Community activist Jabaar Edmond said overcoming the feeling of powerlessness that he once battled has been life-transforming and has become a motivating force.

BY J.A. JONES, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Jabaar Edmond is a modern-day renaissance man whose activism takes various forms: he’s a filmmaker, neighborhood leader, entrepreneur, magazine publisher, and tireless community advocate. It is always comforting to see him in any room because there’s a good chance vital issues of change are being discussed and the status quo being questioned and probably documented — by him.

Community members know him from his work on numerous issues, from Amendment 4 to handing out COVID supplies and meal giveaways with Community Development and Training (CDAT), the organization he helps lead along with Brother John Muhammad.

More recently, they’ve seen him participate in the fight to bring affordable housing to St. Pete and as a member of the team that put together the historic structural racism study conducted by the University of South Florida last year.

Born and raised in St. Pete, Edmond recalled how he got involved in community work a decade ago after receiving the call from fellow photographer, the late Rassi Dennard.

“I’ve been active in my community 10 years this year, volunteering actively at Childs Park Neighborhood Association. I’m vice president now,” he said.

The tragic murder of 24-year-old mother Tamika Mack brought him to activism, and the life-changing sense of possibility to impact his community further made him stay.

“I started volunteering at the vigil they had for her after she had passed; I was asked to come take some pictures and film. There I met Brother John (co-founder of CDAT), and I met Momma Tee (Theresa Lassiter). I really met a lot of the community members and community activists that day and exchanged a lot of phone numbers and just started getting more and more involved as time progressed.”

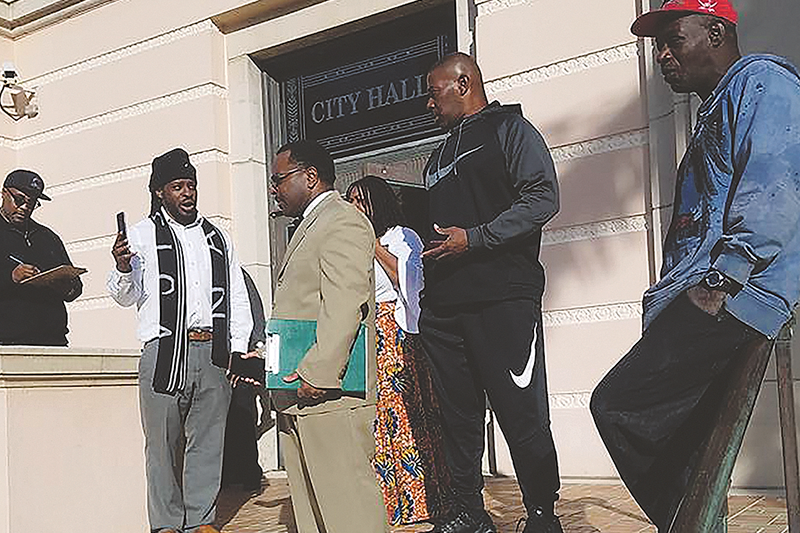

Jabaar Edmond (left), Brother John Muhammad and others gathered at City Hall to protest the treatment of Black citizens on Martin Luther King Day in 2018.

Edmond marvels at the changes he’s experienced from being involved in community change, and he feels that collaboration is one of the most critical strategies he’s learned to use. “Actually, collaboration in action,” he stresses, noting that it’s collaboration to make positive change that makes a difference.

Another empowering lesson for Edmond was learning that his voice mattered. “Sometimes, growing up in impoverished communities, you don’t feel what you have to say or what you have to offer matters. What I learned is that what I have to say and what I have to offer matters. And not just me, but all of us.”

He shared how overcoming the feeling of powerlessness that he once battled has been life-transforming and has become a motivating force. “Just coming from a place of helplessness to being able to help, being able to contribute — that’s something that I learned that really sticks with me to this day.”

Acknowledging the work of community healers like Dr. LaDonna Butler as necessary, he has also learned how childhood and family trauma, on top of systemic racism, has played a role in destabilizing the environment.

“Childhood traumas, especially in my community, a lot of times go unaddressed, a lot of times we don’t confront it, or we don’t necessarily always have the tools to deal with [it]. I think what LaDonna and The Well are doing should be commended.”

He added that realizing many people are still dealing with trauma that has gone unaddressed for decades makes the work Butler and others do very crucial.

He noted how toxic mindsets like hopelessness could lead to even greater disparities and tragic outcomes. “Hopelessness, like I said, I dealt with myself. Not feeling that [you’re part of] the world of the community — that you’re not enough.”

‘For me, volunteering and being involved with the community is one of the things that helped me see that hey, ‘your voice and what you’re doing,’ you should have some hope for the future.’

Edmond credits those around him doing positive work with helping him find his way out of that negative mindset.

“For me, volunteering and being involved with the community is one of the things that helped me see that hey, ‘your voice and what you’re doing,’ you should have some hope for the future.’”

He noted that systematic racism often leaves those in the community feeling hopeless and is especially detrimental when youth in the community feel despondent.

“Then, with that hopelessness, sometimes they’ll do a whole bunch of things that they will regret in the future. Youth and adults — we have to have some type of hope in the future, hope in what we’re doing. Because being hopeless is toxic. And it’s so toxic, it affects your brain, it affects your thought process.”

Edmond also noted that toxicity is often contagious and travels throughout families, neighborhoods, and communities.

“Just going through different stuff in the community and hearing people say, ‘Oh, that ain’t gonna do nothing for you,’ — no matter what the situation will be. It’ll always be like an undercurrent of ‘Oh, well, that’s just how it is,’ or ‘ain’t nothing you can do about it…they ain’t gonna listen to you, they ain’t gonna listen to me.’”

But Edmond insists we must push back against the “mysterious ‘they’ who has this oppressive force over our community…that creates the hopelessness, and then it gets passed around through word of mouth.”

He noted that often it may not be an experience the person passing on the toxicity may have personally had, but rather, “just what someone told me about an experience…or what somebody says and I subscribe to it, and then, it grows.”

Well respected and looked to as a community change agent, Edmond has a long working history with other brothers on a similar mission to change outcomes in St. Pete.

That includes Antonio Brown, also a member of CDAT, owner of Central Station Barbershop & Grooming, and founder of the Barbershop Book Club. Brown likened Edmond to the character of Freeman in Sam Greenlee’s 1969 novel and 1973 film “The Spook Who Sat by the Door,” about an activist trained and knowledgeable in the ways of the oppressive forces working against his community, who is still committed to changing the environment with the resources he can muster.

“Jabaar is well educated as far as his community background; he’s very experienced at what he does. He’s dedicated; there’s nobody that I know that is more committed than Jabaar when it comes to this type of community engagement, advocacy work, and the representation he’s been doing for the community for the last decade,” shared Brown. “I think Jabaar is a key piece on the chessboard in our community because he’s so involved and dedicated to seeing change and being a part of the change — and actually being an example of that.”