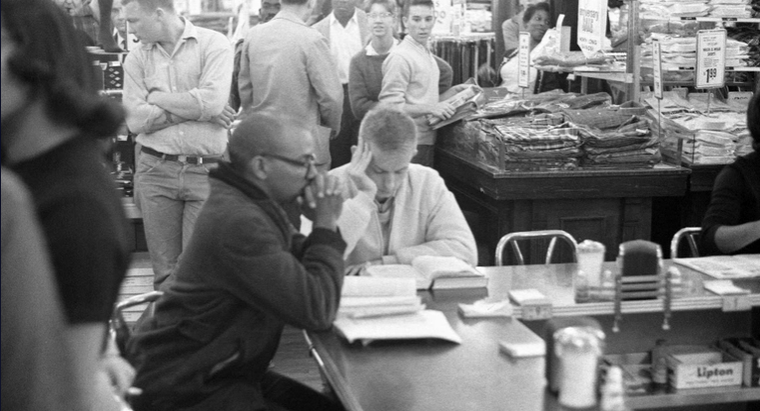

Filmmaker Valerie Scoon discussed her award-winning documentary at ASALH’s Black History Month Program with Judge Charles Williams.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) held its seventh annual Black History Month celebration at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg campus. This year’s keynote speaker came with a documentary in tow.

Writer, director, and producer Valerie Scoon, who was an executive at Oprah Winfrey’s Harpo Films, has a long list of credits under her belt, such as the Golden Globe-nominated “The Great Debaters” starring Denzel Washington, “Beloved” by the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, Toni Morrison, made for TV movies, “Their Eyes Were Watching God” and “The Wedding” both starring Halle Berry.

Scoon’s latest job title of Florida State University College of Motion Picture Arts filmmaker-in-residence, where she wrote and directed the award-winning documentary “Invisible History: Middle Florida’s Hidden Roots,” is what brought her to USF on Feb. 25.

She and her small family moved to Tallahassee from California and noticed a graveyard for the enslaved down the street from their home.

“So, I started looking up about the plantations, and that’s when I came to realize that all of Tallahassee and the general surrounding areas were nothing but plantations, and I thought, why don’t I know this,” she asked herself. “And I thought, I don’t know this because there are no markers. There’s nothing that says that this was here.

She was inspired to go on a journey of understanding to understand Tallahassee better and honor the 9,000 or more enslaved people who lived and died there and, for the most part, almost forgotten.

“And so that’s a journey I took, and I decided since I’m a filmmaker to make it a film,” Scoon explained.

‘Invisible History: Middle Florida’s Hidden Roots’

In the nearly one-hour documentary, Patrick L. Mason, director of African Studies at FSU, explained that plantations were part of a system of international trade and a whole series of other industries developed around it.

“People coming from Western Africa, people coming from Western Europe, agricultural products going back there, finished products coming back here,” he said. “And around this whole process of slavery you get shipping, you get banking, you get international insurance.”

Larry E. Rivers, Ph.D., distinguished professor, History and Political Science at Florida A&M University, said that 45 percent of enslaved people produced 90 percent of all the cotton in Florida by 1860.

“Cotton, which made Florida the most money, would not have been the product of choice had it not been for the labor of enslaved persons,” he said. “They were indispensable to increasing Florida’s economy.”

European explorers conquered or expelled the indigenous people in the center of Florida’s Panhandle, once known as Middle Florida, and claimed the fertile land as their own. In the 1800s, wealthy planters from the upper South with family ties and political connections joined the battle to conquer the indigenous populations to dominate this new territory.

Jonathan Grandage, executive director of the Grove Museum, noted that their whole purpose for coming here was to remove the indigenous people by force and change the uses of the land into extensive cotton cultivation.

“The land becomes the property of the federal government,” he said. “Florida is a United States territory, and so the land was surveyed and put up for sale.”

