Norman E. Jones, Sr.

By J.A. Jones, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG –Norman E. Jones Sr. was an iconic figure in Tampa Bay for more than four decades, known for his conservative viewpoints that often ran counter to the times.

Kansas born, Jones studied photography in high school then spent time in Memphis while attending Henderson Business College. By the time he landed in Tampa in 1950, he was prepared to find his niche in journalism and was soon publishing The Tampa Star (1952 – 1955).

He edited the black pages of the St. Petersburg Times and St. Petersburg Evening Independent, while his column “Let’s Talk Politics” ran in various black newspapers throughout Florida for almost 20 years. His radio program ran on two Tampa stations, while his self-titled television program could be seen on WTOG-Channel 44 for close to two decades.

Jones was strong on a message of self-reliance and was against integration at a time when the most outspoken black voices were fighting against segregation.

Still, the impact Jones made a black voice in media would catapult him into the history books. And as the head of his own St. Pete-based advertising and public relations firm, until illness led to his retirement in the ‘70s, his wide-reaching footprint guaranteed his status as a pioneer in the communications world.

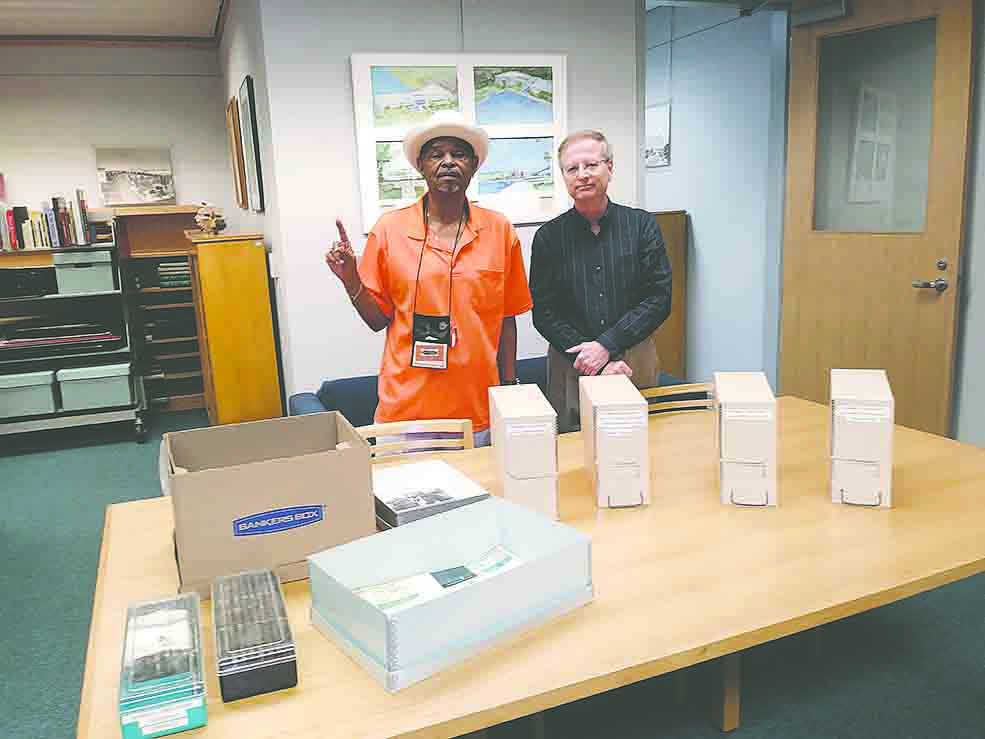

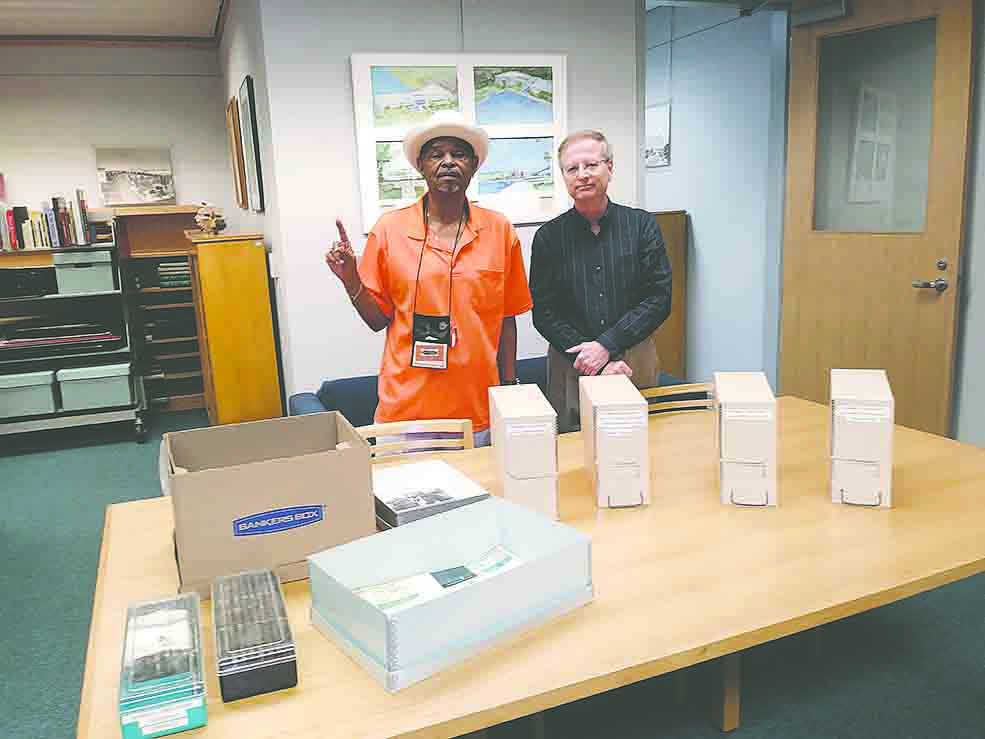

Norman Jones II, left, and David Shedden

In 2001, a collection of Jones’ writings, recordings and photos were donated to the Nelson Poynter Memorial Library Special Collections at the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg by his son Norman Jones II and his widow, Mary Brayboy Jones.

The archive includes copies of typed drafts of Jones’ book “Let’s Talk Politics,” publications from the Norman E. Jones Agency, unpublished manuscripts, as well as vinyl recordings of his radio show and over 60 hours of audiotaped cassette interviews.

Recently, Norman Jones II visited his father’s archives at the USFSP and discussed the importance of the archival collection that includes official documents, letters, proclamations, government activities, photographs that he took and photographs of him that were taken for newspaper articles.

“There are more than 8,000 pieces of activities that he’d done in his life, along with 40 audiotapes of his life and the life of blacks in America,” said Jones II. “He also has correspondence from Langston Hughes, playwrights and other interesting, one-of-a-kind things that you couldn’t find anywhere else but here.”

