Jacqueline Hubbard, right, who heads the St. Petersburg Association for the Study of African American Life and History, talks about the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott Decision. Hubbard and Sabrina McCoy, left, organizes Black history lessons for the community.

Caption: Daysha Moore, a freshman at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg campus, attended the teach-in. Moore said she wishes she had learned more about Black history in high school.

BY NANCY GUAN | WUSF

ST. PETERSBURG — Daysha Moore walked into the St. Augustine Episcopal Church on Thursday night with a question in mind: how can students learn more about Black history in Florida?

The Pinellas County native is a freshman at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg campus. When she was in high school, Moore said lessons on Black History were often “compartmentalized.”

“I feel like for so long, in my education, I wasn’t taught about Black history,” she said, “But it’s so important.”

And, for the last several years, she’s witnessed the state first limit how race and history are taught in K-12 schools and then defund Diversity, Equity and Inclusion programs in higher education.

To Moore, those actions were suppressing parts of history that are already “pushed to the side.”

Daysha Moore, a freshman at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg campus, attended the teach-in. Moore said she wishes she learned more about Black history in high school.

“What’s going to happen to the next generation? So many people are going to be left behind through this — and they’re already being left behind.”

At the church, Moore was joined by a group of people who are also seeking more of that knowledge. They gather for a Black History teach-in. Similar events have popped up throughout the community in response to the state’s restrictions on race-related education.

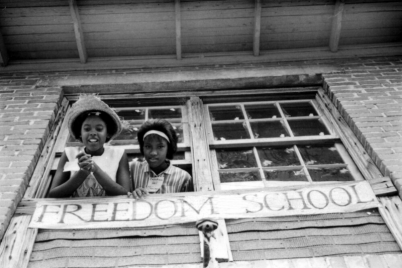

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) in St. Petersburg started hosting classes last year. They’re named after the Freedom Schools that taught African American students during the 1960s.

ASALH President Jacqueline Hubbard said they’re hoping to teach the community a more complete version of history. Their classes so far have touched upon African history and culture through slavery, the Civil War, emancipation, reconstruction, and segregation.

“Black children are not being told the truth,” Hubbard said.

The Stop WOKE Act, enacted in 2022, prohibits K-12 public schools from teaching a list of concepts, including that someone is inherently privileged or oppressed based solely on their race, sex or national origin.

In the last year, the Florida Department of Education changed its African American history standards to comply with state law. The new standards drew national criticism for its framing of slavery and lack of nuance, according to some educators.

The government’s crackdown on race-related issues has caused a chilling effect in classrooms, said Sabrina McCoy, who organizes Freedom School lessons.

“We have teachers who are certified to teach history who are unable to fulfill their mission. It’s really unfortunate because how else are the children going to learn the truth?” asked McCoy.

“But that’s why I’m involved with the Freedom School.”

The program started by reaching out to high school students and has since expanded to the rest of the community at people’s request, said Hubbard. This year’s classes derived lessons from the 1619 Project, a multimedia effort that, according to the project, “places the consequences of slavery and contributions of Black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.”

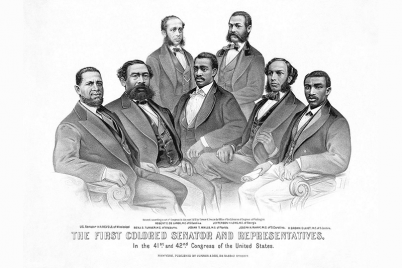

Thursday night’s discussion involved talking about how U.S. institutions have worked against Black Americans since the country’s inception. Part of the lesson involved a viewing of the Hulu-adapted version of the 1619 Project.

Moore pointed to a segment in the video that talked about how Black Americans were largely cut out of the benefits of the New Deal, which created social safety net programs such as unemployment insurance and Social Security.

“The path of history within Black people in America is totally different from white people — and it’s rarely ever talked about,” she said.

McCoy said the community can play a role in filling in the gaps of these discussions. Community teach-ins like the Freedom School don’t operate with the fear of violating state laws.

“I think if we do our part, the information will get out there,” said McCoy. “We have adults here who perhaps have children or grandchildren or are members of another church. If they take the information back, I think there will eventually be this synergistic effect.”

Moore said these teach-ins are also more than just an academic pursuit for her. It’s a personal journey, too.

“Because it’s important to see yourself within education, to see yourself within these structures,” she said. “We’re using community to combat the erasure of Black history … and that gives me hope.”