Corey Givens, Jr., a fourth-generation native of St. Pete, is a descendant of family members that were interred in the original Oaklawn Cemetery, one of the city’s “lost” cemeteries.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is an ongoing USF research study that addresses the erasure of historic Black cemeteries in the Tampa Bay area. Awarded a USF Blackness and Anti-Black Racism grant in 2020, it consists of faculty, staff, and students from multiple disciplines across USF St. Pete and Tampa campuses.

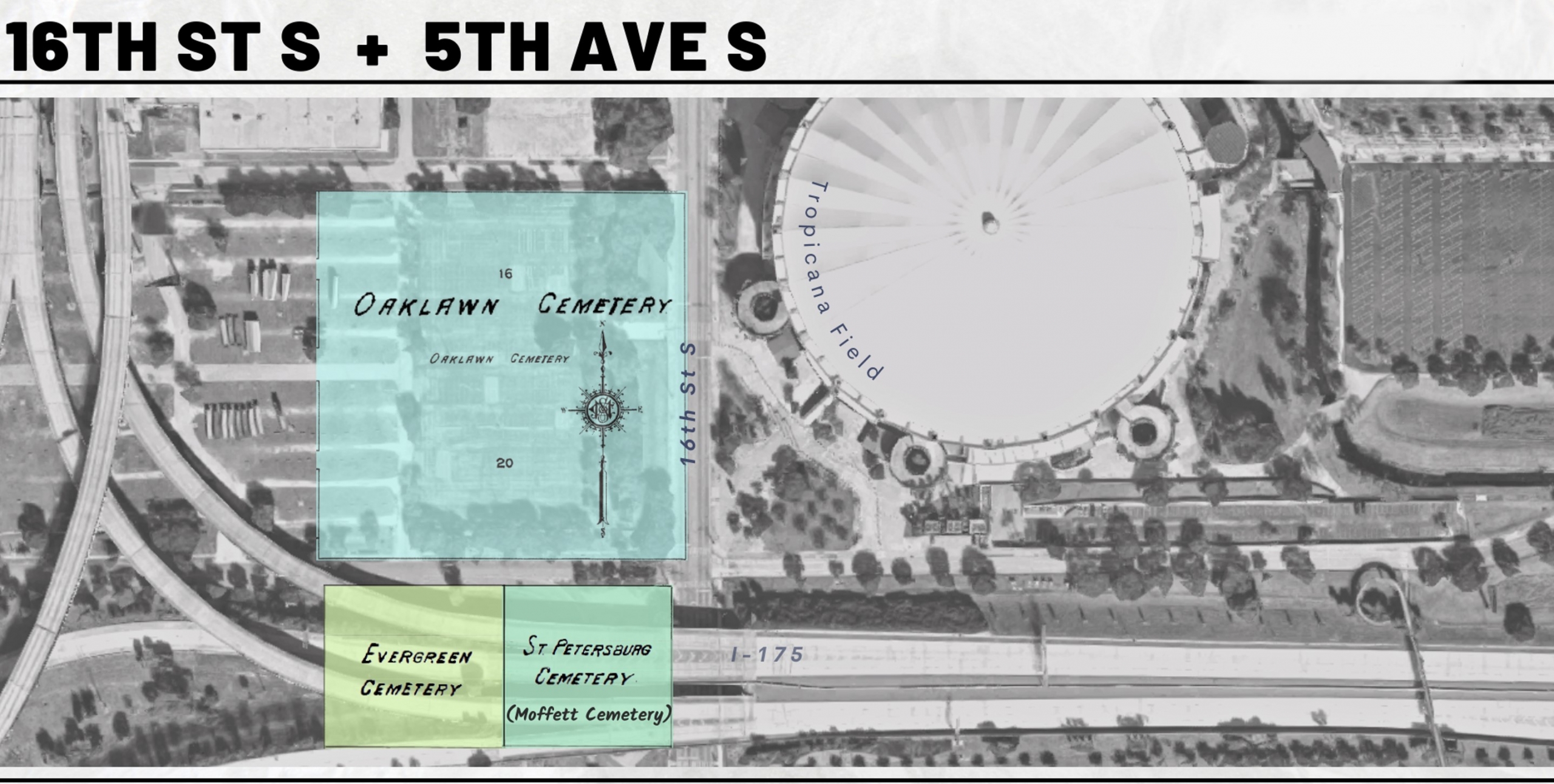

The project focuses on activities to identify, interpret, preserve, record, and memorialize previously unmarked, erased, abandoned, and underfunded African-American burial grounds in Florida, with a focus on Tampa’s Zion Cemetery (located beneath Robles Park Village) and St. Petersburg’s Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries (located beneath a Tropicana Field parking lot and I-275).

Image provided by the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg campus library.

One aspect of the African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is recording oral histories of those who remember or are related to those lost to time.

Corey Givens, Jr., a fourth-generation native of St. Pete, is a descendant of family members interred in the original Oaklawn Cemetery, one of the city’s “lost” cemeteries. His family lived and owned businesses in the Gas Plant district, so he is one of a long line from the city’s early settlers.

His family also worshipped in the Gas Plant area.

