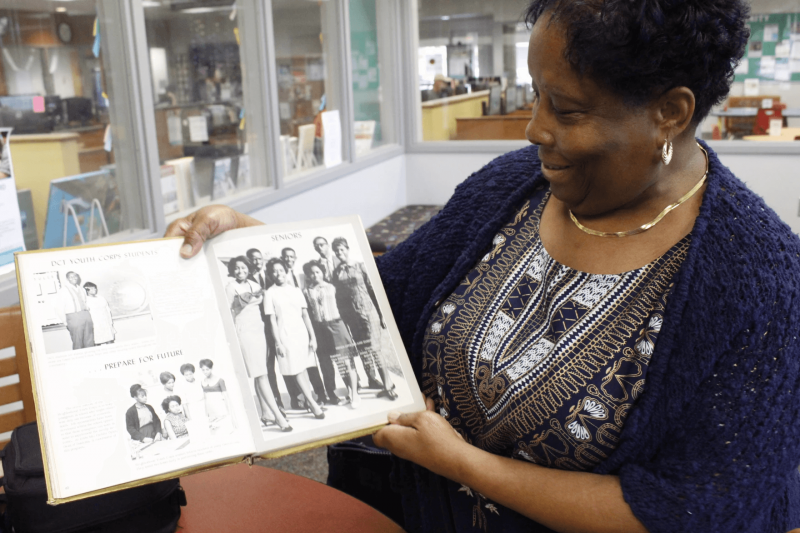

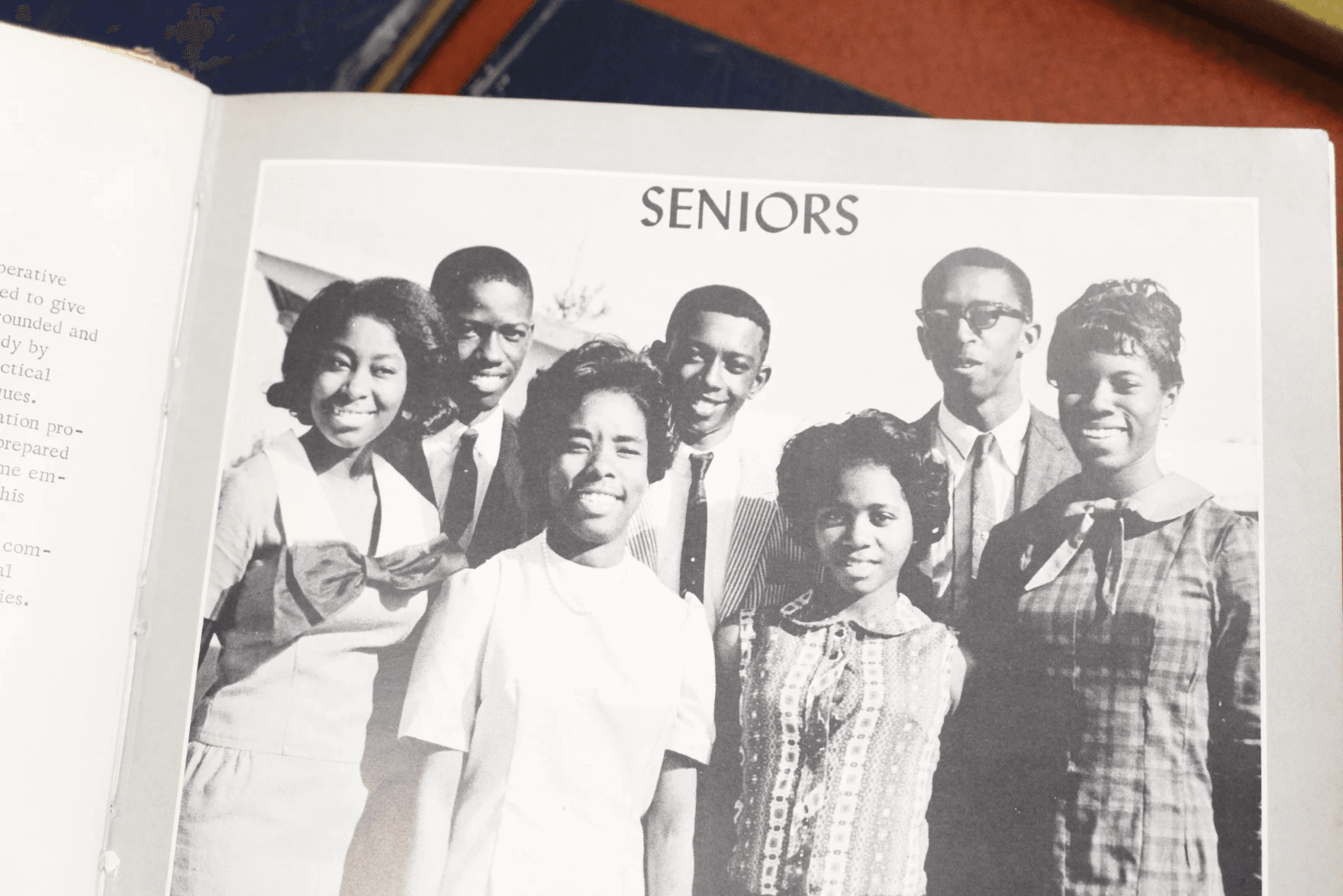

At the James Weldon Johnson Community Library, Lolita Brown flips to a photo of herself in the Gibbs High School’s 1966 yearbook. Gibbs was the first high school for African American students in Pinellas County and was later integrated in 1971. [Nancy Guan]

BY NANCY GUAN | WUSF

ST. PETERSBURG — Leafing through the yellowed pages of a 1966 yearbook, Lolita Brown recalls attending Gibbs High School, the first high school for African American students in Pinellas County.

