested. Patton was one of 300 African Americans to be taken to the notorious Mississippi State Penitentiary, otherwise known as Parchman Prison Farm, which had a reputation for being brutal.

“We were in a cage waiting to come out to be fingerprinted and booked,” said Patton, who was charged with disorderly conduct and breach of peace. But the Freedom Riders from Nashville, Tenn., were not worried; they knew that every four days a group would be coming from Nashville, Tenn., to Memphis, Tenn., and on down to Jackson, Miss. “That’s how many of us volunteered to go on a freedom ride.”

They turned to music to show solidarity and power. They would sing to let them know more people were coming. They would sing to provide the comfort and protection you only get in homogeneous groups, and they would sing during sit-ins when threatened with violence.

“Music was very, very important to the mood,” Patton said. “If it wasn’t for music, I don’t know what we would have done. When we sing, we announce our existence.”

So, they would sing “We Shall Overcome,” “O Freedom” and “Hallelujah.” Civil rights activist would write freedom songs to inspire hope and show pride.

Patton spoke of growing up and being accustomed to segregation, but through his training, he realized that he could do better. He chose to stop conforming to patterns of the world and instead be transformed by the renewing of his mind.

“I went to those meetings, learned how to remove myself from the situation where I’m being hit, where I’m being thrown over a lunch counter, where things are happening to me,” said Patton.

When asked if he was afraid of taking a stand, he simply replied, “No, I wasn’t afraid because I had signed up, and I was on the bus, and I wasn’t gonna turn back.”

Patton was one of 14 Tennessee State University students expelled for their civil rights activities, although he was later given the opportunity to return. Today, he is a renowned community leader who has told his story on the “Oprah Winfrey Show” and been featured in “Freedom Riders,” a PBS documentary based on the book by the same name.