BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is an ongoing USF research study that addresses the erasure of historic Black cemeteries in the Tampa Bay area. Awarded a USF Blackness and Anti-Black Racism grant in 2020, it consists of faculty, staff, and students from multiple disciplines across USF St. Pete and Tampa campuses.

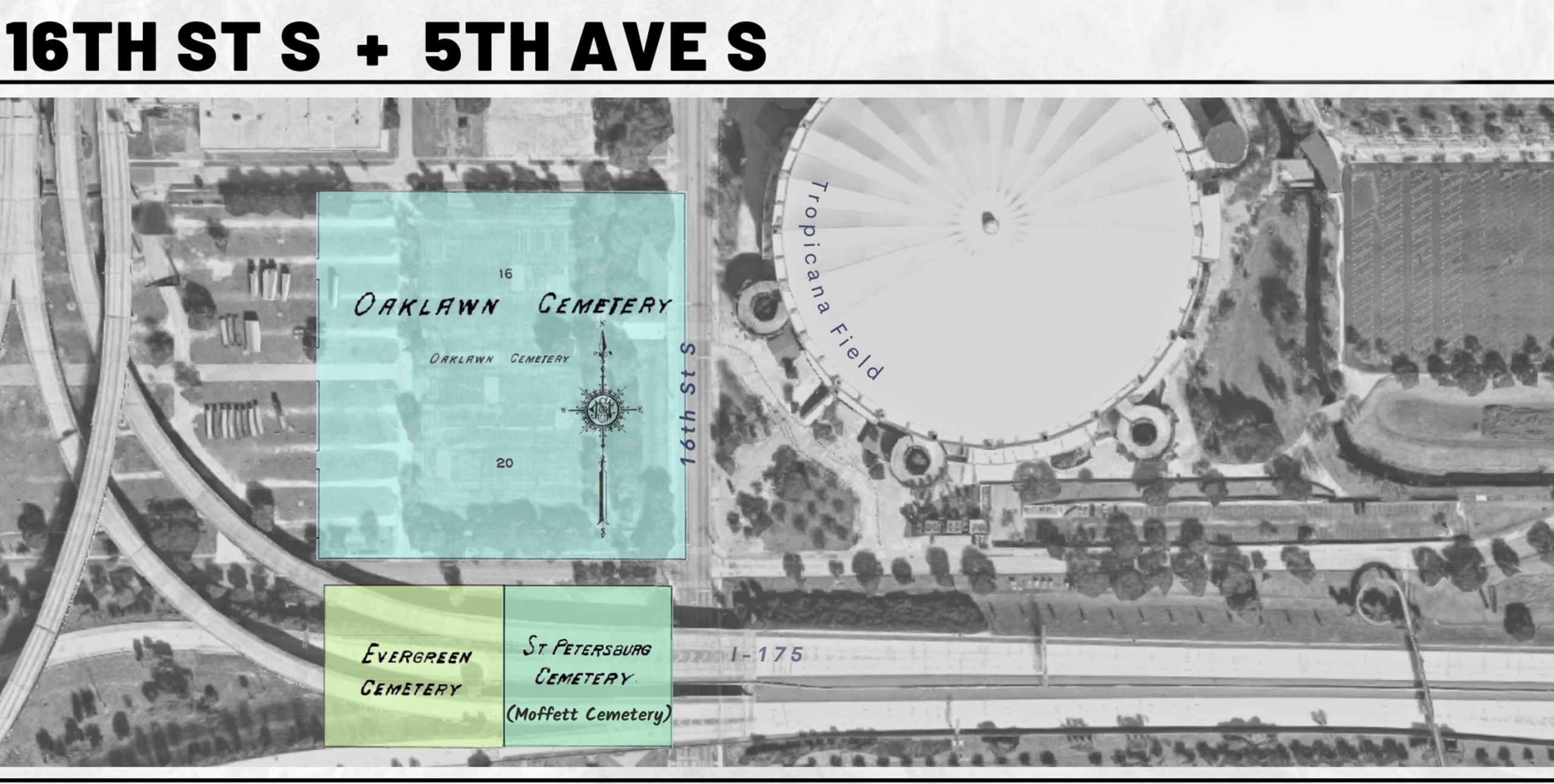

The project focuses on activities to identify, interpret, preserve, record, and memorialize previously unmarked, erased, abandoned, and underfunded African-American burial grounds in Florida, with a focus on Tampa’s Zion Cemetery (located beneath Robles Park Village) and St. Petersburg’s Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries (located beneath a Tropicana Field parking lot and I-275).

