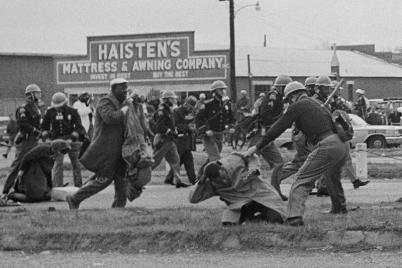

Pass-a-Grille: Sundown Town at one time. In this image, Sylvia Hilton, a white woman who spent the spring of 1911 at Pass-a-Grille, captured this image of Black people along a nearby beach. Sylvia Hilton | Gulf Beaches Historical

BY JAMES SCHNUR, The Gabber

William Bradley moved to Pass-a-Grille around 1900. At that time, the sparsely settled island had a few wooden homes, plenty of undeveloped land, flocks of free-roaming chickens, millions of sand fleas and countless mosquitoes. Bradley married, started a family, built a rooming house for visitors from the mainland and became an expert at crabbing and fishing.

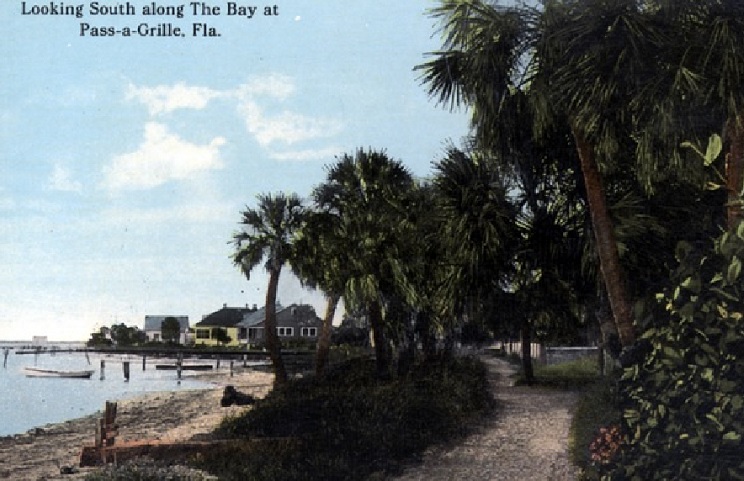

Bradley and his neighbors lived near present-day Pass-a-Grille Way and 20th Avenue. Decades before dredges sculpted Mud Key into Vina del Mar, those who settled in that area fished along Boca Ciega Bay and its many keys. They welcomed large weekend gatherings of people who visited from St. Petersburg and worked in the growing number of hotels and restaurants that opened south of 13th Avenue.

Leaving a growing community

A few of Bradley’s neighbors returned to the mainland after William D. “Bill” McAdoo opened the first bridge that connected the island with the mainland in February 1919. This narrow, wooden toll bridge spanned from Villa Grande Avenue to 87th Avenue, near Blind Pass. More of Bradley’s neighbors departed after an October 1921 hurricane ravaged the coastline.

Bradley sold his home and business in 1923. He moved his family to St. Petersburg. Soon after, crews carved roadways and built new homes at this once-remote fishing spot near where a bridge currently connects Pass-a-Grille and Vina del Mar.

Bayside pathways such as this connected Black settlements on the island with the Pass-a-Grille business district. | USF Digital Collections

Bradley did not sell his Pass-a-Grille assets to reap a handsome profit during the vibrant Florida land boom. The first known Black person to settle along Pass-a-Grille, he and his family became the last Black residents to leave the growing island community a century ago when ambitious developers and cruel Jim Crow practices forced his removal and turned Pass-a-Grille into a “sundown town.”

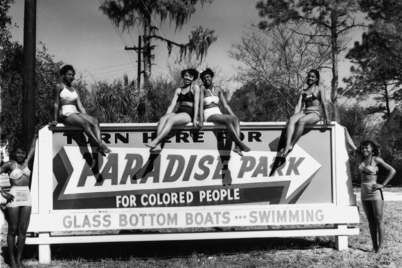

An early beachfront for Black bathers

Florida has more miles of coastline than all other states except Alaska. Despite this distinction, until recent years, Black beachgoers endured fear of immediate arrest or violent reprisals if they attempted to enjoy the surf and sand. Indeed, legal restrictions and racial intolerance created coastal “sundown towns” throughout the Sunshine State.

