Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s 1944 release “Down by the Riverside” was selected for the National Recording Registry of the U.S. Library of Congress in 2004.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

From blues to boogie-woogie, from jazz to soul, from R&B to rap, there is no question that African Americans have left their stamp in almost every musical genre (if they didn’t outright invent it!), and this includes rock and roll.

These are a few of the many historical moments in which Black musicians played a crucial role in the world of rock and American pop culture.

The grande dame of rock plugs in

As someone who had mastered the guitar by age six, Sister Rosetta Tharpe once claimed: “No man can play like me. I play better than a man.” As her string of influential songs from a long, fruitful career would prove, this was no empty braggadocio by one of the first women to play electric guitar.

Considered a child prodigy in Cotton Plant, Ark., Tharpe would sing and play guitar alongside her mother, Katie Bell Nubin, in gospel concerts all around the South and joined her mother in performing at church conventions as part of an evangelical troupe by 1921.

Later after a move to Chicago and then to New York, Tharpe’s talent earned her a stint with Lucky Millander’s Orchestra and a spot at the famed Cotton Club. With the orchestra, Tharpe played gospel and secular songs, and in 1938, at 23, she recorded her first sides, including “That’s All” and “Rock Me,” which would become her first hit.

Her unique blend of spiritual lyrics, fluid guitar licks and rhythmic accompaniment made her a one-of-a-kind innovator of pop gospel and a precursor to the rock and roll sound. Infusing energy and elan into her songs — her powerful mezzo-soprano voice didn’t hurt, either — she was also among the pioneers in using distortion on her electric guitar, laying the groundwork for electric blues and, ultimately, rock.

In time, many would point to Tharpe, who would be labeled the “Godmother of Rock and Roll,” as a resounding influence. Listen to her song “This Train,” and you can hear Little Walter’s 1955 number-one R&B hit “My Babe.” Listen to the opening of “The Lord Followed Me,” and you can hear pretty much every riff Chuck Berry ever played, all at once. Tharpe helped shape the sound of the next generation, which included upstarts like Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins, and she did it her own way — that is, playing like a girl.

In a long overdue honor, Tharpe was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2018.

Billy Ward and his Dominoes clock in

Boasts of prowess (and stamina) in the bedroom are nothing new in the world of rock and roll, but when Billy Ward and his Dominoes put out their single “Sixty Minute Man,” they may have beaten everyone to the punch, so to speak.

Billy Ward and his Dominoes was formed by Ward while he was a vocal coach and part-time arranger in New York in the early 1950s.

The group, formed by Ward while he was a vocal coach and part-time arranger in New York in the early 1950s, included silky-voiced tenor Clyde McPhatter, who would go on to stardom of his own. But it was the deep-voiced Bill Brown that seductively sang the lead on this 1951 single.

Over tasty, teasing guitar licks and McPhatter’s soulful backing vocals, Brown brags to the ladies that he’ll “rock ’em, roll ’em all night long,” and with his smooth and cocksure delivery, there is zero mystery as to what he means with the euphemism.

Lovin’ Dan — the narrator’s name in this tune — goes on to break down his agenda di amore, which includes 15 minutes of “kissin,'” 15 minutes of “teasin'” and 15 minutes of “squeezin.'” The crowning moment comes when Brown sings that he will spend the final 15 minutes “blowin’ my top,” a single-entendre if there ever were one.

With his machismo at stratospheric levels, Lovin’ Dan croons that if the ladies don’t believe him, they should take his hand, and when he finally lets them go, they’ll cry: “Oh, yes! He’s a sixty-minute man!”

The raunchy single broke into the R&B charts and shot to the top, remaining for 14 weeks. And then it did something R&B tunes of those days rarely did — it crossed over to the coveted pop charts, where it reached #17. “Sixty Minute Man” was an innovative blending of gospel and R&B. Yet, the bouncy tune emphasized the second and fourth beats, so it can lay a reasonable claim the title of the first rock and roll song — if nothing else, it was one of the first songs to even mention the term “rock and roll.” But more importantly, it brazenly pushed (boy, did it ever!) the limits of what was acceptable in 1950s strait-laced America and ultimately appealed to Black and white audiences alike.