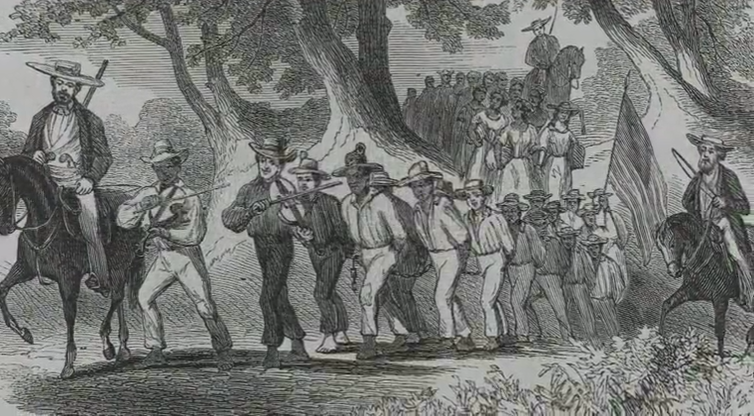

From 1820 to 1860, a second mass migration of enslaved people were forcibly marched from the upper to the lower South.

From 1820 to 1860, you had what we call the second mass migration of enslaved people, Rivers explained. The first mass migration was moved from Africa to the Americas, particularly to the colonies, but the second mass migration was from the upper to lower South. During a forced march of a disproportionate number of men from Virginia to a plantation in Jefferson County in Florida, many husbands, wives, and children were permanently and tragically separated. Whites rode in wagons while the enslaved walked.

Mason said that many people came to Florida thinking that Tallahassee would be the new Richmond, Va. They found a hostile environment instead, complete with yellow fever, mosquitoes, wild animals and even a violent environment where duels were rampant. Over time, plantations developed, which allowed the white owners to accumulate a great deal of wealth. By 1860, Leon County and the immediate surrounding counties would make up the “cotton belt of Florida,” and the enslaved population would make up nearly 70 percent of Leon County.

Bill Walter, docent and board member of Goodwood Museum and Gardens, said one of the “languages of power” for sprawling plantations was the enslaved people. By 1850, the Goodwood plantation would have nearly 200 enslaved men, women, and children.

“The real wealth was in enslaved people,” Rivers said. “They had a term for enslaved people: ‘walking cash.'”

Maxine Jones, Ph.D., said that women generally sold less than men, and in some places, babies might be sold by the pound. To finance his plantation operation, owner Hardy Croom sold his enslaved, and during an 1832 trip to Louisiana, he sold five women and three men for $4,000. He also sold a 10-year-old boy for $350.

Slave labor contributed to the building of not only plantations throughout Middle Florida but ports, railroads and the capitol. Jones pointed out that we haven’t often acknowledged that the money that was used to build what became Florida State University “probably came from the labor of Black bodies and the buying and selling of Black bodies.”

Running away from an enslaver was difficult for an enslaved person, especially in Florida, with its swamps and various hazards. Most of the enslaved who attempted to run away were young men committed to dying if necessary. Life in Florida was not easy for free Blacks, and if a free Black wanted to go to nearby Georgia, it would cost him $200, which many did not have.

“It became harder to free enslaved persons after 1830,” Rivers said. “There was a push to limit the number of free Blacks throughout Florida because they thought that they could be instigators, encouraging enslaved person to either fight or run away.”

John Finlayson, a descendant of an enslaver, remarked on an educated enslaved person his great-grandfather had bought, noting it was against the law to teach an enslaved person to read and write. Finlayson has a settlement of his great-grandfather’s estate, complete with a list of the human chattel.

“It was the most distressing thing,” he said, “to look at that settlement of his estate. The names of the enslaved came down, and then the names of the mules started. And they had to make a mark to show the difference where it was people and mules.”

Though the Emancipation Proclamation ostensibly brought freedom to the enslaved, many things stayed the same.

Many formerly enslaved Blacks turned to sharecropping to make a living and support families, giving the landowner somewhere between one-half and two-thirds of the crop — making it almost impossible to get out of debt.

“After Blacks were set free with no money or anything,” Rivers said, “the government initially talked about 40 acres and a mule. But the government decided, based upon all the pressure from the former Confederates, that this was not a good idea. They could not have a steady workforce if Blacks had owned their own land, so there was an effort after slavery to systematically make sure that Blacks would not become economically independent.”