“New Hope Missionary Baptist Church, which was off of Seventh and 15th Street,” Givens explained. “And we owned a business there as well. My great-grandmother had a tailor shop there, and we also had cousins, the Welches, who owned a lumber shop as well as … dry cleaners over there.”

To his knowledge, his great-great-great grandfather Anthony Givens, who helped construct the Orange Belt Railway, was buried at Oaklawn. Also laid to rest were a great-great aunt, Dorothy Beachum, and a great-great-great uncle, Will Dukes, who was also the founder of Friendship Missionary Baptist Church.

Evergreen and Moffett were other African-American cemeteries that are considered lost or erased.

“I know the latter of the two, Evergreen and Moffett; they were sort of birthed after Oaklawn,” Givens said. “Oaklawn was the original cemetery of some of the early pioneers and settlers of what they considered south Pinellas. You know, at that time, St. Petersburg hadn’t really been annexed from Hillsborough County yet, so we weren’t our own official city until the — until I believe, 1902. But some of the early, early settlers of St. Petersburg were buried in Oaklawn.

Givens’ church, New Hope, was relocated because of the interstate coming in in the 1970s. It was relocated to 2120 19th St. S.

“Now, a lot of people assume, well, since this is a Black church, that must be a Black cemetery,” Givens said. “Well, that wasn’t the case. Those cemeteries were specifically created for white parishioners who attended those white congregations, those white churches.”

Since St. Pete was such a staunchly segregated town, Black people buried their loved ones where they lived in segregated enclaves, which means those who lived in the Gas Plant district buried them in either Oaklawn, Evergreen, or Moffett.

“…once the city condemned these cemeteries, I think in the late ’20s or ’30s, then that’s when they began relocating the bodies and reinterring them at Lincoln Cemetery, which is in Gulfport.”

Because there was such poor record keeping at the time, Givens said, only a few people were notified of where their loved ones had been moved.

Givens recalls hearing stories of his uncle, who was a child in the 1950s. As a kid, his uncle would play where the current parking lot is and fall, trip, or dig up items that were not properly exhumed.

“And so, a lot of rubbish was left behind for people to discover,” he said. “Kids who were just playing around would sometimes stumble across jewelry or old clothes that had been discarded or just left behind from a decaying corpse.”

The city had condemned Oaklawn in the 1920s though there were still some headstones that remained there. By the 1950s, urbanization started taking place and constructing more housing units for low-income Black families.