Although real estate boosters have promoted St. Petersburg’s waterfront since the earliest days of settlement, Spa Beach and other Sunshine City locations remained off-limits to Black bathers until the civil rights era. Similar restrictions prohibited Black people from visiting beaches at Gulfport, Clearwater and the rest of coastal Pinellas during the early and mid-20th century.

For more than 15 years, however, a then-remote section of the island three-fifths of a mile north of Pass-a-Grille’s business district became a safe enclave for Black beachgoers. The Bradleys, Gunners, and other families in this area maintained a small bathing beach for Black visitors who came to their secluded area of the island.

Bradley operated a concession stand, provided refreshments, and even rented bathing suits to visitors. He also raised hogs on an adjacent key and transported cargo for white-owned businesses before automobiles arrived on the island.

At a time when police in St. Petersburg often threatened to arrest Black bathers who set foot in Tampa Bay, this section of Pass-a-Grille offered a coastal refuge found almost nowhere else in Florida.

The waterfront of Pass-a-Grille as it appeared in 1920. | USF Digital Collections

Bradley’s beach concession welcomed mainland visitors to Pass-a-Grille years before many other fabled beach destinations opened during the Jim Crow era. Long before American Beach offered a haven on Amelia Island in northeastern Florida, Black beachgoers swam and fished along a portion of Pass-a-Grille.

A known and respected neighbor

Although William Bradley lived on the other side of thick mangroves and sea grape trees that separated him from Pass-a-Grille’s business district, white residents relied on his services and ingenuity during the community’s early years. George Lizotte, the island’s first hotel operator, called Bradley “the colorful magnate of transportation on the island.”

Bradley brought a mule and wobbly wagon to the island on a simple barge sometime before 1910. Soon, he used this early form of transportation to carry supplies, remove refuse and provide firewood for cooking. The boarding house Bradley built offered shelter for Black workers employed at nearby white hotels before McAdoo’s bridge opened.

Despite his involvement in Pass-a-Grille’s early development, the only notable mention of the man known as “Old Bradley” in early narratives involved an unfortunate incident. During the 1910s, St. Petersburg resident Elmer “Ermee” Ermatinger hired a Gulfport barge to bring his REO Runabout to Pass-a-Grille. The first automobile ever driven on the island, this two-cylinder vehicle generated a lot of smoke and noise as Ermatinger drove it on the firm sand during low tide.

One day, as Bradley hauled supplies along the beach, Ermatinger’s loud Runabout scared his mule. As the frightened animal tried to escape, the wagon flipped and knocked Bradley to the ground.

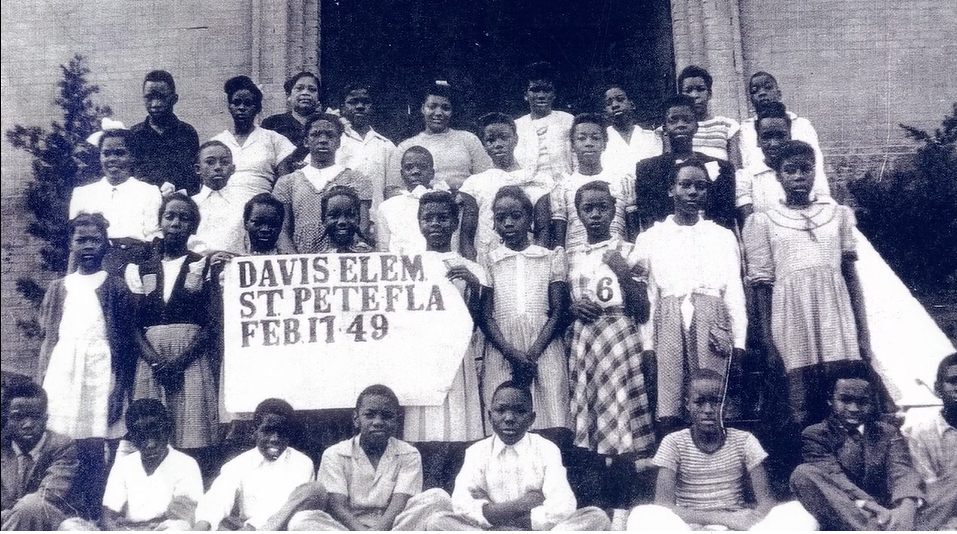

An inconvenient education

Pass-a-Grille’s first school opened in 1912. Unfortunately, Bradley’s children and other Black youth living on the beach could not enroll at this whites-only facility. These elementary-age pupils had to take a boat to Gulfport. They transferred to a streetcar to reach Davis Elementary, a school in the Gas Plant district that opened in 1914.

