By J.A. Jones, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – The James Museum explores work by a brilliant firebrand in the rich tradition of Native American art in the exhibit “Spirit Lines: Helen Hardin Etchings,” on view through March 1.

The first featured exhibit by a female artist, the etchings offer a profoundly spiritual and visually exciting addition to the James’ mission of displaying the beauty of the American West.

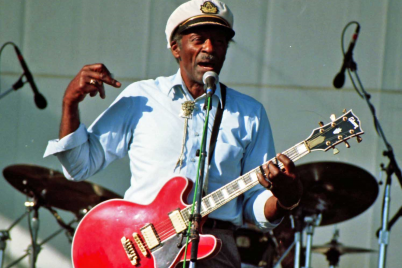

One of the most recognized Native American artists of the 20th century, Hardin rose to a kind of rock-n-roll stardom in the early 70s, in a field largely dominated by white males. America’s “countercultural” movement and ever-fickle art world embraced Hardin after she posed on the 1970 cover of New Mexico Magazine and was heralded as bringing a “new look” to Native American art.

It wasn’t all hype: the James’ exhibit offers a dynamic sample of Hardin’s unique and striking approach to depicting Native American themes through intricate, linear designs that evoke the sense of “ordered, patterned” myth, magic, and mysticism inherent in the natural world.

Born May 28, 1943, in Albuquerque, N.W., Hardin was raised among the Tewa tribe in New Mexico’s Santa Clara Pueblo during her earliest years – her paintings are signed in her Tewa name, Tsa-sah-wee-eh, (“Little Standing Spruce”) honoring her first language.

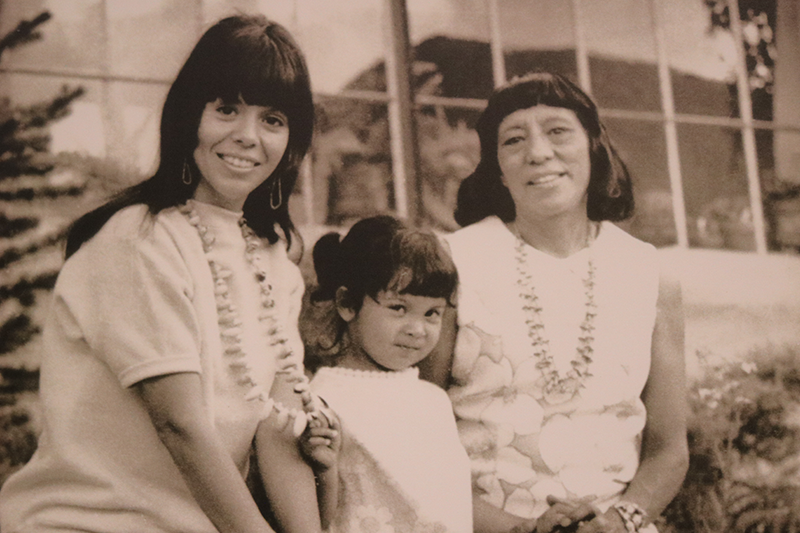

The daughter of renowned Pueblo artist Pablita Velarde, Hardin’s father Herbert, was an “Anglo” police and public safety officer — and Hardin walked a tightrope between the two cultures throughout much of her life.

Raised on the pueblo until the age of four, Hardin’s family relocated to Albuquerque, where she was brought up Roman Catholic. Ensconced in a more traditionally “Anglo” coming-of-age experience, she was schooled in a mostly white environment. As Hardin put it, she was “Anglo socially and Indian in [her] art.”

Already winning prizes for her art by the age of six, Hardin often accompanied her mother to art shows and cultural events and started selling her work by the age of nine.

While attending a Catholic high school, Hardin learned to use drafting templates, rulers, and protractors, tools that would later prove invaluable to her creative inspiration. Teenage years in Arizona’s Southwest Indian Art Project and architecture and art classes at the University of New Mexico also exposed her to new techniques and influences.

As her interest in art deepened, her relationship with her mother became difficult. Velarde, a traditionalist whose “flat style” of painting was the Native norm at the time, was not a fan of Hardin’s more experimental art – and she wanted her to go to business school rather than follow painting as a career path.

When her parents divorced, Hardin’s father moved to Bogota, Columbia. A relationship with a high school sweetheart resulted in the birth of Hardin’s daughter, Margarete, but when the father became abusive, Hardin fled with her daughter to live with her father in Bogota.

It was during her time in Bogota she found her true style and unique voice; a successful exhibit at the American Embassy resulted in Hardin’s selling 27 paintings.

By the time she returned to the U.S. in the late 60s, she was ready to branch out even further with her unique vision — combining familiar Native themes and objects — corn, women, chiefs, and katsinas (or Kachinas, heavenly messengers) – with her intricate geometric designs.

The meticulous nature of her work, soon to become in extremely high demand, meant she worked slowly, resulting in minimal output. In 1980, she began creating limited edition prints of her work through a complex copper etching process. Diagnosed with breast cancer a year later, Hardin died in 1984 but left behind a body of work revealing her visions, spiritual roots, and internal questions.

In discussing her Women Series, on view now as part of Spirit Lines, Hardin called one of the three paintings, Changing Woman, a “self-portrait”: “I call it Changing Woman…about every six years I become aware of myself as a woman, as a person growing through changes. I shift gears,” Hardin explained.

Along with Hardin’s work the exhibit includes paintings by Hardin’s mother, Pablita Velarde, sculptor Tammy Garcia, potter Sara Fina Tafoya, and Hardin’s daughter, artist Margarete Bagshaw.

The James Museum is located at 150 Central Ave., St. Petersburg. Open daily 10-5p m., and Tuesdays from 10-8 p.m.

For more information, please call 727. 892-4200 or visit thejamesmuseum.org.

To reach J.A. Jones, email jjones@theweeklychallenger.com