Like many other public spaces, Black people were not allowed to sit on St. Pete’s famous green benches.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg and the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, Inc. (AAHA) presented the enlightening documentary “A Visual History of Civil Rights & Social Change in Pinellas County,” which delves into such topics as the history of the first Black settlers, establishment of Black neighborhoods and businesses, segregation, integration and voting rights.

Narrated in part by Gwendolyn Reese, president of the AAHA, the documentary serves as an entry point for education understanding and further exploration. The stories of how our community came to be are vital because they continue to shape who we are today. Without knowledge of where we’ve been, it’s challenging to move forward in a way that prioritizes equity for all.

Integrating public spaces

St. Petersburg’s Central Avenue was famous for its green benches, as they were a symbol of relaxation and spoke a message of welcome for the city. But like many other public spaces, the message to African Americans was much different.

Although the labor of African Americans was significant to the growth of St. Petersburg, their presence was not wanted, Reese said. As the Black population grew, so did the enforcement of Jim Crow laws.

“Racial and social segregation was strictly enforced, and at one time, St. Petersburg was one of the most residentially segregated cities in the country,” Reese said. “The benches were only for the enjoyment of white people. The benches were off limits to African Americans, as were most of the recreational amenities, lunch counters, theaters, and in many instances, the public restrooms in places of business.”

In 1954, Dr. Robert Swain, Jr., a dentist, civil rights activist, civic leader, and owner of the Robert James Hotel in Methodist Town and other properties in the city, challenged the redline policy which prevented African Americans from living or operating businesses on the south side of 15th Avenue.

Swain crossed the line and opened a dental office and a small apartment building initially intended to house Black baseball players on the southwest corner of 22nd Street and 15th Avenue South. The city initially refused to issue building permits but backed down when Swain threatened to sue.

On Nov. 30, 1955, the day before Rosa Parks effectively launched the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Black leaders in St. Petersburg sued to integrate downtown Spa Beach and pool. The episode ignited more than a decade of spirited desegregation efforts, which included the picketing of segregated movie theaters, a strike by Black sanitation workers, and a suit against the city by Black police officers for equal treatment.

Ralph M. Wimbish, physician, civic leader and civil rights activist, served as president of the St. Petersburg chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) during a time of strife, turmoil, and relentlessness in challenging the city’s segregation laws.

During the struggle for civil rights, Rev. Enoch Douglas Davis worked to end busing, school segregation, and employee discrimination to win voting rights for Blacks and to open the city’s beaches and public pools to the Black community, Reese said.

Rev. Enoch Douglas Davis worked to end busing, school segregation and employee discrimination to win voting rights for Blacks and to open the city’s beaches and public pools to the Black community.

“He also led his share of sit-ins at lunch counters and theaters. When the Freedom Riders came to Florida in the late 1950s to protest interstate segregation laws, Rev. Davis allowed them to stay in his home and to use the church as headquarters,” Reese said. “With the help of his brother, the police and several neighbors, he offered them protection from agitated segregationists. He earned several threats on his life for this and other civil rights work.”

When Black garbage workers marched during a 116-day strike against the city in 1968, Davis marched with them. His work in civil rights earned him 11 honors. Today, the Enoch Davis Center — a multi-purpose community center with a library and science center, a 250-seat auditorium and offices — bears his name.

In St Augustine, in 1964, Black people tried to integrate a whites-only hotel by swimming in its pool. A dramatic news photo of the hotel owner dumping acid in the water horrified the nation and encouraged President Lyndon Johnson to sign the Civil Rights Act the next day. Even when laws changed, de facto segregation, discrimination, harassment and threatening behavior continued as common practice.

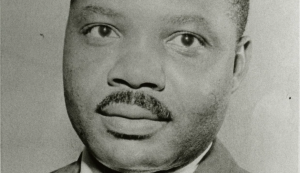

In 1965, Black police officers were only allowed to patrol predominantly Black neighborhoods and had no authority to arrest white citizens. The Courageous 12 were 12 of St. Petersburg’s 15 Black police officers who sued the city for the right to patrol white communities and arrest white people, the same as their white counterparts.

They were Adam Baker, Freddie Crawford, Raymond DeLoach, Charles Holland, Leon Jackson, Jr., Robert Keys, Primus Killen, James King, Johnnie B. Lewis, Horace Nero, Jerry Styles and Nathaniel Wooten.

On May 11, 1965, a year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law, the group led by Freddie Crawford and represented by Attorney James Sanderlin filed a lawsuit against the city in federal court. On Aug. 1, 1968, the officers won their case. Their courageous act opened the door for Black police officers in this city and throughout the nation.

As of today, Leon Jackson, Jr., the first Black officer assigned to an all-white neighborhood, is the last surviving member of the Courageous 12. A plaque in the group’s honor hangs in the St. Petersburg police headquarters, and soon a monument dedicated to them will be included in the makeover of the old headquarters.

