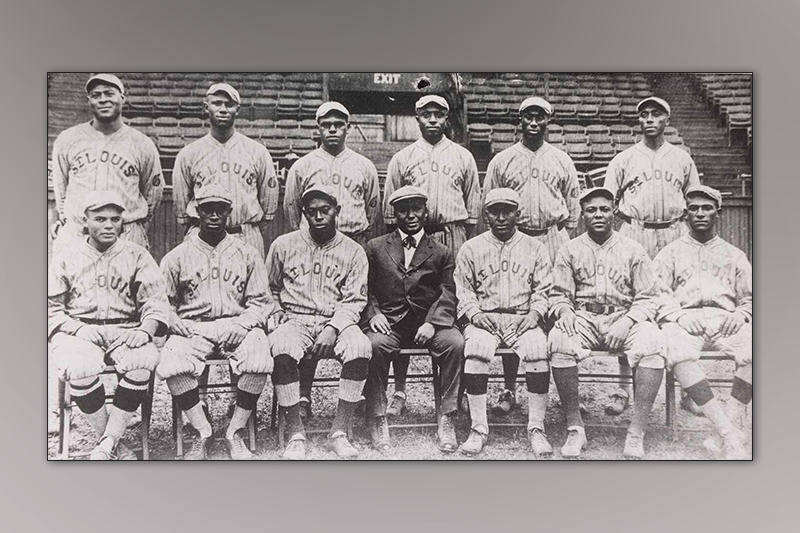

Photo of the 1916 St. Louis Giants with Ted Kimbro standing on the back row, third person in.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

Baseball, more than any other sport, truly serves as a harbinger of the season. For fans, it doesn’t really feel like springtime unless we can hear the whap of a ball hitting a glove, watch the perfect stroke of a swinging bat or even smell the freshly cut grass of a ballpark.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, baseball (along with other sports) has been forced to sit on the bench, patiently waiting for its time to take the field. But just over a century ago, another viral malady gripped the planet, affecting the sporting world as well.

From the backyards to the Negro Leagues, from sandlots to the Major Leagues, the destructive disease made its grim presence felt. Playing fields were no exception, as at least seven players in organized baseball succumbed to the 1918 influenza epidemic.

Ted Kimbro, born in St. Louis in 1895, was an up-and-coming star infielder in the Negro Leagues. He kicked off his pro career with the West Baden Sprudels in Indiana, where the 18-year-old shortstop got his feet wet appearing in only a handful of games, batting a meager .176.

The following year, he played in more than 30 games for West Braden, the Louisville White Sox and the St. Louis Giants. Starting to get a better feel for his opponents’ pitching, Kimbro managed to raise his average to .239.

Kimbro’s prowess as an infielder improved as he could flash the leather at shortstop, second base or third base. Soon he became more confident taking his swings as the youngster hit a solid .276 with St. Louis in 1916 before exploding to hit .350 in 1917 for the New York Lincoln Giants. Rapidly showing promise, his stock as a star was on the rise.

At the time, however, baseball was secondary for many Americans as the country was embroiled in a war with Germany. Many ballplayers left for military training camps before making the trip overseas to fight at the front lines in France. Kimbro did the patriotic thing by registering for the draft in June 1917, but claimed an exemption due to a rupture.

The next year Kimbro played for the Philadelphia Hilldale Club, Grand Central Red Caps and the Lincoln Giants. His exemption claim notwithstanding, he entered military service on July 18, joined by his teammate catcher Pearl “Specks” Webster, a talented player and accomplished hitter. Both were stationed at Fort Dix in New Jersey, played on the baseball team at the base, and even putting in some playing time with Hilldale and Lincoln Giants.

The horrific war would wind down to its inevitable end in a matter of months, but a marauding new adversary had begun to cast its shadow over the world. A gruesome influenza epidemic had raged in Europe and finally stormed our shores. This disease that ruthlessly attacked the respiratory system was first discovered stateside in Kansas in January 1918 — it would ultimately kill over ten times the Americans than all the battlefield’s bayonets and mortar shells combined.

By the summer, some professional ballplayers took their positions on the field and turn at-bat wearing face-covering masks. Ballgames were even banned in Baltimore at one point. In Detroit, they were allowed, providing no admission was charged. Baseball went so far as to prohibit pitchers from throwing the spitball, as a sanitary precaution.

It was a time before social distancing as many infected people continued to comingle with others, in turn unwittingly contaminating them. Kimbro, an army private serving with 52 Company, 13th Training Battalion, 153rd Depot Brigade, was one such person doomed to catch the disease.

The young ballplayer fell deathly ill and, on Sept. 19, succumbed to bronchial pneumonia caused by influenza. Only 23 at the time of his demise, we’ll only be left to wonder how brightly his star could’ve shined on the baseball diamond.

While in France with the 807th Power Infantry, Webster also fell to influenza-like millions of other souls. Serving his country as Kimbro did, he died two months after his friend. Thirty-four years later, he received some recognition of his accomplishments on the baseball field — he was listed on a player-voted poll in the 1952 Pittsburgh Courier as one of the Negro Leagues’ best players ever.