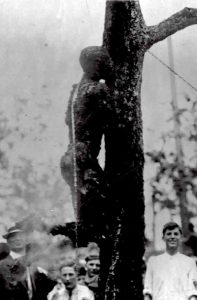

Teenager Jesse Washington was lynched and burned in Waco, Texas, on May 15, 1916.

By Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard, President, ASALH

Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Prize winner, author, political activist, and Holocaust survivor, often spoke of the need to remember the Holocaust, which resulted in the killing of 6 million Jewish people in Europe during World War II. Of himself, he wrote, “For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear: his duty is to bear witness for the dead and the living. He has no right to deprive future generations a past the belongs to our collective memory. To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive to forget the idea would be akin to killing them a second time.”

This quote also applies to African Americans. We cannot forget, in fact, it behooves us to learn more about the history of lynching in America, which was an inhumane, horrific and systematic method of terrorizing African Americans from the period of Reconstruction after the Civil War to the 1950s, and undoubtedly later.

It was used to put black people–in what many white Americans believed to be–in their place and deny them their rights as American citizens, especially the right to vote under the United States Constitution.

The Civil War was fought to preserve the institution of slavery. Eleven states, all from the South, seceded from the Union and in 1861 the war began. The people in power in these southern states firmly believed in the subordination of black people and that political power must forever be in the hands of white people.

Many whites believed the institution of slavery would last forever. As the war dragged on, many former slaves escaped to the North and the Union Army; and after two years of war, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, which stated that slaves held in the Confederate states would be “thenceforward, and forever free.”

There was much resistance by the southern states and the slave owners; however, the actual abolition of slavery nationwide did not occur until 1865 with the ratification of the 13th Amendment. By that time, racial inequality had been ingrained in American society since the first arrival of black people off a Dutch slave ship in 1619.

Emancipation, this official freedom from slavery, prompted a great upheaval in southern society. There was great resistance to relinquishing racial power. White supremacy was a deep part of the American belief system before and after the Civil War, and even to this day.

Immediately after the Civil War, (since the rebellious Confederacy and those who fought to preserve its way of life were forbidden to vote), black Reconstruction began, and for the first time in American history, black men were given the right to vote. As a consequence of doing so, and getting elected to high state offices and to the United States Congress for the first time, a vicious backlash began.

Black people began to be killed just for exercising their right to vote. The only thing that kept more black deaths from taking place was the use of Union soldiers, who were placed throughout the South by President Ulysses S. Grant.

The beginning of helpful institutions such as black public schools, colleges and universities, medical and dental schools, the Freedmen’s Bureau, the introduction of a banking system that could be used by black Americans, and the prosecution and dismantling of the Ku Klux Klan by the federal government were extremely helpful.

When the Union Army protection ended around the late 1870s, lynching began en masse. In the report entitled “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror” by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), “Mass incarceration, excessive penal punishment, disproportionate sentencing of racial minorities, and police abuse of people of color reveal problems in American society that were framed in the terror era. The narrative of racial difference that lynching dramatized continues to haunt us.”

EJI has verified 4,084 lynchings of black people occurred between 1877 and 1950. Two documented lynchings happened here in Pinellas County. This was also the period of almost absolute racial segregation, Black Codes (separate laws pertaining solely to black Americans throughout the South), and Jim Crow.

According to EJI, “By 1890, the term ‘Jim Crow’ was used to describe the subordination and separation of black people in the South, much of it codified and much of it still enforced by custom, habit, and violence.”

The lynchings were atrocious. Black men and sometimes women were hung from trees with ropes around their necks, from scaffolds, and from railroad tracks. Some were beaten, maimed, cut, and burned alive while hanging.

Many were public spectacles, advertised in local newspapers as to the time and location of the lynchings. Most were without any real evidence of any actual crime having been committed. Black men were often convicted of rape, solely on the word of a white female, arrested, taken from jail and lynched.

Blacks in the South were terrorized if they violated any social law defined by white people, intentionally or accidentally. This reign of terror was legitimized by those whites in positions of power.

According to EJI, black subjugation was achieved by any means necessary, and white perpetrators faced no legal repercussions. Between 1877 to 1950, Florida has been documented to have perpetrated 311 lynchings, Louisiana 549, Mississippi 654, Georgia 589, Arkansas 492, and Texas 335.

In looking for relief, African Americans turned to the black press. Anti-lynching forces gathered around the black press such as the NAACP and freedom fighters such as Ida B. Wells, T. Thomas Fortune, and Monroe Work, a sociologist at Tuskegee Institute.

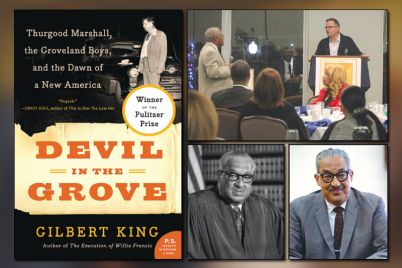

By the 1950s, the Civil Rights Movement was well underway, and lynchings began to subside. Black Americans took the struggle to the ballot box and to the courts. Thurgood Marshall, Charles Hamilton Huston, Charles White, and others became “lions of the law” in the civil rights fight. This new phase of the struggle for human rights for black Americans opened a brand new era in American history that is still ongoing.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.