Many formerly enslaved Blacks turned to sharecropping to make a living and support families, giving the landowner somewhere between one-half and two-thirds of the crop — making it almost impossible to get out of debt. In a sense, it was a form of “generational poverty,” as the farmers had to pledge not only their labor but the labor of their wives and children for the next season’s crops.

During the Reconstruction period, from 1865-1877, there was hope in Florida for the Black populace as the Secretary of State and the Superintendent of Education were Black men. People were registering to vote, and many formerly enslaved persons attended schools. Church schools, Mason said, doubled as places where people learn to read and write.

“The church becomes this place that it’s not just religious worship,” he said. “It’s a community center, and it’s also where a lot of the informal leadership is.”

James Page, a formerly enslaved man, would emerge as a preacher who supported education and enfranchisement in every way. The church he founded, Bethel Missionary Baptist Church, remains active over a century and a half later. John Gilmore Riley, a formerly enslaved person from Leon County, became secretary of the NAACP and the first African-American principal at the first school for Blacks to provide secondary education.

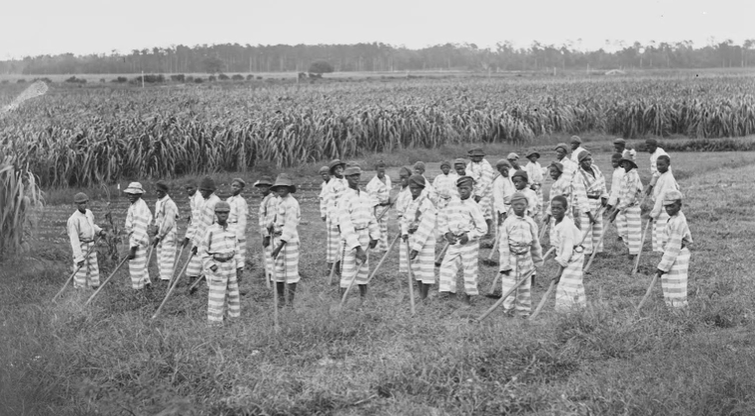

Following Reconstruction, slavery persisted in the form of convict leasing, a system in which Southern states leased prisoners to private railways, mines and large plantations.

With the advent of Jim Crow laws following Reconstruction, many Blacks were arrested on trumped-up charges, Mason explained and were leased out to work. Because they now had a criminal record, they couldn’t vote. In Leon County, the Black population outnumbered the white population six to one.

“So, what will you do when you’re outnumbered, and people will outvote you,” Mason asked. “You have to find a way of suppressing the vote. That does not change from 1865 to 2020.”