St. Petersburg’s Davis Academy, later named Davis Elementary, served as the closest school for Black children who lived in Pass-a-Grille.

These children usually lived with Black families in St. Petersburg during weekdays. This allowed them to avoid the long commute between Pass-a-Grille and their school. Bradley and other Black parents on the island worried about their children’s safety in St. Petersburg, especially after the November 1914 lynching of John Evans in that city and increased Ku Klux Klan activity throughout Florida.

During the 1910s, Pass-a-Grille offered a somewhat safe coastal haven in a state increasingly consumed by racial hate.

Born on the island in December 1912, Julius Bradley entered the world at a time when his father was a respected member of the beach community. Julius and his siblings attended Davis Elementary before the end of the decade. By the time Julius entered Gibbs High School, things had profoundly changed in his “hometown.”

Keeping sands white and dry

Pass-a-Grille was incorporated as a municipality in June 1911. John J. Duffy, the first mayor, came to the area from West Virginia. Similar to the popularity of many Florida beaches during spring break today, Pass-a-Grille became a popular destination for partygoers by the late 1910s.

Black people were only permitted to use the bathing beach at the South Mole on the east end of First Avenue South, now known as Demens Landing.

The 18th Amendment and the federal Volstead Act criminalized the consumption of alcohol. Soon after, an intoxicating number of drinking parties took place in remote areas along Pass-a-Grille during the 1920s. In March 1922, Duffy declared war on drunkenness in his city. He told a Tampa Tribune reporter that “young (white) girls and women from St. Petersburg” were the main offenders.

Duffy pledged to arrest, fine, and have the names of these offending day trippers published in local newspapers. Instead, he and other city leaders targeted the island’s shrinking Black community. For example, officers raided the Pass-a-Grille home of a Black woman in August 1922. They arrested her for the unlawful possession of “intoxicating liquors.”

Meanwhile, white beachgoers’ drinking parties and gambling gatherings continued largely unabated.

Moving to the mainland

William and Mary Bradley moved their children to St. Petersburg in 1923. They lived in a small home at 720 17th St. S., now part of the John Hopkins Middle School campus. William traded his crab traps for various jobs as a laborer.

Born on the island in December 1912, Julius Bradley entered the world at a time when his father was a respected member of the beach community.

Julius came of age when Black people were expected to remain in their segregated St. Petersburg neighborhood after sundown. He graduated from Gibbs High School. He later taught there, as well as at Union Academy in Tarpon Springs and 16th Street Junior High. This school once sat on the land now occupied by John Hopkins Middle School.

After the Bradleys moved, Klan gatherings occurred more frequently at Pass-a-Grille. More than 200 new Klan members were initiated along the beach during the early summer of 1924. Newspaper reports from the time claimed that a Jan. 9, 1925, Klan ceremony at Pass-a-Grille “drew several thousand persons from St. Petersburg.” A month later, the Klan held a “naturalization ceremony” near the Pass-a-Grille Casino.

Black workers in Pass-a-Grille businesses had to commute from the mainland for decades after the Bradleys left in 1923. During the mid-1930s, a Black couple named Tom and Idella briefly lived in a small wooden cottage near Eighth Avenue. Hostile conditions soon compelled these domestic workers to leave.

Although they portray only a brief snapshot in time, federal census records illustrate the disappearance of Pass-a-Grille’s self-sustaining Black community. In 1910 and 1920, census enumerators recorded the names of Black families who lived in their own homes.

During the 1930 and 1940 census campaigns, only a handful of Black people employed as live-in “servants” at private residences appeared in the records. Many of these individuals also had family in St. Petersburg that provided them with a permanent residence. By 1950, only white servants lived on the island.