This collection is a treasure trove for those researching African-American history.

Archivist David Shedden has been assisting with the organizing of the materials in the library’s repository. He commented on the variety of visitors that come through the archives to view the materials, which include not only students and faculty, but researchers, filmmakers and historians.

“We are a university so our primary focus, of course, are students. But over the years, and these materials have been here approximately since 2001, there have been many people who have been able to use it,” Shedden remarked. “But that’s one of the great things about history that 30, 40, 50 years from now people will continue to use these materials. So, we’re really grateful that they found a home here.”

Jones II, a journalist, author and community activist, has his own collection alongside his father’s. In his memoir “The Art of Livin,’” he chronicles his journey of finding his father.

“My father separated from my mother in 1948 when I was four years old and he traveled throughout the country before and after his marriage to my mother. At high school age around 13, 14 or 15, I began an effort to look for my father to shake his hand for his participation in my life,” he said, revealing that he found him right here in St. Petersburg in 1972 after a 10-year search.

Already a young journalist at the time, Jones II acknowledged that upon locating his father, the realization of their similar career paths wasn’t lost on him.

“Upon finding him, I found the Norman E. Jones that is an icon in this community. So when he passed in 1990, I inherited his memoirs and I organized those memoirs for presentation to the University of South Florida so that they could be preserved. And now they have been preserved, and now we are talking about them today.”

Visitors can also examine the numerous historical African-American periodicals, journals and catalogs Jones II has amassed in the collection that resides along with his father’s.

“What I did was donate my travels throughout America for the last 50 years, collecting black paraphernalia, magazines, travel guides, black history associated material. So, he has his collection and I have my collection.”

Norman E. Jones Sr.’s archive at USFSP is also part of “The Civil Rights History Project: Survey of Collections and Repositories” supported by Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center collection. For more information on the Norman Jones Papers, visit The American Folklife Center.

Post Views:

6,985