During Jim Crow St. Petersburg, Mercy Hospital was the only hospital that would serve Black people. Opened in 1923, the 3500 sq. ft. facility had no doctors on staff, and a handful of nurses provided treatment primarily to patients with infectious diseases, earning the facility the name of “pest house.”

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg and the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, Inc. (AAHA)presented the enlightening documentary “A Visual History of Civil Rights & Social Change in Pinellas County,” which delves into such topics as the history of the first Black settlers, establishment of Black neighborhoods and businesses, segregation, integration and voting rights.

Narrated in part by Gwendolyn Reese, president of the AAHA, the documentary serves as an entry point for education understanding and further exploration. The stories of how our community came to be are vital because they continue to shape who we are today. Without knowledge of where we’ve been, it’s challenging to move forward in a way that prioritizes equity for all.

Segregated health care

Between 1903 and 1913, three hospitals opened in St. Petersburg, and none of them would care for African Americans. In July 1913, the Old Samaritan Hospital was moved to a new site to serve the Black community. There were no doctors on staff, and a handful of nurses provided treatment primarily to patients with communicable diseases, earning the facility the name of “pest house.”

Dr. James Maxie Ponder

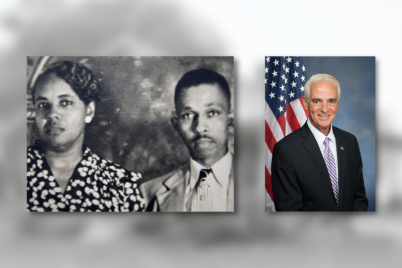

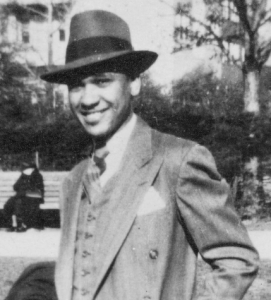

In 1923, the 3500 sq. ft. Mercy Hospital opened, and in 1926 Dr. James Maxie Ponder became the first Black staff physician. Dr. Ponder, his wife Fannye Ayer Ponder, and their son Ernest moved here from Ocala. Reese noted that he was the only Black staff physician for more than ten years.

In 1940, Dr. Breaux Martin moved to St. Pete, opened a medical office, and joined the staff at Mercy Hospital, becoming the hospital’s second staff physician. Two of his sons were born at Mercy. Tired of the restrictions of Jim Crow, Dr. Martin moved to Toledo, Ohio, in 1949.

Dr. Orion T. Ayer filled the void left by Dr. Martin’s departure, Reese said. He arrived with his wife Helen and his three children in 1949 and provided medical care for the community for more than 35 years.

Dr. Fred W. Alsup

Dr. Fred W. Alsup opened his private practice and joined the Mercy Hospital staff in 1950.

With his arrival, Mercy Hospital now had three doctors on staff. Dr. Alsup was also one of the pioneering civil rights activists in the community who fought against the segregated conditions in the hospital and the city at large.

Dr. Ponder retired as city physician to the Black community in 1951, and over the next few years, three more physicians joined the Mercy Hospital staff: Drs. Wimbish, Rose, and Taliferro.

Dr. Ralph Wimbish

In 1951, Dr. Ralph Wimbish established a practice in Tampa and built a home, which arsonists burned. He moved his family to St. Petersburg and joined the staff at Mercy Hospital and was named assistant city physician.

In 1953 Dr. Eugene Rose joined the Mercy staff. He cared for Dr. Alsup’s patients when he was recalled to the military from 1953 until 1955.

Dr. Harry F. Taliaferro was the last Black physician to join Mercy’s staff. He initially established his practice in Clearwater but later moved to St. Pete.

Other staff at Mercy Hospital included a cadre of trained nurses who assisted the physicians in providing essential and quality medical care and the Gray Ladies — volunteers who performed non-medical tasks, freeing nurses for other duties.

Healthcare workers at Mercy Hospital struggled to use discarded and outdated equipment, faced overcrowding, and had no pharmacy and no laboratory. For nearly 40 years, Mercy Hospital was the only hospital in the city that treated and cared for African Americans.

On Feb. 23, 1961, Reese said that a decision was made to integrate Mound Park Hospital in a private meeting. Two days later, Dr. Alsup admitted Altamese Chapman to Mound Park Hospital, now Bayfront Medical Center, effectively desegregating the whites-only hospital. In 1966, Mercy Hospital transferred the last of its patients and staff to Mound Park and, after 43 years, closed its doors.