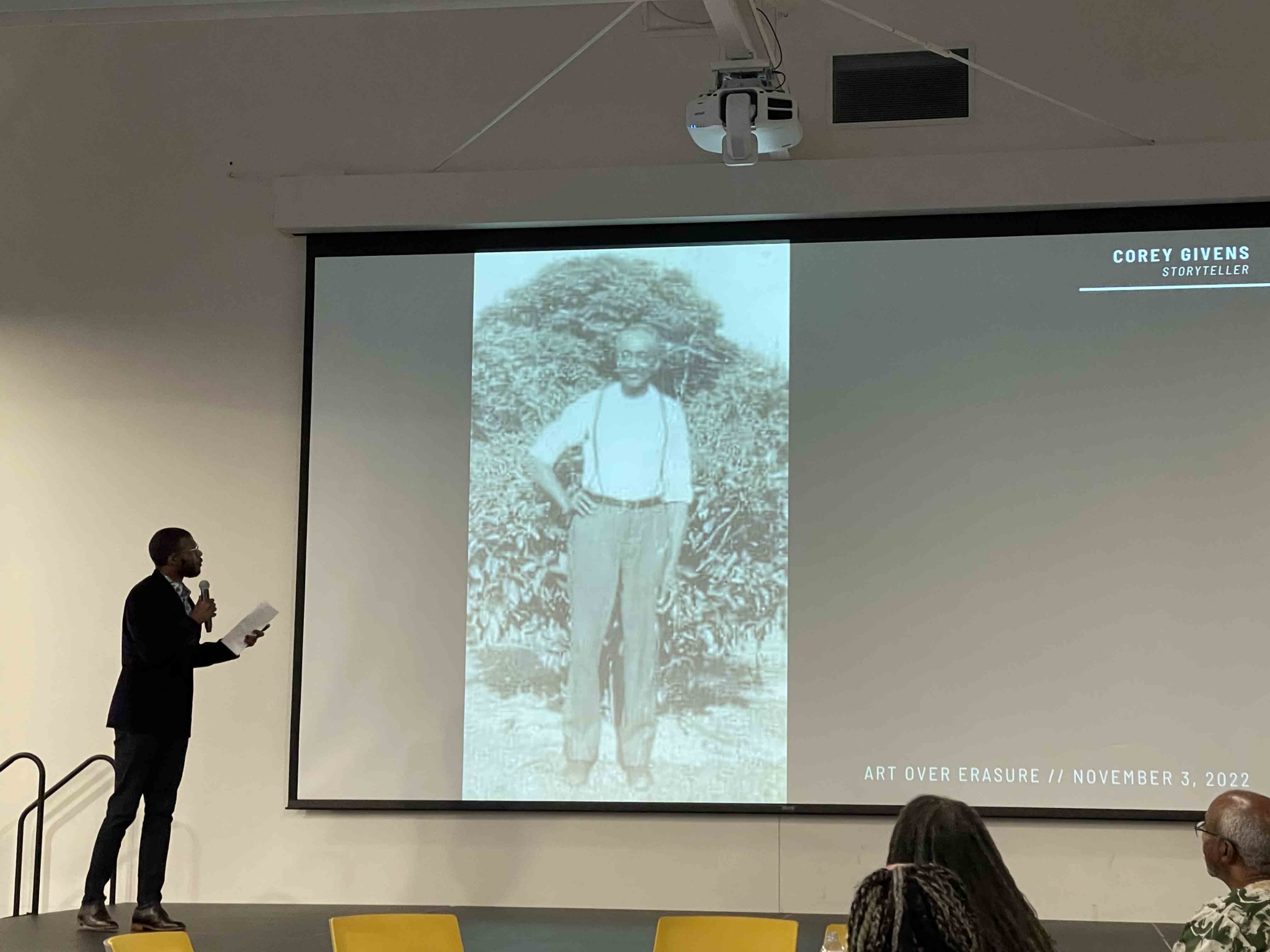

Corey Givens, Jr. gave a presentation on his descendants lost to history in St. Pete’s erased cemeteries at the ‘Art Over Erasure’ event last November.

Givens’ family was never given word as to what became of their descendants’ remains, whether it was from McRae Funeral Home who reinterred the bodies in Lincoln Cemetery or anyone else.

“No one ever notified us to tell us where these bodies had been relocated, from this plot to that plot,” he asserted. “So, it was almost like we were blindsided.”

To this day, Givens said, no one knows where the remains of his uncles, grandfather, or aunt are. Because the funeral homes kept no accurate record, he pointed out, and no record kept through the city or the county, “it was almost like a mass discarding of unwanted graves.”

“Nine times out of 10, because the bodies have been here for a couple of decades, loved ones no longer are around, or they no longer care. And I think it was just simple — simply a matter of race … these were African Americans, and therefore, the city had no respect for those deceased. That’s what I think it came down to.”

Givens said he was jaded and disgruntled when he read about the mistreatment of Black bodies.

“You know, the same team that I loved seeing play here at the home games was the same team that basically destroyed the final resting place for our Black community. And I don’t want to fault the team because I don’t think it’s the Rays’ fault. I also don’t want to fault urban development because I don’t think it was necessarily Royal Court’s fault … the blame has to go on those who were in leadership at that time.”

He pointed out that whether it was the county or the city, someone could have taken the onus of doing their due diligence and surveying the land.

“I know at that point, there were no instruments to go out and to do that, but they could have done as much homework as possible to notify the families of those who were buried there, so that way we could have had some peace, some solace in knowing that, okay, our loved ones now rest here, versus wondering where they’re resting at, whether it’s under a parking lot or at Lincoln Cemetery,” Givens said.

He believes much confusion could have been avoided had there just been some communication. Communication was lacking, and as a result, many families like Givens’ were blindsided and left in the dark.

As to what to do for the people who were once interred in these resting places, Givens believes they should be honored.

“I think we should pay honor to them — definitely give honor to the memory of those folks, as well as the memory of the legacy that was built there in the Gas Plant district,” he said.

Givens is pleased to see that some people in the Florida legislature are fighting to make sure that there are dollars dedicated to preserving the history and honoring those lost cemeteries, such as Zion over in Tampa.

In addition to any markers, Givens would like to see a memorial service for the deceased and believes people of all ages should participate. He said a service that can educate others on what took place at these sites would be very beneficial, not just to those alive today but to future generations.

“I want to see folks who weren’t around, you know, people my age,” he said. “I want to see Millennials, Generation Z-ers. I want to see those folks there, too, so that they can learn about that history. Because, again, you perish from a lack of knowledge. And if you aren’t educated on the history of your people, if you aren’t educated on the history of your community and your city, then how else are you going to better serve that community?”

Protecting cemeteries in the future is as important as safeguarding the legacy of the forgotten cemeteries, and Givens is working to preserve sites like Lincoln Cemetery.

“You know, I’m happy to work with the young lady, Vanessa Grey, who’s leading the effort to preserve that site,” he said. “Vanessa, myself and a few others, we volunteer our time to go out there and to cut tree limbs, to cut grass, to dig up unearthed headstones that have fallen into the ground. We take our inexperience, and we put it together to try to do the best that we can to make sure that we preserve that site.”

Yet, Givens said they need help from Gulfport, St. Pete or the county.

“It’s us pooling our monies together, making sure that we preserve the history of that site,” he said. “Now, what I’d love to see happen is, again, I’d love to see the state legislature pass a bill that would create a direct funding source to preserve lost or historic cemeteries.”

Givens believes we should hold our elected officials accountable. Through urban design and historic preservation, they do all they can to ensure the sites are maintained and preserved, ultimately memorializing those who called them their final resting places.

Click here to explore an interactive exhibit about the project.

Dr. Julie Buckner Armstrong interviewed Corey Givens, Jr. on March 22, 2021.