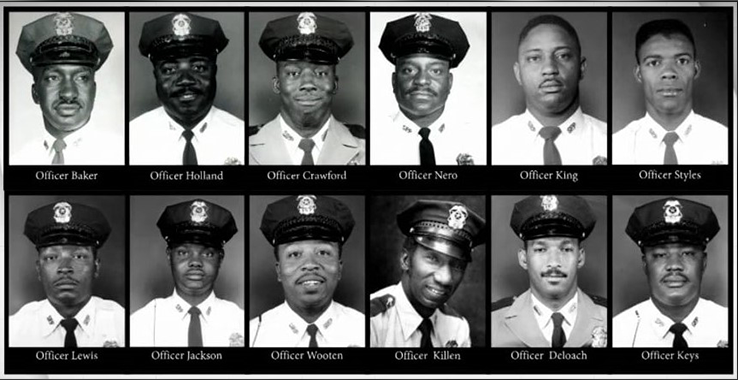

Joseph E. Savage, a sanitation worker, spearheaded a movement leading 211 to 300 of his fellow workers to walk off their jobs in May 1968.

Joseph E. Savage, a sanitation worker, spearheaded a movement leading 211 to 300 of his fellow workers to walk off their jobs in May 1968. This was just over a month after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968, in Memphis.

Dr. King was in Memphis to support and bring attention to a strike by more than 1,300 of the city’s sanitation workers. Dr. King’s brother Rev. A.D. King came to St. Petersburg to support the workers here, as did Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy. The strike for better pay and working conditions lasted 116 days, during which racial tensions exploded in various ways.

The strike is seen as a milestone in local civil rights history. The following year C. Bette Wimbish, the first Black council member, was elected, and a few years later, James B. Sanderlin, the young lawyer who represented the striking workers, would be elected the first Black judge in Pinellas County.

Combatting racist representation

In December 1966, activist Joe Waller, later known as Omali Yeshitela, ripped a mural down from the walls of city hall. He was arrested, and his trial and appeals lasted five years, with his attorneys arguing all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

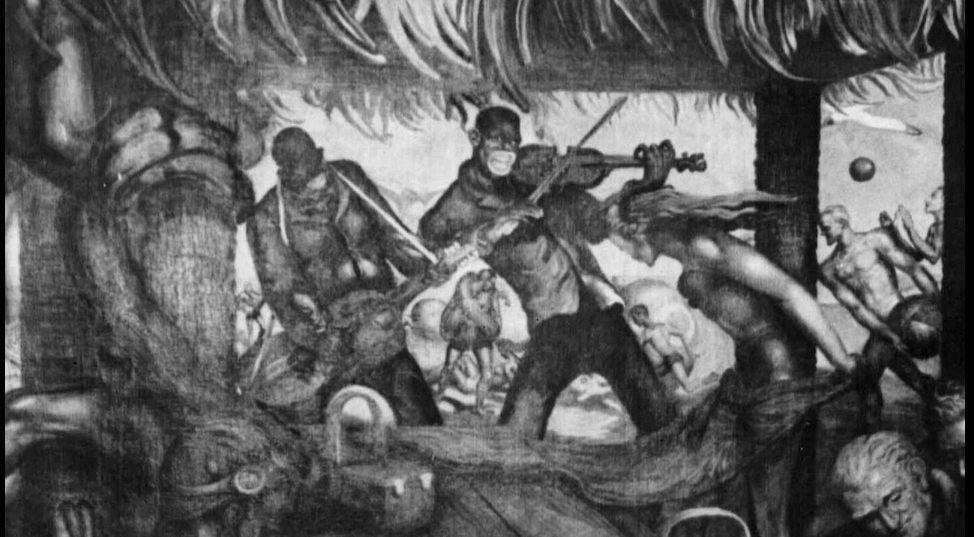

“The mural depicted a group of Black troubadours, musicians, entertaining white picnickers at Passe-a-Grille Beach, “Reese explained. “The mural was a caricature of Black people, depicting them with oversized heads and huge pink lips, grinning while strumming banjos. The mural was seen as racially offensive and denigrating by many in the Black community.”

The racist mural that hung in City Hall depicted a group of Black troubadours, (musicians) entertaining white picnickers at Passe-a-Grille Beach.

Waller served at least 22 months in prison and was ineligible to vote until his rights were restored in 2000. Many regard his action as the spark that reignited the civil rights movement in St. Petersburg. A plaque commemorating this action will be installed on the wall in city hall where the mural once hung.

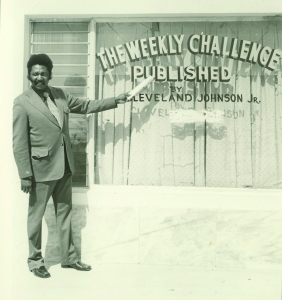

There is a history of misrepresentation, omission, and disrespect of Black citizens in the mainstream white media across the country. Black-owned newspapers were created to give the community their own voice. In St. Petersburg, The Weekly Challenger newspaper has documented the vibrant history of the African-American community for more than 50 years.

In 1967, Cleveland Johnson, Jr., founder and publisher of the paper, bought what would become The Weekly Challenger from M.C. Fountain. Johnson expanded the paper from a few pages to 32, including eight pages in color, and rebranded the paper to one with the primary focus of highlighting African-American news, both locally and nationally.

The paper informed the Black community of events related to the Civil Rights Movement, school desegregation, local events, church news, entertainment news and news of the life and death of members of the local community.

The legacy of The Weekly Challenger newspaper lives on, and it holds the place of respect and honor in the hearts of many in the African-American community.

In the last installment of this four-part series, we’ll explore LGBTQ+ rights, school resegregation and disability rights.