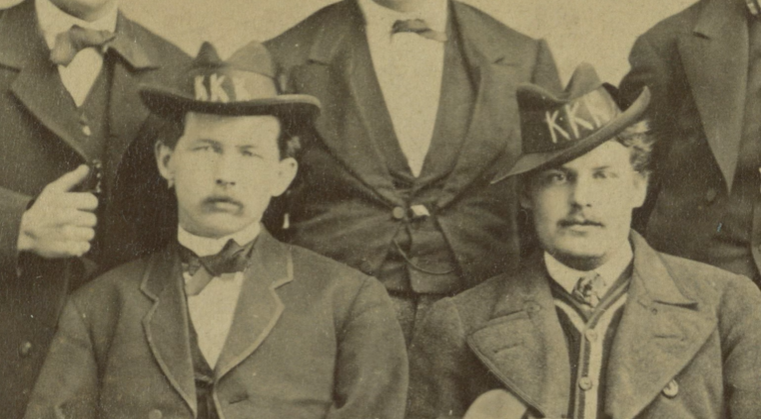

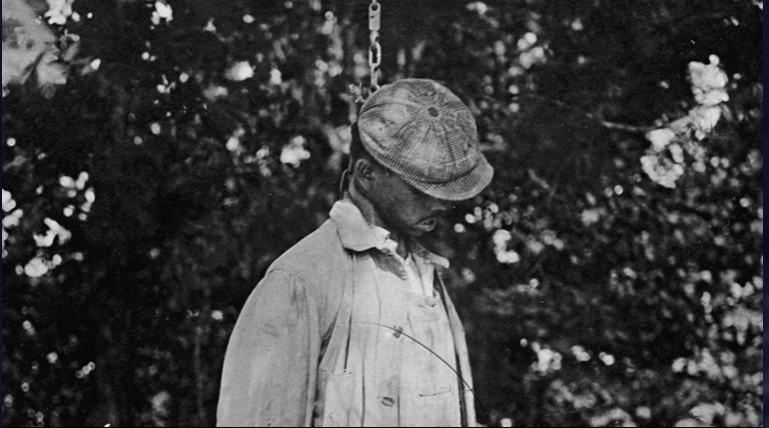

As determined by the state legislature, a felony conviction in those days meant a loss of voting rights for life. The Ku Klux Klan also emerged to intimidate and terrorize newly freed Black people. Well into the 20th century, Black people were expected to defer to whites if they came in contact with them or suffered dire consequences that could include burnings and lynchings. Though the number is almost certainly higher, four documented lynchings occurred in Tallahassee from 1897-1937.

The Ku Klux Klan emerged during Reconstruction to intimidate and terrorize newly freed Black people.

“It’s the fear that is used to control Blacks,” Jones said.

Althamese Barnes, executive director at the John Gilmore Center, recalled the tragic story of a young man, one of the Beard family, with whom she attended school.

“I heard them talking about Abraham Beard would be electrocuted next week, or whatever it was,” she remembered. “In my mind, it just seems like that was such a dark day, like an overcast day. It ended up that the lady confessed. She did not tell the truth, that he did not assault her—but it’s too late.”

Though the number is almost certainly higher, four documented lynchings occurred in Tallahassee from 1897-1937.

University students from schools like FSU and FAMU partly sparked the state’s Civil Rights Movement. Others in the community would join in, and many churches — Bethel Missionary Baptist Church among them — as meeting places. Rev. C.K. Steele, the pastor of Bethel, supported the bus boycott that would result in the desegregation of buses in Tallahassee.

While advances were made toward civil rights, many of the economic legacies of slavery would persist.

“You had policies in place that were systematically racist,” Mason said. “The effect of that is you get this huge racial difference in wealth during slavery. It’s locked into place and increased during Jim Crow so that by the time you get to the end of Jim Crow, say somewhere between 1965 and 1970, the amount of difference in wealth is so vast that you will have this racial problem locked in place for a very long time—unless you specifically deal with the wealth issue.”

University students from schools like FSU and FAMU partly sparked the state’s Civil Rights Movement.

Na’im Akbar, Ph.D.., clinical psychologist and retired professor at FSU, said that trauma so alters the human psychology that it could actually be transmitted from one generation to the next, and people continue to do things to try to defend themselves against reexperiencing the severity of trauma.

“For Black people, the depths of the hurt that occurred in slavery are so great that it really becomes a frightening thing to even approach it. So, for many generations, Black people didn’t talk about slavery. Today, even, it becomes a very difficult conversation to conjure among people who could really remember.”

Akbar added: “White people will have to confront the pain and the difficulty of the past that they want to deny. Black people will have to look at the hurt and the consequences of what we’ve done to deal with the hurt and put that in the context, as well, of seeing of what we did in spite of the hurt.”

Rev. C.K. Steele, the pastor of Bethel Missionary Baptist Church in Tallahassee, supported the bus boycott that would result in the desegregation of buses in Tallahassee.

The documentary closes by noting that today in Leon County and the surrounding area, there is little physical evidence or information regarding this painful shared past of enslavement. While the names of the plantation owners are present throughout the city as street signs and neighborhood names, historically, there has been little to no mention of the 9,000 enslaved who lived and died here.

However, in the last few years, the film noted, there have been efforts made to include the story of the enslaved at the few remaining plantations, and the recent designation of Emancipation Day as a paid holiday in Leon County is a positive step.

Scoon answered questions from the audience after the film.

Left, Judge Charles Williams, Dr. Raymond Arsenault, Filmmaker Valerie Scoon, ASALH President Jacqueline Hubbard, ASALH 1st Vice President Danny White

All historical photos used in this article were taken from the documentary Invisible History: Middle Florida’s Hidden Roots.