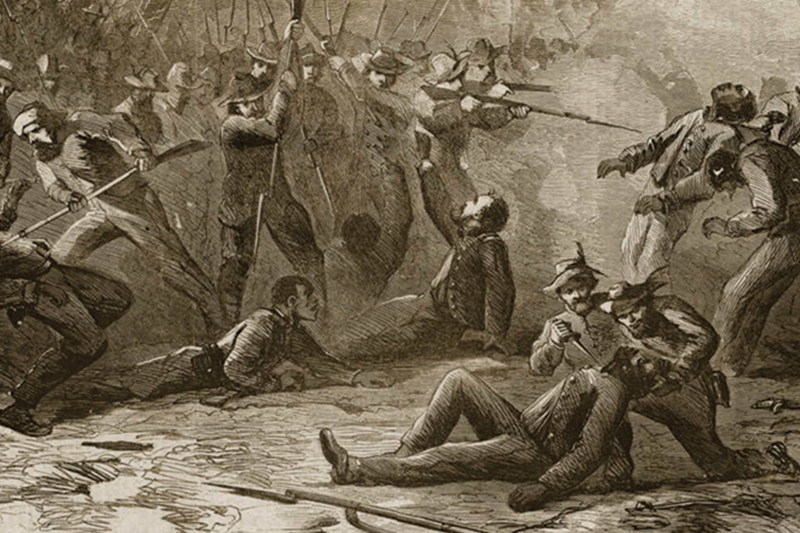

Fort Pillow Massacre as depicted by “Harper’s Weekly,” April 1864.

BY JACQUELINE HUBBARD, ESQ., ASALH President

During the Civil War, racism placed black soldiers in extreme peril. By 1862, black soldiers comprised approximately 10 percent of the Union Army, or nearly 180,000 black troops.

Author Drew Gilpin Faust wrote in her highly acclaimed book “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War” that black troops represented an “intolerable provocation” to the Confederate Army. She posits that if they permitted black troops to serve as soldiers, this would suggest that their whole theory of slavery was wrong.

The terrifying actuality of a force of armed black men seemed equivalent to a slave uprising launched by the federal government against the South. White southerners feared and detested black troops. Confederate troops regarded black Union troops as “devils.”

There were many atrocities committed against black troops during the Civil War, but perhaps the most horrible was the Fort Pillow Massacre. The bloodbath occurred in April 1864 when Confederate Officer Nathan Bedford Forest’s men stormed Union troops at Fort Pillow in Tennessee, overtook the fort and killed nearly all of the 300 black Union troops rather than taking them as prisoners of war.

Black troops were killed as they tried to surrender; they were killed as they ran away; they were killed as they lay in hospital tents; they were killed in groups, and they were killed individually all by Confederate troops.

Another one of many atrocities committed against black Union troops includes an incident after the Battle of the Crater in 1864, where Faust said wounded black soldiers begging for water “were killed by bayonet thrusts.”

A subsequent order was relayed to Confederate troops “to kill them all,” which Faust said the command was willingly obeyed. General Robert E. Lee, only a few hundred yards away, did nothing to intervene.

The Confederacy declared by April 1863 that it would make no black soldiers as prisoners of war, dictating that they should be killed instead. In “From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans” by John Hope Franklin and Alfred Moss (6th Ed.), the authors stated that after 1862, “Hardly a battle was fought to the end of the war in which some Negro troops did not meet the enemy.”

Southerners were outraged at the North’s use of black soldiers. From the beginning of hostilities, the Confederate leadership had to decide whether to treat black soldiers captured in battle as slaves in insurrection or, as the Union insisted, as prisoners of war.

Shortly before the massacre, Union Gen. William T. Sherman was assembling troops in Chattanooga, Tenn., in anticipation of his drive on Atlanta. Forrest, who had already earned a reputation as a violent commander who often issued “surrender or die” ultimatums to Union troops, hoped that his raid on Fort Pillow would halt General Sherman’s progress.

Fort Pillow held a force of between 500 and 600 troops, consisting of unionist southerners, Confederate deserters and about 300 black soldiers. Forrest had 1,500 to 2,500 Confederate cavalrymen who surrounded the Fort on the morning of April 12, 1864.

Confederate and Union witnesses stated that Union soldiers, most of whom were black, were gunned down after attempting to surrender. Many more were shot as they fled. Between 277 and 295 Union troops were killed, with only 14-18 Confederates losing their lives.

Though the Union troops surrendered and thus should have been taken as prisoners of war, they were killed. This refusal to accept black troops as prisoners of war was inhumane and barbaric. The Confederates’ refusal to treat black troops as traditional prisoners of war infuriated the North and led to the Union’s refusal to participate in any further prisoner exchanges.

Allegations of the massacre were made immediately following the battle. A congressional committee was asked to investigate the matter to ascertain what had happened. The congressional committee determined the Fort Pillow Massacre was a massacre without parallel.

Black Union troops used the massacre at Fort Pillow as a rallying cry as they continued their battle for freedom. Ultimately, the Union troops defeated the Confederacy in 1865, ending the Civil War.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.