BY Jacqueline Hubbard, Esq., ASALH President

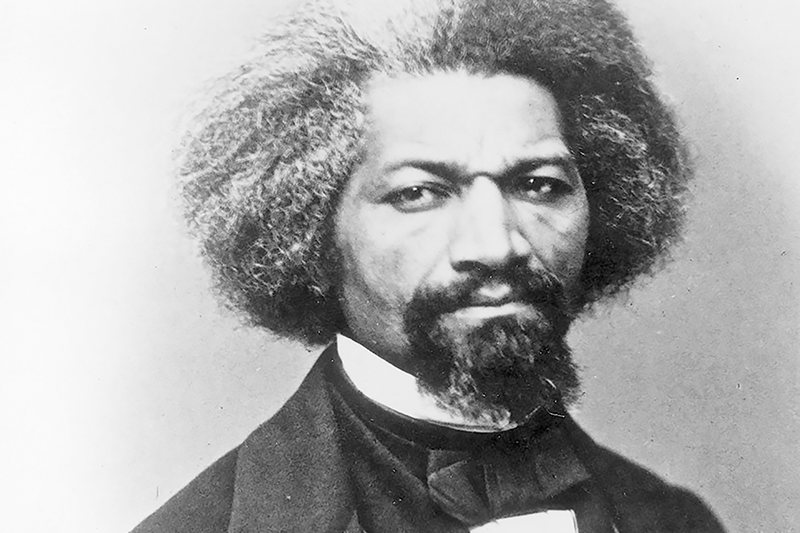

There is one African American who survived slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction and lived to brilliantly write, argue against and tell about it. Frederick Douglass fearlessly championed the anti-slavery cause, women’s rights and other equalitarian issues throughout his lifetime.

Douglass had been taught to read at about age 12 by his slave master’s wife. He was rumored to be the son of his slave master. This did not spare him the psychological and physical abuse suffered by the enslaved.

When he could, he devoted his life to educating himself and others in literature, history, philosophy and political thought and practices. As a teenager, Douglass ran away from his brutal existence in slavery and escaped to Baltimore. While there he met a free black woman named Anna Murray, who assisted him in his final attempt to escape. With her help, he escaped from Maryland using the Underground Railroad at about age 16.

Douglass married Murray on September 15, 1838, and settled in New Bedford, Mass., that same year. Shortly thereafter, he was asked to tell his life story at an abolitionist meeting. He was so successful at speaking that he became a regular anti-slavery crusader.

His oratorical skills made him very effective in the abolitionist movement. The Douglasses had five children together: Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles Redmond and Annie, who died at the age of 10.

After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the federal government assumed responsibility for recovering runaway slaves and demanded the Northern states cooperate. This heinous law denied habeas corpus to captives, rendering even free black people in the North vulnerable to slave catchers.

Douglass lived in constant fear of being captured and returned to his slave master. In 1850, he decided to travel to England to obtain sufficient funds to buy his freedom (England abolished the slave trade in 1834). After two years abroad, he earned enough money from his lectures on the evils of slavery to purchase his freedom when he returned.

One of Douglass’ most famous speeches was given at July 5, 1852, Independence Day Celebration in Rochester, N. Y. He noted the hypocrisy of the occasion stating:

“I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours not mine.”

Douglass further lamented, “Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.”

He had always been considered by his compatriots, the public and historians to be a gifted orator. Upon his return from England, Douglass produced several abolitionist newspapers, including The North Star, Frederick Douglass Weekly, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Douglass’ Monthly and New National Era.

The motto of The North Star was “Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren.” Charles and Rosetta assisted their father in the production of his first newspaper The North Star. Two of his sons fought in the Civil War as Union soldiers in a Massachusetts Colored Regiment and survived the war.

By 1862, Douglass was one of the most famous black men in America. He spent a great deal of time working to influence the powerful and improve the lives of black Americans, especially the black Union soldiers who fought in the Civil War. He tirelessly labored to improve the status of black Americans throughout the United States.

In 1863, Douglass met with President Abraham Lincoln to talk about the treatment of black soldiers in the Union Army. He later met with President Andrew Johnson and attempted to convince him of the importance of black suffrage.

After the Civil War, Douglass served his nation as president of the Freedman’s Savings Bank and as Chargé d’Affaires for the Dominican Republic. Between 1889 and 1891, he was appointed minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti.

Most Americans are unaware of the fact that Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States as Victoria Woodhull’s running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket in 1872.

Over the course of his career, he published three autobiographies “The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” (1845), “My Bondage and My Freedom” (1855) and “The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass” (1881, republished in 1892).

His work spoke directly to the abolition of slavery, the Civil War and its necessity, the need for passage of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution, the Reconstruction Era and the coming dangers of Jim Crow and racial violence after the removal of Union troops and the end of President Ulysses S. Grant’s second term.

Needless to say, after the war ended in 1865, Reconstruction became a time of both hope and great peril for African Americans. By 1877, the North had grown weary of the ramifications of the Civil War and Reconstruction and desired reconciliation with the southern states and reunification, even at the price of racial violence against the newly freed.

Reconstruction ended shortly thereafter and with its end came a resurgence of violence against black Americans, the re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan and racial segregation that continued for another 80 years.