“All my family had graduated from Gibbs, and I couldn’t imagine not being there,” said Brown.

Brown grew up in South St. Petersburg, in a cluster of segregated neighborhoods, along with the rest of her classmates and teachers.

“Our teachers — we saw them at church, they lived in the community with us. They impacted our lives outside of school. For us it [school] was cultural,” she said.

Gibbs High School, named after the Black public education pioneer Jonathan C. Gibbs, opened its doors in 1927. Prior to then, accessible public education ended at 6th grade for African American students in the area.

The high school became the heart of the community, said 1966 alumna Gwendolyn Reese, who documents history with her group, the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg.

“People always say the church is the mainstay of the Black community, but at that time, it was the school,” said Reese, “because we had many churches, but we only had one high school … it was the educational center, the cultural center.”

The entire community rallied around the events at Gibbs, said Reese. People came out in droves to cheer at football, baseball, and basketball games.

Thomas “Jet” Jackson, who graduated in 1963, played on all of those teams, in addition to swimming. He earned his nickname because of how fast he ran. Jackson said the school was known for its athletics and he loved being part of Gibbs’ winning tradition.

Thomas “Jet” Jackson played multiple sports at Gibbs High School. He says his coaches and teachers made sure he took his studies seriously, too. He’s now retired after working for the city of St. Pete for more than 50 years. [Nancy Guan]

“You could not play an athletic sport at Gibbs with a D average, you had to have a C average in order to play,” he said.

Jackson recalled when one of his coaches refused to let him back on the field until he got his history grade up — and another time when he delayed a game against another Black high school in Miami because he had to finish his homework and clean his room. A bus filled with his teammates waited outside his home.

“I was a laughingstock to Miami,” said Jackson, “but that was fine … I had to do the work in order to do that. And I’m grateful today for that.”

Jackson graduated from Gibbs in 1963. He earned the nickname “Jet” for how fast he ran. [Nancy Guan]

“They lived right next door to us and inspired us, and we aspired to greatness because we saw what it was to dress up in a suit and go to work,” said Reese.

At times, teachers would sit in the cafeteria with students during lunch, giving lessons on etiquette and good manners.

“They’d say, ‘Don’t talk with food in your mouth; take your elbows off the tables.’ You know, kids who couldn’t have learned that at home learned from our teachers,” said Reese.

“It wasn’t just education, they were a part of our lives.”

‘We knew it was wrong’

Outside of school and outside of their neighborhoods, segregation was apparent, and racism was blatant, said Reese.

“We lived on the South Side because of racism and Jim Crow segregation,” she said. “We were very aware of the political atmosphere. I mean, we lived and breathed racism.”

Brown said she remembers hearing about the lunch counter sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina, which set off a wave of similar protests across the South, including in St. Petersburg, where Black youth would occupy whites-only spaces.

“We were very aware of what was going on,” said Brown, “[But] we were never taught to think of ourselves as less.”

More than a decade after Brown v. Board of Education struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine in public schools, Pinellas schools remained largely segregated.

Attempts at integration were at times met with violent threats. It wasn’t until 1971 that the county school board officially started the desegregation process.

Brown remembers the gradual efforts at integration when she was in school. She was one of the first Black students to join the Pinellas County Youth Symphony.

“I wasn’t really that great,” Brown laughed, noting she played the violin. “But we got the opportunity to do it and mix and see other people.”

It was a lived experience for us,” said Reese, “We remember the desegregation of Spa Beach, we remember the desegregation of the Florida Theatre.

“We remember the Black baseball players being here and why Dr. (Robert) Swain built an apartment building for them because they couldn’t stay in the hotels with their white (teammates).

“All of this was a part of life for us. We knew it, we understood it,” Reese said. “Did we accept it? No, because we knew it was wrong.”

‘Got what we wanted but lost what we had’

As integration trickled through the South, neighborhoods gradually began to change. But continued disinvestment, discrimination and white flight kept communities largely segregated.

Urban renewal projects then splintered the Black community in St. Pete.

The Gas Plant neighborhood after homes, businesses, schools and churches were razed but before the gas cylinder was taken down. [St. Petersburg Museum of History]

Other projects, like Tropicana Field, further erased Black neighborhoods, displacing the Gas Plant District.

While some families had the resources to leave, “what was left was those who could not get out,” said Reese.

She mourned the sense of unity that once existed.

