by Keisha Bell

Are you the type of person to do something about racial injustice or are you a “go-along-to-get-along” type in the face of racism?

At times, the fight for racial equity can seem overwhelming. Still, what is your contribution for righting civil racial wrongs—not only for yourself— but for those generations coming after you?

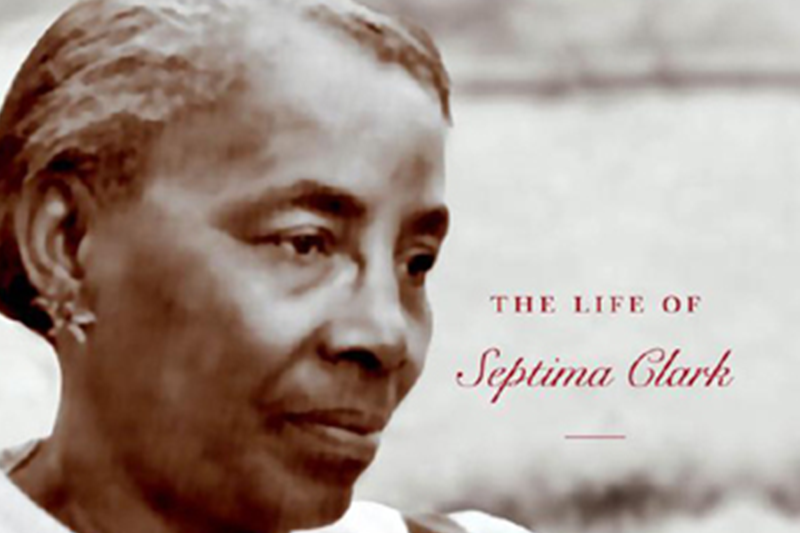

Meet Septima Poinsette Clark. Clark was an educator and a civil rights activist.

Due to discriminatory laws and practices in South Carolina, Clark was barred from teaching in public schools in Charleston because she was African American. As a result, she landed a teaching position in a rural school district in Johns Island in Charleston County.

It was during this time that Clark developed innovative methods to rapidly teach adults how to read and write using everyday items such as the Sears catalog.

Not only was Clark denied an opportunity to teach within the city of Charleston, but she also was impacted by the gross discrepancies in pay as well as the student-to-teacher classroom ratio that existed between her school and the white school across the street.

Because of these inequalities, Clark became actively involved in pay equalization for teachers. In 1919, her pay equalization work, as well as, her experiences of growing up in a racially discriminatory Charleston motivated her to participate in the Civil Rights Movement.

Clark returned to the city of Charleston and took part in her first political action with its NAACP chapter. She led her students and got 10,000 signatures in one day to allow black principals at Avery Normal Institute, a private school for black students. In 1920, Clark enjoyed her first legal victory when blacks were given the right to become principals in Charleston’s public schools.

In 1945, Clark worked with Thurgood Marshall on a case that was about equal pay for white and black teachers led by the NAACP in Columbia, S.C. Their work was victorious.

In 1956, Clark obtained the position of vice president of the Charleston NAACP branch. Interestingly, that same year the South Carolina legislature passed a law banning city or state employees from being involved with civil rights organizations. Clark refused to leave the NAACP. As a result, she was fired from her job by the Charleston City School Board and lost her pension after 40 years employment.

Not surprisingly, no school in Charleston would hire her. She did, however, find support from a black teachers’ sorority that held a fundraiser for her benefit, but its members feared losing their jobs and all refused to have their picture taken with her.

[Note: Later, Clark won her fight for the reinstatement of her pension and back pay. In addition, she served two terms on the Charleston County School Board. Who would have predicted that?]

Everyone will not make the same decision that Clark made if faced with conscious awareness about the overt racism that affects their livelihood. That expectation is unfair. Some people will assist from “behind the scenes” as did the black teachers’ sorority.

Keisha Bell