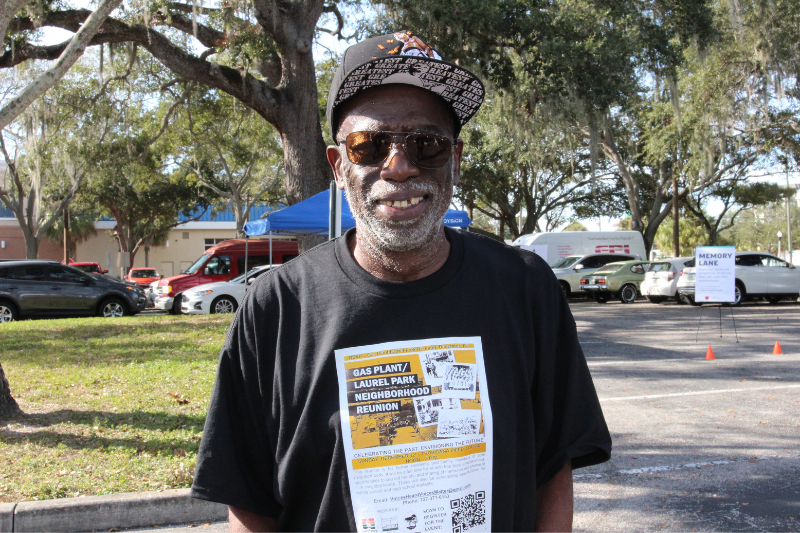

“We looked after our neighborhoods just like everybody else,” Joe Sherot said.

By Frank Drouzas

ST. PETERSBURG — Hundreds of Black families, businesses, churches, and community spaces were displaced or destroyed by the construction of Tropicana Field. Former residents of the Gas Plant and Laurel Park neighborhoods and their descendants share memories of a safe, supportive, and thriving community and the lasting impact of its demolition.

The story of the Gas Plant and Laurel Park neighborhoods is unique to Pinellas County and has a history repeated across this country and generations of Black and Brown communities. If we are to move forward with race equity, we must know, understand, honor, and be changed by our collective past.

Joe Sherot is genuinely a product of the Gas Plant area, as he was born on Dixie Avenue and raised on Dunmore Avenue. During his middle school years, he moved with his mother to Laurel Park until he departed for the service in 1966 at age 19. He remembers it being a close-knit community.

“We looked out for each other back there,” he recalled. “Everybody was close.”

Though he recalls the police unfairly labeling him and his friends back then as “thugs” and “gangsters,” Sherot attested they all cared about their neighborhood. They were labeled the “Third Avenue Maniacs,” but they were determined to do good, such as raising donations for local businesses.

“We looked after our neighborhoods just like everybody else,” he said.

As this was during the Vietnam War, Sherot saw many of his friends get drafted. Others went in different directions — some to places of higher learning, some to the workforce, some even to prison.

“Everything in our hood was kind of breaking up,” he said.

He recalled the joyful times before then, like meeting friends in neighborhood establishments, playing music on the jukeboxes, and enjoying one another’s company.

“We did a lot of things together,” Sherot said. “Back then, there was a closeness.”

He spoke about a childhood where he and his friends would gather different parts of a bicycle until they could put them all together to make one bike or even fashion a scooter by nailing a board to roller skates. These experiences helped bring them together, and he believes young people are missing out on that fun these days.

The neighborhood parents set a curfew to help corral all the youngsters back then, Sherot said, and they all respected it.

“When them lights come on, them streetlights come on, you better be in front of the house! Now, you don’t have to be in the house, but you’ve got to be in front of the house,” he laughed.

A man named Pete, one of Sherot’s closest childhood friends, was born on 10th Street in 1949. He recalled how Sherot and his friends would look after him and made sure he would stay out of trouble, even though sometimes it was tough to avoid.

“We did what we had to do,” Sherot said. “We worked, we hustled, we did what we had to do back then.”

In a time of the Civil Rights Movement and the war in Vietnam with the ensuing draft, Sherot said young people back then had to grow up fast. Fast forward to today, and he believes he is still fighting some of the same battles, like racial bias and voter suppression.

“I’ve been going through this for 74 [years], and in a way, I’m still going through it,” he averred. “Why you hate someone because of the color of their skin? That’s so stupid.”

He lamented that after the building of what became Tropicana Field in the 1980s, no shops or businesses sprung up around it as promised. Yet still, Sherot said he always aims to do what he can to improve his community.

“This is my community,” he said, waving his arm around to indicate the Gas Plant/Laurel Park reunion. “I love it; I’m trying to do my part to make it better.”

Click here to watch videos of residents recalling their gas plant memories.

Joe Sherot recorded his memories of growing up in the Gas Plant District on Dec. 12, 2021, at the Gas Plant/Laurel Park Reunion.

Joe Sherot recorded his memories of growing up in the Gas Plant District on Dec. 12, 2021, at the Gas Plant/Laurel Park Reunion.