‘The Weekly Challenger’s’ Jake-ann Jones delves into revolutionary Florence Tate’s life, covering her political work, career, and crippling bouts of depression.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Florence Tate, pioneer journalist, civil rights activist, and survivor of clinical depression, had quite a life story to tell. Luckily, she leaves behind a memoir, co-written with Jake-ann Jones, which documents her rich life.

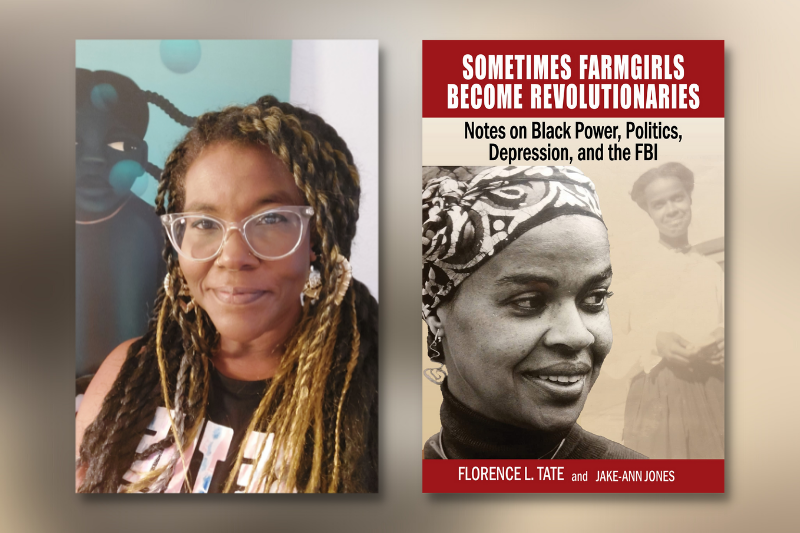

Jones discussed the book “Sometimes Farmgirls Become Revolutionaries: Florence Tate on Black Power, Black Politics, Depression and the FBI” at Tombolo Books on Feb 22. Jones has taught at several universities, is the managing editor of The Weekly Challenger, a playwright, and a screenwriter.

Moderating the event was Dr. Brittany Peters, a licensed clinical social worker who owns and operates the Center for Wellness and Clinical Development.

Born in 1931, Tate spent her earliest years in the Jim Crow South before becoming the first Black female reporter for the Dayton Daily News in Ohio, where she was active in the Dayton chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and founded several local civil rights organizations.

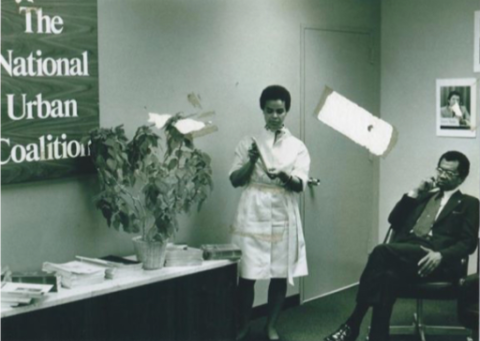

She became a player in Black activism, organized marches, and served as communications director for political organizations such as the ALDCC (African Liberation Day Coordinating Committee) and National Urban Coalition.

In the 1980s, Tate served as communications director for Marion Barry during his first year as the mayor of Washington, D.C., and worked for candidate Rev. Jesse Jackson as press secretary when he made a historic run for the White House in 1984.

Tate relocated to Sarasota to write her memoir and Jones recalled that they grew close before her death in 2014 “like girlfriends.”

“She was extremely youthful, even though she was 79 when I met her and 84 when she passed,” Jones said. “She was like a girl; she laughed, and she giggled,” adding that they would go shopping and to the movies together.

During their initial friendship, Jones knew Tate was an activist, but it came as a surprise to even her that the FBI had a file on Tate. Intrigued by this, Jones asked her if she’d written a memoir, and though it was something Tate had wanted to do, it only really took flight when Jones got involved.

Florence Tate, left, and Jake-ann Jones became close friends during the process of writing Tate’s memoirs.

She examined Tate’s thick FBI file and dismissed it as “pages and pages of crap,” as there was mention of radical Black groups in it but no concrete tie between them and Tate herself.

“They couldn’t find any relationship to these things, but they stuffed it in her file anyway,” Jones said.