The group recorded a tongue-in-cheek follow-up in 1955 with a tired-out version of “Old Dan” lamenting his “blown-out fuse” in the lyrics, titled “Can’t Do Sixty No More.”

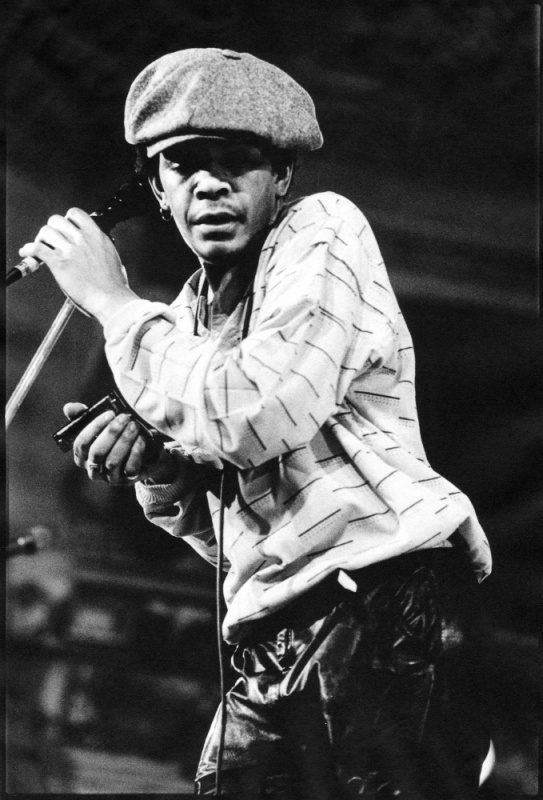

Sugar Blue goes busking underground, comes up big

Sugar Blue (James Whiting) is probably best known for playing with the Rolling Stones.

Talk about being in the right place at the right time.

A gifted harmonica player from Harlem, James Whiting began his career as a street musician and session man in the mid-1970s before deciding to take his talents abroad to Europe. One day while performing in the Metro subway in Paris, Whiting — who had adopted the more colorful stage name Sugar Blue — caught one doozie of a break.

The story goes that someone who was close to a certain rock band heard Whiting’s wizardry with his blues harp and was so impressed that he decided there could be a place for the young virtuoso on the group’s upcoming album.

The band turned out to be none other than the Rolling Stones, and the album was their 1978 effort “Some Girls,” which they were recording in the City of Light at the time. It was on the record’s disco-flavored lead-off song “Miss You,” about a lovesick man “shuffling through the streets” and longing for his woman that Sugar Blue made his mark.

Bending, molding, and massaging the mournful notes from his harmonica, he unleashed the perfect bluesy blend of wistfulness and desire to match the sultry yet yearning vocals of Mick Jagger. Wandering Central Park, singing after dark? Seeping all alone, hanging on the phone? The sweet notes that pour from Sugar Blue’s harp say it all with doleful eloquence.

Making the most out of being admitted into the Stones’ inner circle, Sugar Blue not only appeared on a couple of the group’s subsequent albums but performed with them on multiple occasions. He has also played alongside other heavyweights such as blues legend Willie Dixon, folk-rock icon Bob Dylan and the unclassifiable Frank Zappa. He has released his own albums featuring his modern blues style.

But he’ll probably always be best remembered for infusing his soulful touch into a song that would become a number-one hit by one of the world’s greatest rock groups.

Not a bad break for a kid showing off his chops in the subway.