Dr. Ponder, Mercy’s first Black physician, died on Mar. 4, 1958.

“It is said that he wrote the first prescription for Webb City’s drug store,” Reese said. “When Dr. Ponder died, the flag at city hall was flown at half-staff during his funeral, and a bronze plaque was placed in his memory in a new wing of Bayfront Medical Center.”

Lynching in St. Petersburg

From Reconstruction until the Civil Rights Movement, white people carried out lynchings to terrorize, punish and control Black people.

Between 1900 and 1930, Florida had the highest ratio of lynchings to minority populations of any state in the country, and Tampa had the most lynchings of any Florida city or county during the same period.

In 1905, John Thomas was lynched on Christmas Day. Thomas killed the St. Petersburg police chief while being arrested on a disorderly conduct charge, Reese said. A mob of white men stormed the jail, overpowered police officers, and shot and killed Thomas. No one was arrested or charged with his murder.

Both African Americans, John Evans and Ebenezer Tobin, were suspected of murdering white photographer Ed Sherman and attacking his wife, Mary Sherman. John Evans was lynched at Ninth Street, now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Street, and Second Avenue South on Nov. 12, 1914, by a mob of 1,500 white men, women, and children.

A year later, Tobin was put on trial for murdering Ed Sherman and attacking his wife. He was found guilty on Sept. 17, 1915, and sentenced to be hanged.

“It took the jury 15 minutes to determine his guilt,” Reese said.

He was hanged at 11:06 a.m. on Oct. 22, 1915, and his execution was Pinellas County’s first legal hanging. He was buried in a pauper’s grave.

Parker Watson was lynched on May 9, 1926, at the hands of a group of masked, armed men as three police officers were taking him to the county jail. His body was found along an isolated road the next morning — he had been shot five times and had acid, or other chemicals poured on his face.

On Feb. 23, 2021, the Community Remembrance Project Coalition and the Equal Justice Initiative unveiled the John Evans Lynching Memorial on Second Avenue and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Street. Evans was brutally lynched and shot on Nov. 12, 1914. Photo courtesy of the City of St. Pete.

Unlike the lynching of Evans in 1914 — when public officials and upstanding citizens were members of the lynch mob and were said to have planned it the night before — the Watson lynching brought outcries from a number of people, including St. Petersburg ministers. During a special session, the county commission condemned the lynching in a resolution and offered a reward of $1,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the guilty parties. The perpetrators were never identified or prosecuted.

These documented lynchings are likely not the only ones that occurred. The death of so many Black people today at the hands of law enforcement and self-styled vigilantes reminds us that the fight for equal rights and the equal value of Black lives is far from over.

‘Some’ women get the vote

In 1920, the Florida legislature failed to support the 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote, but enough states did so to make it law. Mary May Jennings, married to Florida’s governor in 1900, used her position as first lady to campaign for women’s rights to vote and founded Florida’s League of Women Voters.

Founding members of Delta Sigma Theta marched in the first suffrage parade in 1913.

Such Black leaders supported the suffrage movement as Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Mary Church Terrell and Frederick Douglass, Reese said. Yet, with the passage of the 15th Amendment, white suffragists began to push for voting rights for white women only, excluding all women of color.

Many of these suffragists worked alongside and even accepted funding from white supremacists. When the first suffrage parade was held in 1913, planners initially decided to segregate the march. They later agreed to allow Black suffragists to march in the rear.

“Ida B. Wells-Barnett, leader of the anti-lynching crusade, ignored the instructions, stepped off the sidewalk, and marched with the Illinois delegation,” Reese said, noting that 22 founding members of the Black sorority Delta Sigma Theta also marched in the parade that day.

In 1920, the 19th Amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote was passed, but it didn’t guarantee that right for all women. It would be 45 more years before Black women could vote — not until the passing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Strategic disenfranchisement of Black and Brown people remains a popular political tactic. It has been more difficult to combat since the 2018 Supreme Court ruling reversed federal oversight of state election practices. This opened the door to aggressive purges of voter rolls and other voter suppression tactics that disproportionately impact communities of color.

Next in this four-part series, we’ll explore integrating public spaces and combatting racist representation.