An important legacy

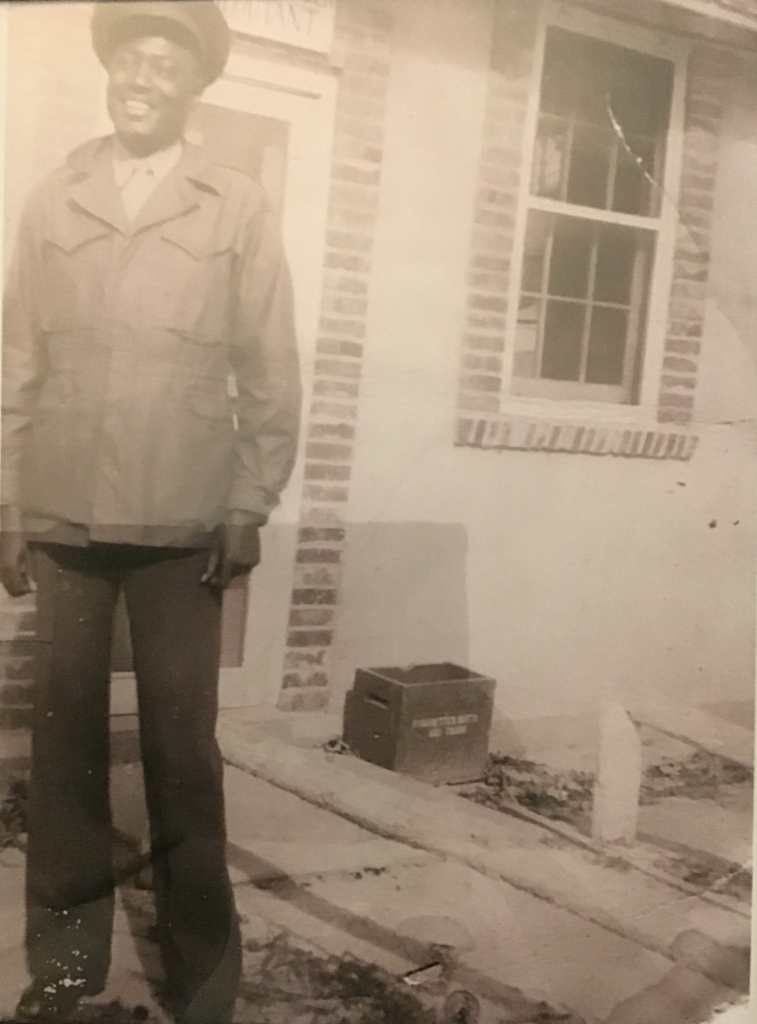

Despite their departure from the island a century ago, Black residents of Pass-a-Grille contributed to our area’s history. During World War II, Julius Bradley became a Montford Point Marine, the earliest Black people to desegregate the U.S. Marine Corps. Julius Bradley passed away at Bay Pines in 1991 without any recognition of his service as a Marine.

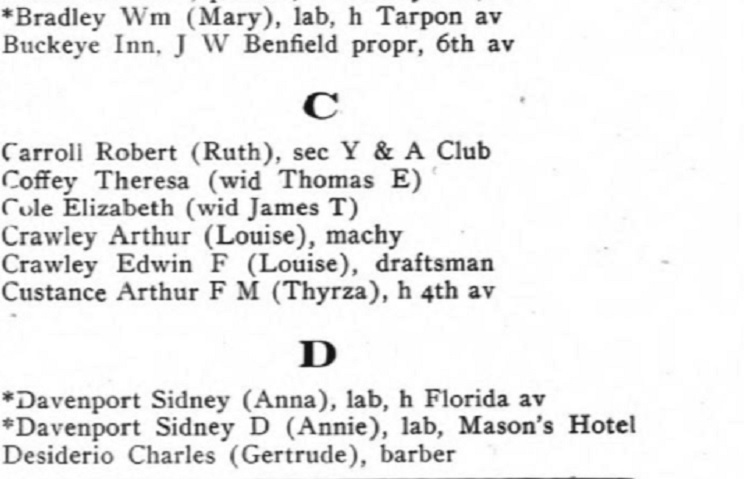

This portion of Pass-a-Grille’s 1914 city directory identified William Bradley as a laborer. The asterisks were used to denote non-white residents. | Clearwater Public Library

On March 27, 2021, Julius Bradley’s family was presented his Congressional Gold Medal along with a certificate of recognition from President Barack Obama.

Few records remain of Pass-a-Grille’s once-thriving Black settlement. Shining light on the years before the island became a “sundown town” preserves the legacy of a community worth remembering.

This article was originally published in The Gabber on July 6, 2023.