The FBI, then led by J. Edgar Hoover, went to extreme measures to deter Tate from her career in activism. They attempted to disrupt her marriage by trying to convince her husband that Tate had been carrying on an affair with Stokely Carmichael, the controversial and outspoken civil rights leader.

Tate, a wife, and mother of three, also suffered from severe, lifelong depression and resorted to electroconvulsive shock therapy — which sends shock currents through the brain — to cope with it. Jones admitted that she had never known anyone who had taken that extreme path for a remedy.

“She did it once every seven years for many years,” Jones said and noted that Tate had believed the shock therapy may have even caused her to forget people and events in her life.

Peters added that though this treatment is not as widely used as before, it is still used for individuals who may have found that their depression is not responding to medication or other treatments.

Jones witnessed Tate’s depression firsthand, as she recalled watching her lying on her couch, sobbing. Though Tate tried to reassure her friend that she’d be all right, Jones remembered it was difficult to watch. Jones remarked that her depression was a part of her life until she died.

The book’s initial chapters deal with Tate’s traumatizing childhood, which included her mother abandoning her when she was only three years old, only to come back in and out of her life in the ensuing years. Her father left a few years after her mother, and Tate was left with her great aunt and uncle on their farm. Tate fostered resentment for years afterward and didn’t truly find some kind of peace until she reached middle age with the help of psychiatry.

The shared experiences of Tate and others like her served to bring them all together as they bonded over their struggle for civil rights, Jones pointed out.

“She spoke about those memories like they were the best time of her life,” Jones stated. “Those are the people that are close to her,” adding that Tate had more than 1,000 friends on Facebook, as she and her fellow activists kept in contact over the decades.

Referencing a passage in the book, Peters said that Black power to Tate was a way “for Black people to come together, to improve our communities and make decisions.”

“She was like a radical old lady, even when I met her!” Jones recalled. “I could see the passion. She was a radical; she’d hang out with all those radical cats, you know, and they were hardcore. I mean, for them, it was life or death.”

Jones said she has now adopted a phrase that Tate used, “a luta continua,” which means “the struggle continues.”

“All we can do is fight; that’s all we can do,” Jones said. “We have to fight the negativity. We have to fight the oppression. We have to fight to protect our children and to teach our children.”

When Tate expressed doubt that people would care enough to read about her story, as she viewed herself as a relatively unimportant player in the struggle, Jones had a ready answer: “Florence, you are such an inspiration and the times that we’re coming into, we need these kinds of books! I was like, ‘This will be a guidebook!’ For all the horrible things that she went through, she did amazing things; she had amazing experiences.”

In 1974, now in her 40s, Tate traveled to Africa during the Sixth Pan-African Congress (6PAC) held in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. There she met several Angolan revolutionaries, and when she returned to the United States, she threw her support behind the Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), when many of her fellow activists supported the popular Movement of the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). This group went on to govern independent Angola, which made her persona non grata among the Black Power Movement community in this country.

“She basically got blackballed here,” Jones said. “It was very negative for her because all of her people who she had worked with for 20 years and come up alongside them in the Civil Rights Movement, the American Black Power Movement, were now against her.”

In the 1980s, Tate served as communications director for Marion Barry during his first year as the mayor of Washington, D.C., and worked for candidate Rev. Jesse Jackson as press secretary when he made a historic run for the White House in 1984.

When Jackson referred to Jews as “Hymies” and to New York City as “Hymietown” in January 1984 during a conversation with a Back Washington Post reporter and Barry was sentenced in 1991 for possession of crack cocaine, both fell out of favor with the mainstream media of the time. Tate noted in the memoir that the press let loose “with a certain viciousness that is reserved for Blacks.”

“‘What happened with Marion was a blip on the radar,’ that’s what she would say,” Jones said of Tate. “She said, ‘I looked at his long-term dedication to the Black cause.'”

After Jackson lost his bid for the presidency, Tate was a political communications consultant and active organizer for political causes in Washington, D.C., until she died in 2014.

You can pick up a copy of “Sometimes Farmgirls Become Revolutionaries: Florence Tate on Black Power, Black Politics, Depression and the FBI” at Tombolo Books, 2153 First Ave. S, or on Amazon.

To reach Frank Drouzas, email fdrouzas@theweeklychallenger.com