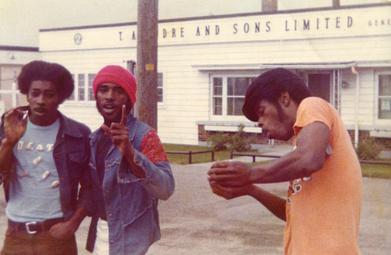

Death punks out

The Detroit band Death, comprised of brothers Bobby, David and Dannis Hackney, began life as a funk group in the early 1970s called Rock Fire Funk Express. After attending concerts by hard rocking acts like the Who and Alice Cooper, they decided to turn up the volume and switch to rock, which set them apart from other all-Black groups at the time. In 1974 they changed their name to Death as an homage to their father after he had died in an accident.

The heavy, angry chords of David’s guitar, the relentless assault of Dannis’s drums, and the urgency of Bobby’s rapid-fire vocals made Death arguably the first punk band, period. This is most evident in their song “Politicians In My Eyes,” with its intense, angry fusion of funk, rap, and rock.

The song is supercharged with angst and lays down some solid groundwork for future punk rockers to emulate. “It’s like a race to the top because they want to be boss | They don’t care who they step on as long as they get along,” Bobby sings in his take-no-prisoners attack on politicians and their indifference when they “hear the people cry.”

The Hackney brothers recorded seven songs at Detroit’s United Sound Studios in 1975. hey were going to record a dozen, but according to the band, Clive Davis, who funded the sessions, ultimately retracted his support when Death refused to change the band’s name to something more palatable.

The following year they released “Politicians In My Eyes” on their label Tryangle Records, but only 500 units were issued. The band dissolved in 1977 — by then, punk rock had exploded on both sides of the Atlantic — with relatively few people having even heard of this visionary band, much less experienced their trailblazing music.

A couple of Death songs surfaced online in the 2000s. It wasn’t until 2009 that Drag City Records finally released the United Sound sessions on vinyl and CD under the title “…For the Whole World to See,” featuring such blistering tracks as “Keep On Knocking,” “Rock-N-Roll Victim,” Freakin Out” and “Where Do We Go From Here???”

Following this release, Bobby’s sons Julian, Urian and Bobby, Jr. formed Rough Francis, a band that covered the songs of Death and introduced their father’s band to a new generation of punk rock lovers.

Living Colour kicks off a ‘Cult’

Hard rock and heavy metal had long been the domain of primarily white acts since hard rock and heavy metal began. But in 1988, an African-American band from New York City helped blow up that notion with their explosive debut album “Vivid.”

Living Colour was formed in New York City in 1984.

Guitarist Vernon Reid formed Living Colour in 1984 with a revolving door of members. Yet, it wasn’t until the permanent lineup of Reid, vocalist Corey Glover, bassist Muzz Skillings and drummer Will Calhoun fell into place that the band really gelled and burst onto the scene with “Vivid.”

The album includes a collection of fresh-sounding tracks that include everything from straight-up rock to funk metal to hardcore (there’s even a revved-up reworking of the Talking Heads’ song “Memories Can’t Wait”) was lauded by critics as one of the best hard rock records of the 1980s.

The album’s devastating opening punch, “Cult of Personality,” featured one of the most recognizable riffs by anybody, ever. Reid’s buzz saw guitar comes tearing in and maintains an insanely relentless pace, pursued all over the place by booming drums and a thumping bass.

Glover sings not only about the huge followings political figures can attract, good or evil — Mussolini and Kennedy are mentioned in the same line while Stalin and Gandhi are paired together in another — but anything in our culture that can sway our minds and psyches: “I sell the things you need to be | I’m the smiling face on your TV | Oh, I’m the cult of personality.”

This turbo-charged single rose to #13 on the Billboard Hot 100, #9 on the Billboard Alum Rock Tracks chart and won the Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock Performance. The song’s video scored the MTV Music Video Award for Best Group Video and MTV Music Video Award for Best New Artist, showing that an all-Black group could rock with the best head-banging bands.