One aspect of the African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is recording oral histories of those who remember or are related to those lost to time.

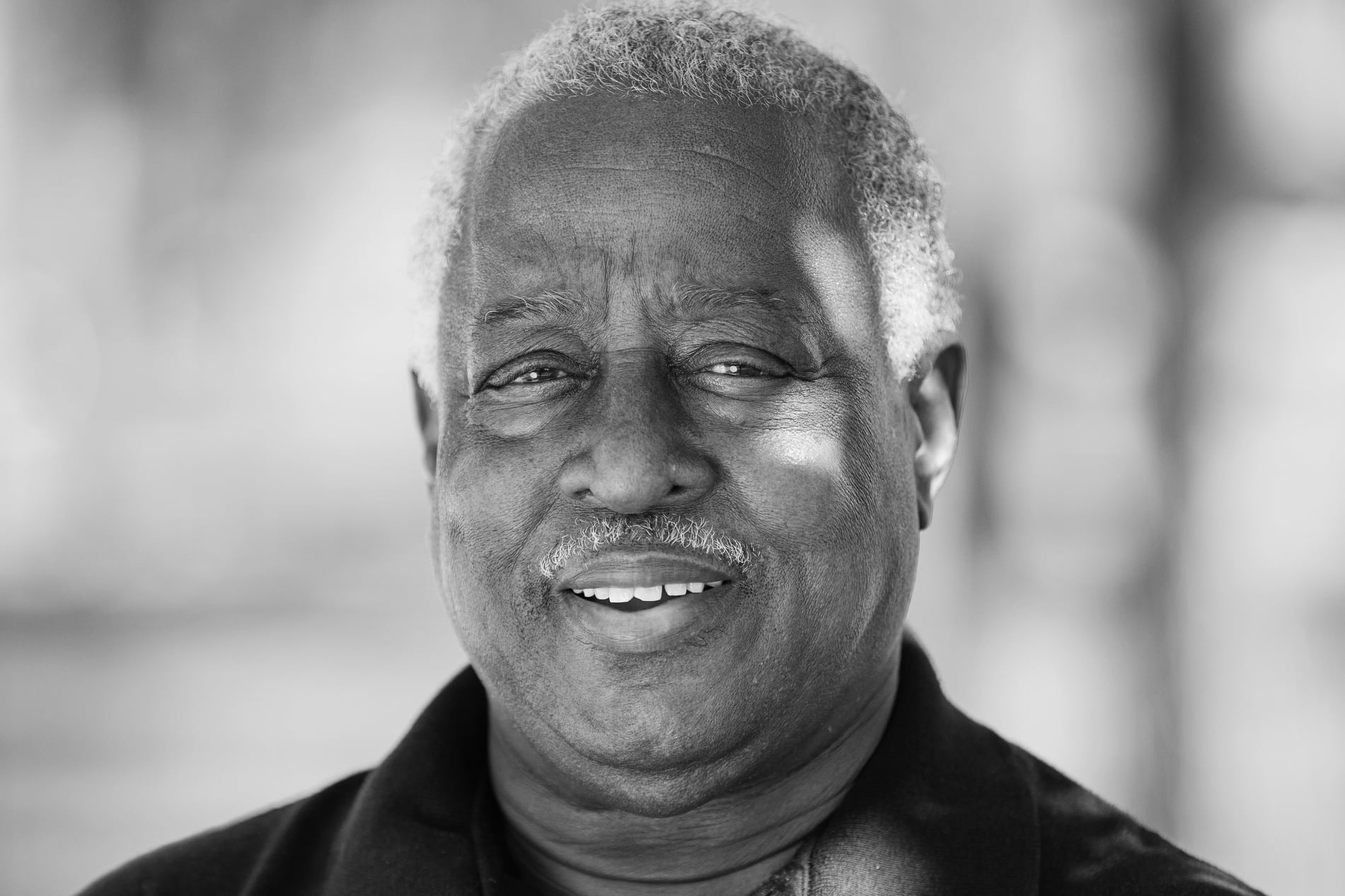

Born in 1943, Thomas “Jet” Jackson lived as a young boy at 21st Street and Ninth Avenue South in the area where Tropicana Field stands today. Years ago, there were three African-American cemeteries on those grounds. When construction began in the 1970s on I-275, a highway that would run through the city, human remains were unearthed, proving that some bodies were never moved.

“When we had to go into town, I used to run through the cemetery to get where I needed to go on the south side, to get down to Third Avenue,” Jackson recalled. “I was so afraid I would always run through the one on the south side of Fifth Avenue!”

