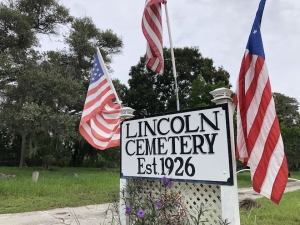

City officials issued condemnation orders for three Black cemeteries in 1926, (Evergreen, Moffett, and Oaklawn) prohibiting any additional burials, and called for the removal of bodies already buried at these locations. Some bodies were relocated to the newly established Lincoln Cemetery. Photo by Photo by Shelly Wilson

BY JAMES A. SCHNUR, The Gabber

Lincoln Cemetery’s troubled history

GULFPORT — In late 2015, Gulfport resident Vanessa Gray took more than a passing interest in a nine-acre cemetery she’d been by many times in her life. A 22-year-old restaurant worker at that time, she visited a place that appeared to be in disrepair, full of trash that buried the memories of the souls resting on this site.

She was not the first to notice the poor upkeep at Lincoln Cemetery. City officials in Gulfport had dispatched work crews to mow grass and remove debris from this neglected burial ground for years. As the cost of this upkeep grew, the city placed code enforcement liens on the property. Attempts to bring the cemetery into compliance were futile, at best.

Others also took notice of Lincoln’s condition. Members of the Gulfport Historical Society began expressing their concerns years ago.

Taking ownership of the situation

Gray, who is white, started to spend time at Lincoln Cemetery. She removed garbage, uncovered tombstones buried by the sands of time, and paid her respects to a place some had forgotten, and others had ignored. Her efforts initially won praise from city leaders, people with family members buried there, and the larger community.

A 1943 aerial map of the site of Lincoln Cemetery. Courtesy of the University of Florida.

The volunteer efforts of Gray and the others who joined her improved the cemetery’s condition. The City of Gulfport expressed its appreciation in an August 2016 resolution that recognized the historical significance of this final resting place for nearly 6,000 souls, more than 1,000 of whom had served in the military.

However, some felt a sense of betrayal by early 2017. Gray had registered a nonprofit corporation named Lincoln Cemetery Society, Inc., in June 2016. She also held quiet conversations with the property’s owner of record. On February 8, 2017, Gray’s nonprofit acquired a deed to Lincoln Cemetery that she recorded with the clerk of the court less than a week later.

When Gray’s nonprofit assumed control of the cemetery, this move surprised some and angered others. Some in the African-American community – including leaders from the Greater Mount Zion AME Church in St. Petersburg and the Pinellas County Urban League – had started to develop long-range management plans. They hoped to manage the cemetery and were caught off guard.

Some questioned the legitimacy of the transfer. Others wondered about the ability of Gray’s nonprofit to run an ailing cemetery that previous owners had run into the ground. These conversations sometimes touched upon the delicate issue of race.

Digging up the historical dirt

Lincoln Cemetery owes its existence to persistent patterns of racial segregation coupled with the pressures of the 1920s Florida land boom. As St. Petersburg’s municipal boundaries expanded during the height of the land boom, officials sought to contain the city’s Black community into a couple of segregated residential districts and remove their cemeteries to locations outside of the city limits.

Lincoln Cemetery owes its existence to persistent patterns of racial segregation coupled with the pressures of the 1920s Florida land boom. As St. Petersburg’s municipal boundaries expanded during the height of the land boom, officials sought to contain the city’s Black community into a couple of segregated residential districts and remove their cemeteries to locations outside of the city limits. Photo by Shelly Wilson

At that time, the three cemeteries with the majority of Black burials were Evergreen, Moffett and Oaklawn. They existed on lands west of 16th Street South, most of which are now parking lots for Tropicana Field. During the 1920s, much of the footprint of the Tropicana Field site east to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Street was an area known as the “Gas Plant” neighborhood, one of two enclaves where Blacks lived.

City officials issued condemnation orders for all three cemeteries in 1926, prohibited any additional burials, and called for the removal of bodies already buried at these locations. An upcoming article discusses these St. Petersburg cemeteries in greater detail.

Sumner Marble and Granite Works began to relocate some bodies from these locations to the newly established Lincoln Cemetery in 1926. When it first opened, Lincoln sat on a remote tract of land. Aside from the narrow and mostly dirt path that 58th Street was at that time, the only nearby landmarks were the Seaboard Air Line railroad tracks on its northern boundary (the present-day Fred Marquis Pinellas Trail) and rows of citrus trees east of 54th Street.

At this quiet and secluded location, Black residents from St. Petersburg could pay respects to the departed without fear of harassment. No homes or subdivisions appeared in the area until the 1940s. To its south, the future campus of Boca Ciega High School remained a flood-prone area covered with scrub and small palms until construction began there in 1952.

Conditions deteriorated during the 1950s. During its early years, the grounds remained well-maintained, but owners failed to collect sufficient funds to ensure its perpetual care. By October 1952, people complained about piles of trash, grass and weeds covering headstones, and some gravesites starting to cave into the ground.

Standing water in depressed gravesites led to swarms of mosquitoes. Rattlesnakes larger than six feet regularly roamed the grounds during daylight hours. A massive cleanup of the cemetery and the nearly 3,000 gravesites on it at the time occurred in 1953. This situation grew worse over the next decade. Debris and waist-high weeds cluttered the site by mid-1964.

Lincoln Cemetery subsisted, literally and figuratively, on the “other side of the tracks.” Royal Palm (now Royal Palm Cemetery South) flourished on lands north of the tracks. Boca Ciega High opened in 1953 to the south. For many years, the Southern Regional offices for Little League Baseball and its multiple playing fields at 658 58th St. S. offered a barrier to discourage mischievous Bogie students from wandering into the cemetery.

Weeds and signs of a place in need

During the past half-century, Lincoln Cemetery has faced many instances where high weeds, missing headstones, and exposed gravesites raised concerns. In August 1968, St. Petersburg’s former afternoon newspaper, The Evening Independent, published an article titled “Lincoln Cemetery: Rest in Rubbish” that described tall grass, damaged headstones, gaping holes in graves, strewn beer cans, and other evidence of trespassers.

Sumner Marble and Granite Works had wanted to get rid of Lincoln for years. With few open burial spaces and hardly any funds to maintain the cemetery, this tombstone-maker and some members of the African-American community thought their prayers were answered when Sarlie McKinnon III agreed to take control of Lincoln in late 2009.

Having family members buried there, McKinnon pledged to maintain and restore Lincoln through a newly established nonprofit. He received more than $100,000 in perpetual care trust funds, but conditions continued to decline. By 2012, McKinnon terminated the nonprofit and managerial responsibility remained unclear as the City of Gulfport stepped in to prevent the grounds from further deteriorating.

This brings us back to Gray. She received a quit-claim deed in February 2017 from a member of the Alford family that were the last owners of record for Sumner Marble after it ceased operations. This deed revoked any claims Sumner Marble’s heirs may have had, transmitting their interests to Gray.

What happened at Lincoln has occurred elsewhere in Pinellas. Some of these situations have also affected the burial sites of people who lived here long before Gulfport existed, long before any African Americans lived in Florida. We examine those disturbing patterns in our next installment of “A Grave Situation.”