Reese, quoting community activist Georgia Ayers, said, “We got what we wanted, but we lost what we had.”

Looking forward

After graduating, Jackson worked with the city for more than 56 years in the Parks and Recreation Department. In 2014, a recreation center was dedicated in his name to honor his service.

Brown attended college in Nashville and worked up and down the East Coast. She eventually returned to St. Pete to work as an educator and college counselor and is now, in her words, “entrenched in the community here.”

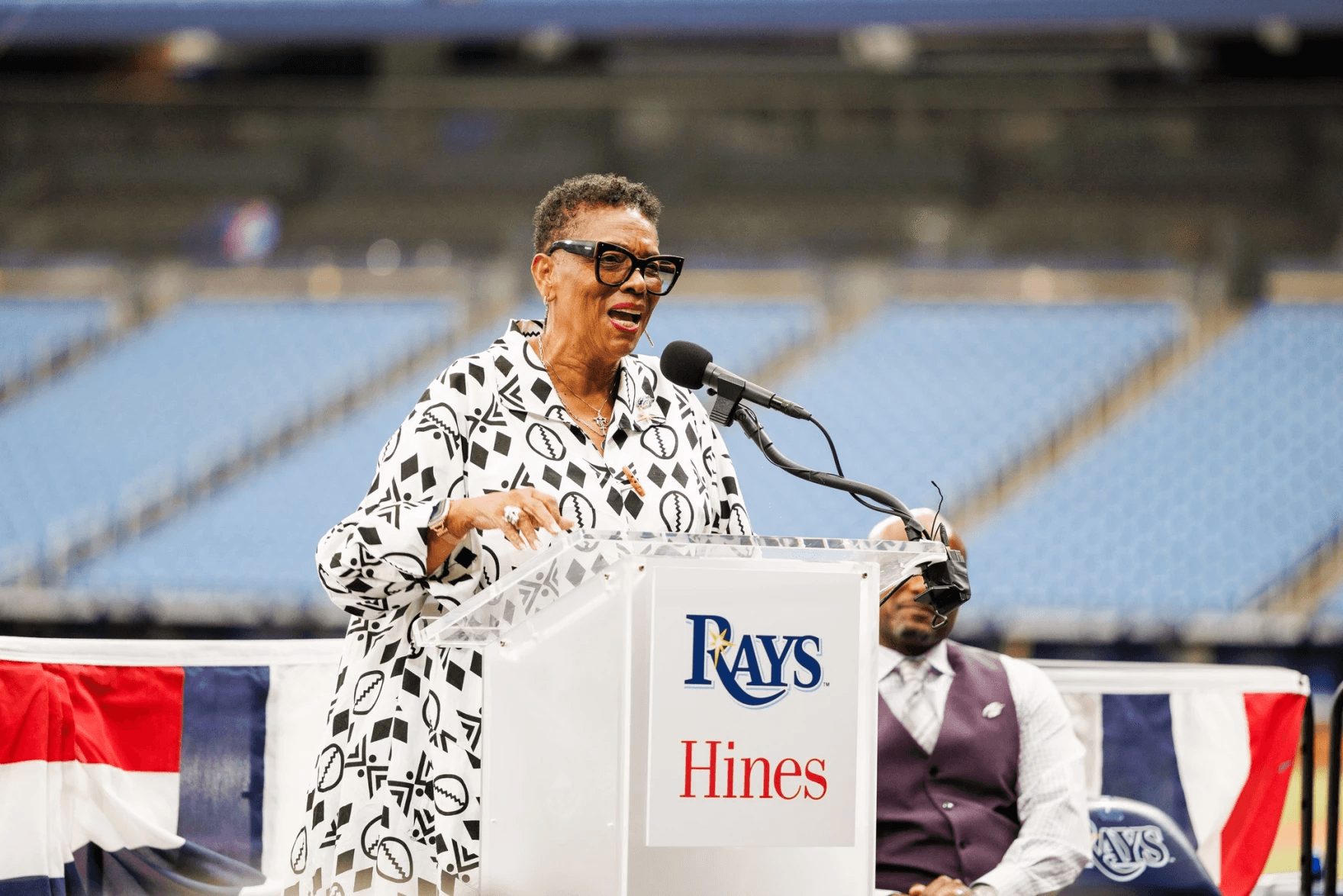

‘I can assure you that our commitment to the Gas Plant residents and to the City of St. Pete is one that I stand strongly in, I believe in, and I know that we will accomplish what we set out to do,’ said Reese. [City of St. Petersburg]

She’s also part of a team tasked with giving input on the largest redevelopment project in Pinellas history — the proposed redevelopment of the Historic Gas Plant District that includes a new Tampa Bay Rays stadium. It’s a project that many residents are skeptical of, but hope will see the city make good on a promise to reinvest in the community.

As much as the Gibbs alumni miss their community, they say they don’t yearn for the past.

Jackson echoes a lesson learned from his time at Gibbs.

“We will strive to move forward, not backward,” he said.

‘We lived it.’ Alumni from St. Petersburg’s first Black high school reflect on desegregation’ was originally published on WUSF.org