Jackson had distant relatives buried at that cemetery.

“My family’s a real old family,” he said. “They’re the Munnerlyns, and some are buried on the south side — there were two cemeteries there — and some of our people were buried on the south side.”

Jackson said the cemetery was called Royal Palms* back then, and it later moved to Gandy Boulevard North.

He lived at the similarly named Royal Court in the 1950s, which became known as Laurel Park. He attended 16th Street Middle School and recalled some of the churches and establishments nearby, including First Baptist Church, Galilee Missionary Church, an insurance company, dry cleaners, The Weekly Challenger’s office and Welch’s Woodyard.

“There were so many Black businesses all along Third Avenue and Second Avenue and First Avenue … we lost a lot of businesses,” he said. “The interstate came and took it all out like it did the graveyards.”

When the I-75 construction project began on the grounds in the 1950s, Jackson said he saw some of the caskets being removed.

“We were nosy. We used to play basketball on the school grounds, and we’d look right over there and see everything,” Jackson remembered.

There were houses “all along that stretch,” he added. “A lot of folks lost their homes,” referring to the forced displacement of residents. Where he used to live as a youngster is now the parking lot of Tropicana Field.

Jackson noted that one building did survive; it currently houses Anchor Skate Supply on 16th Street South but was a sandwich shop way back then. Not far from there stood the Perkins house, belonging to the respected family of educators. Jackson knew the family well.

“She used to beat me!” he said, laughing. “Ms. Perkins was the English teacher at Gibbs High School. When I met them before that when I was a little kid when I worked at their grocery store. They had a grocery store across the street. And then I went to school, and she was just like a mother to me.”

As a young boy, Jackson’s memories included Little League games, the Harlem Globetrotters and baseball greats such as Satchel Paige.

“He’d come down to Campbell Park, play baseball in the field over there,” he said. “Big-name ballplayers were in there.”

Back then, it wasn’t just cemeteries that were segregated. Black athletes couldn’t stay at hotels along with their white teammates.

“In middle school, we used to go to Dr. Swain’s parties, and he used to have all the Major League players come through there, you know, that couldn’t go nowhere else,” Jackson pointed out.

After working 56 years for the City of St. Petersburg, Jackson now works part-time in funeral services. He averred that the grounds of the Royal Palms Cemetery didn’t get the care it deserved back then, as he recalled the headstones were in disarray.

“Some of them were laying down, some of them upright, some falling,” he said. “They didn’t keep the place up; they didn’t keep it up like they do today.”

When they first built the Royal Court complex, he recalled, it was a beautiful place with lush grass, palm trees and flowers.

“They maintained it pretty good at one time,” Jackson said. “Then it started doing a backslide.”

The thought of having his distant relatives’ resting place paced over by a highway and parking lot perturbs Jackson these days.

“Now I feel somewhat disturbed,” he admitted, “but before then, I didn’t pay it no attention. I didn’t pay it no attention because I really didn’t know what was happening.”

When he was young, his mother and other adults in the neighborhood would talk about the remains being unearthed for the construction but found it prudent not to speak about it too openly.

“They were concerned, but you know, a lot of them was working for folks, and they couldn’t talk too much back then,” Jackson said. “Most of them did housework, like maid work, and they just couldn’t do a whole lot of talking. They’d get fired.”

Jackson believes that the hurry-to-construct highway running through the city caused corners to be cut and graves to be paved over. The new interstate cut off corridors used by the residents and essentially spelled the end of many flourishing Black-owned businesses in the neighborhood.

Jackson believes that graves shouldn’t be disturbed, but if any remains are found, they should be salvaged and moved.

“I’m from the old school,” he said. “I don’t think you should bother; unearth the grave. But if you’ve got to unearth it, move it. That’s my belief. I don’t think you should disturb them, but it’s too late for that now.”

Click here to explore an interactive exhibit about the project.

*Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries were owned by Reginald H. Sumner, who also established Royal Palm Cemetery in conjunction with his business partner John Brown.

Dr. Antionette Jackson interviewed Thomas “Jet” Jackson on Feb. 7, 2022.

Dear Frank

This article is informative and as you know based on the work being done by the USF African American Burial Ground Team. Additional information about the project and access to the work being done by the team is published at USF Digital Commons–https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/african_american_burial_grounds_ohp/

Any additional project inquiries may be directed to Dr. Antoinette Jackson, PI, USF African American Burial Ground Project Team, via the USF Heritage Research Lab (https://heritagelab.org/). Thank-you!