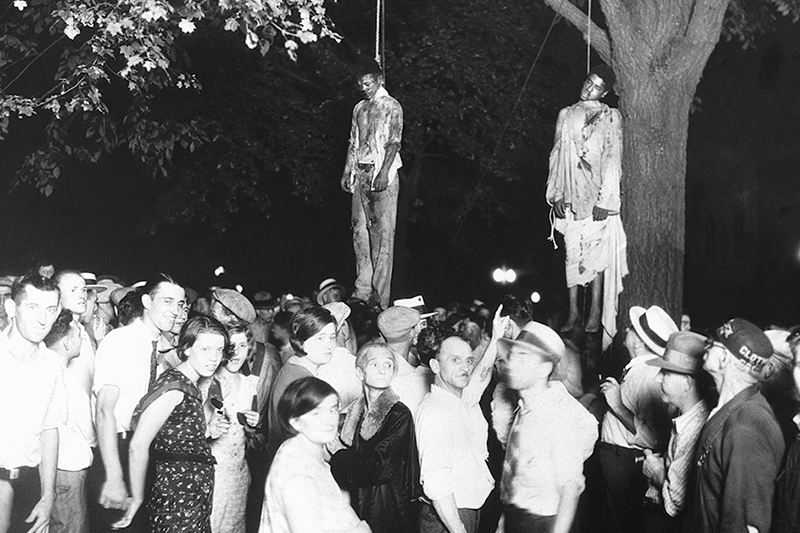

The lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, 1930

By Jennifer Gamble-Theard

To speak of lynchings and incarcerations of African Americans may seem a bit depressing or even a little stiff or overly serious to some. Such topics can cause frustration or push back in conversations.

Some might say that lynchings are of a bygone era and suggest looking forward to the future. Others may focus on post-slavery to current times regarding excessive incarcerations, suggesting that perceived criminals must be punished, but never mind the details.

Both lynchings and incarnations have had a tremendous impact on the lives of many African Americans youths. Every generation of African Americans had/have been aware of men or women, past or present, whose lives were destroyed or halted due to the systematic punitive controls of black people.

Far too many black voices were silenced from 1877 to 1968 with almost 4,000 lynchings that occurred throughout the United States, both north and south. The majority of lynchings took place in the south, carried out by crazed mobs of white Americans who felt that the institution of slavery for economic purposes should have never ended.

They wanted to make a point that blacks must always stay in their place — beneath them. To a lesser degree, northern states also used lynchings, but more to control blacks for political, employment and voting purposes.

In the south and north as well as east and west, lynchings were used as a method of social and racial domination meant to terrorize black Americans into submission, and into an inferior racial caste position characterized by skin color.

Fast forward to current times in America, we may not hear too much anymore of lynchings, but wounds of 21st century America are fresh from mass incarceration of young African-American men, as well as a smaller but growing number of black women.

There has been a 500 percent increase in the number of inmates over the last 40 years, precisely taking root after the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. According to statistics, the crime rates in the United States have been decreasing, yet the percentage of black inmates continues to increase.

African Americans make up nearly 1 million of the 2.3 million persons incarcerated, which is nearly six times the rate of whites. This estimates that one in three African-American men will experience prison sometime in his life.

As a result of present day incarceration practices, black voices are again being silenced in a different way. In 34 out of the 50 states in America, those individuals on parole or probation cannot vote.

In 12 states, a felony conviction means never voting again. Also, prior incarceration can and or will affect one’s ability to secure certain government benefits, or the ability to get a job.

Lynchings and incarcerations are interwoven together as social obstructions for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness for the collective African-American experience. Many African-American communities were, and still are, effected from the scars left by the absence of those who were brutally killed from lynchings.

As well, some communities of color struggle on a daily basis from the negative impacts of social stigmas and non-participation within American institutions. Full interaction with government decision-making or advances in economic growth can become unattainable for those with a past connection to the U.S. prison system.

As a people of the African diaspora, our voices must not be silenced. It is necessary that we must become aware of our history and of how the United States Constitution specifically affects the outcome for those from black communities who may not fully understand the consequences of counterproductive actions.

As slavery formally ended, the 13th Amendment was added to the Constitution in 1865. It’s a very interesting statement that says “no one can be enslaved or under involuntary servitude except if they are convicted of a crime.

In plain and simple language, slavery still exists for those who are convicted of crimes. As a figure of speech, the prison industrial complex now and always existed in the United States — meaning that slavery evolved into a form of labor subordination and exploitation.

This was especially seen in the prison chain gang system in the south were young black boys could be herded into prisons for non-criminal behavior such as standing on a sidewalk or any minor action considered deviant by those in power. Families, who thought that they were free, could lose their sons to another form of slavery.

The prison population today is vulnerable to servitude as a punishment for crime. This can be seen in “for profit-prison” systems where prisoners work for little or no money, and corporations that use prison labor have the advantage to advance corporative profitability.

Whether there are more prisons or fewer lynchings, it’s crucial to realize how important it is to help keep our youth informed about crimes as life’s obstacles and the outcomes of “slavery by another name” called incarceration.

To continue with more exact and engaging information about lynchings and mass incarceration, I recommend two books that are well worth reading:

University of South Florida, St. Petersburg professor and noted author Julie Buckner Armstrong’s “Mary Turner and the Memory of Lynching.”

Well known civil rights advocate, Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.”

Also, please be aware of “The National Memorial for Peace and Justice” opened on April 26, 2018. This is the nation’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence.

Located in Montgomery, Ala., the St. Petersburg ASALH Branch is planning a trip there in Oct. of this year. Please be in touch if anyone is interested in attending.

Other noteworthy information is about St Augustine’s Episcopal Church, which is spearheading an effort to locate lynching sites here in the St Petersburg area.

Jennifer Gamble-Theard, M.Ed. is a retired Pinellas County educator in the study of history and language. She is also the historian for the St. Petersburg Branch of ASALH.