BY J.A. JONES, Staff Writer

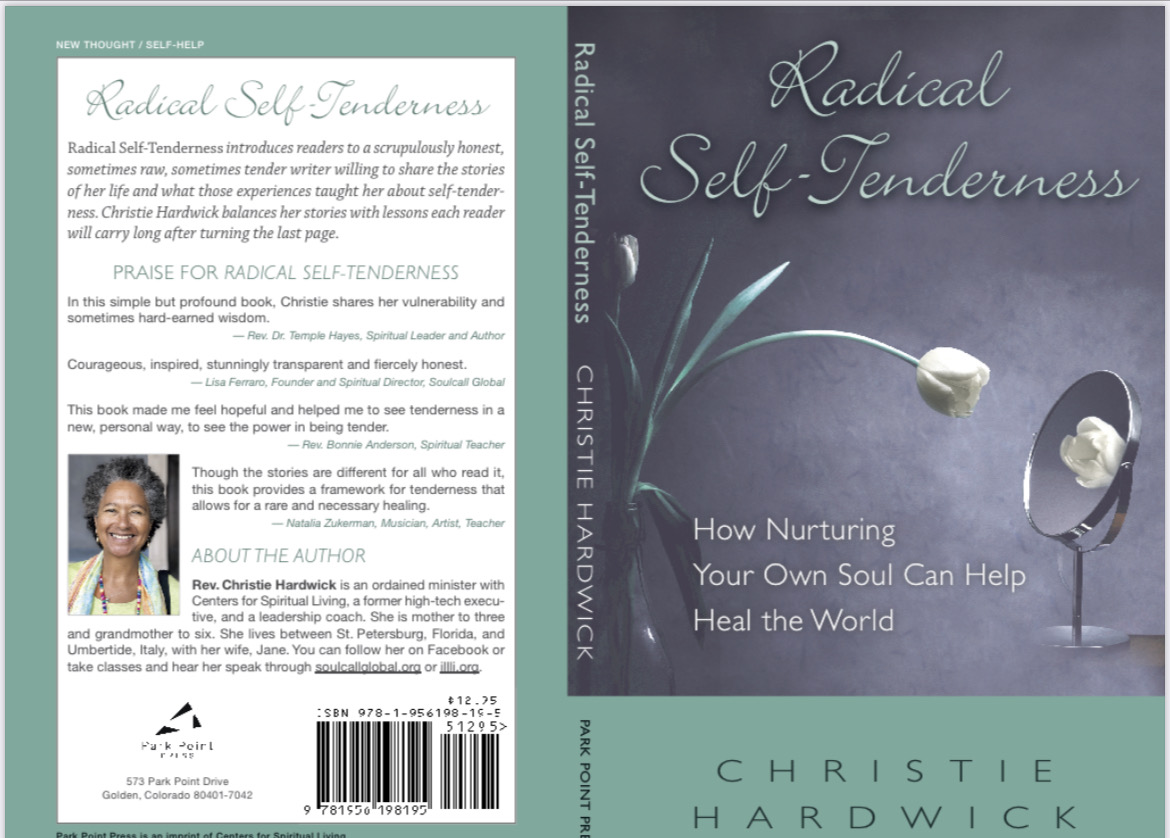

ST. PETERSBURG — Rev. Christie Hardwick’s book, “Radical Self-Tenderness: How Nurturing Your Own Soul Can Help Heal the World,” is a personal story of self-healing in process, specifically healing by learning to be tender with ourselves.

“Self-tenderness,” said Hardwick, “is not the same as kindness. It’s not even just the same as vulnerability.” And, she added, “It’s not the same as self-care. It’s something a level beyond that, in terms of the level of vulnerability — the level of self-care.”

Self-care has become a larger community talking point as the mental health of Black Americans has been hammered in the last several years by cultural events and attitudes that feel like personal and political attacks. Black Floridians may feel it more than others as legislation carrying anti-Black sentiment continues to stamp out gains made in decades past.

While not explicitly written for any group of people, Hardwick’s book feels especially important for communities feeling the harshness of America’s changing political, social and economic landscape post-COVID.

“I wanted to help people take their power back because there’s so much going on in the world that makes you feel like you can despair. [Ask yourself] What can I do? It’s so big; how can I solve [anything]?” Hardwick shared.

Tenderness is a concept that may be foreign to many people raised in environments where the idea of being “strong” and “resilient” do not seem to go along with the definition of tenderness. Hardwick, who also holds workshops around radical self-tenderness, noted that in each workshop, questions arise for attendees on whether being tender with themselves equates to weakness.

Hardwick understands where this comes from and helps attendees share an idea they have about tenderness that causes them some conflict inside, and she said this idea of tender, meaning weak, always comes up. People ask themselves, “If I’m tender with myself, that means I’m weak, and I’m not being hard enough on myself, and I’m not holding myself to a standard,” she noted.

Instead, she encourages them to “take inventory” and ask themselves if there is any benefit to having that idea. While the upside may be “working really hard and getting a lot done,” the downside is often a kind of self-harshness that is counterproductive.

“I have met more people in our Black community who are so worn out, who are giving more than they have and believe that that’s what they must do. In my workshop, these same people go through the process of recognizing the cost of this constant pushing and constant giving and no replenishment,” she relayed.

The point is to take a breath and a step back, she continued, “to see that actually I could serve my purpose in an even greater way — if I was tender with myself. Then it becomes not a weakness, but a way of being stronger in your purpose … because you’re being more tender with the vehicle.”

The vehicle is ourselves, which Hardwick refers to as the conduit and body that God works through. Asking her attendees: “If you’re wearing yourself out, and not caring for this body, temple, and not caring for this person…how much can you [do]?”

Maress Scott, founder and executive director of the nonprofit Quis for Life, testified to how impactful Hardwick’s workshop and book were for him. Driven by the loss of his son Marquis and his need to lift up his family and the community, Scott noted that he has felt the non-stop pressure begin to gradually make room for a more impactful way of operating since he’s stopped to consider the idea of radical self-tenderness.

While he had never even conceived of the idea, Scott said the first chapter of Hardwick’s book, “How Can I Be Terrified of Tenderness,” immediately struck a chord; it was an eye-opening realization that he had never considered, but he realized at once it somehow related to his fears of being alone, abandoned and responsible for his own healing journey.

During Hardwick’s training, he had another epiphany. “As we went through the training, I realized that my preconceived idea was that I was responsible for everybody in the room. But listening and going through the training, I realized that I was helping so many people that I was denying them the opportunity for self-advocacy.”

Beginning to listen more closely to what Hardwick what saying, Scott realized he was also doing those around him a disservice by doing too much. “I was denying them the opportunity to gain strength from the experience they went through, but more importantly denying myself in helping everybody else; I had subconsciously told myself I wasn’t worthy” of having his own healing experience.

Rev. Christie’s book shares her story of acknowledging how difficult the journey to self-tenderness is and, along the way, gives readers a picture of how they can find their own moments to start that journey. She noted that sharing “intense and intimate details of my life was in order to invite people no matter what their circumstances were, or what their particulars were of their story, there’s still this thing that you can do that relates to you — and you alone — that can shift things.”

Hardwick’s book traces her journey from learning painful truths about her biological parents, through an unhappy marriage and career success during a deep depression, to finding her identity and sexual being. It’s a stark and truthful read that challenges readers to seek self-understanding as to our personal histories and what might make self-accusation, negative self-talk and lack of self-compassion easier than she feels we all need more of — self-tenderness.

“If you are tender with yourself, and you cultivate this tenderness inside you, whatever you’re cultivating in there is something that then is broadcast by you just by your presence. And this world needs more tenderness. I just want people to know that they are powerful and that their own tenderness has power.”

Hardwick said that she continues to receive notes from folks around the country about how considering radical self-tenderness has “been illuminating. They often mention that they had never considered applying tenderness toward themselves — especially men.”

Hardwick can be reached through messenger on her Facebook page for those interested in virtual self-tenderness coaching sessions. She will be in person in St. Pete next January, offering new in-person workshop experiences.

You can purchase “Radical Self-Tenderness” at Tombolo Books, 2153 First Ave. S, St. Petersburg; an audio version will be released soon. Learn more about Rev. Christie Hardwick at inspirationgatherings.org.