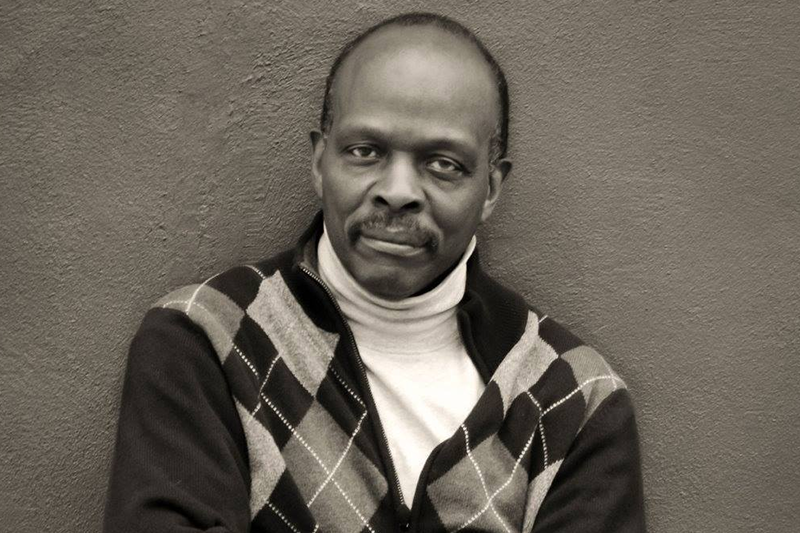

Co-curated by the artistic director of Studio@620 Bob Devin Jones, the Dali Museum’s exhibit “Aimé Césaire: Poetry, Surrealism, and Négritude,” is on view until Dec. 5.

By J.A. Jones, Staff Writer

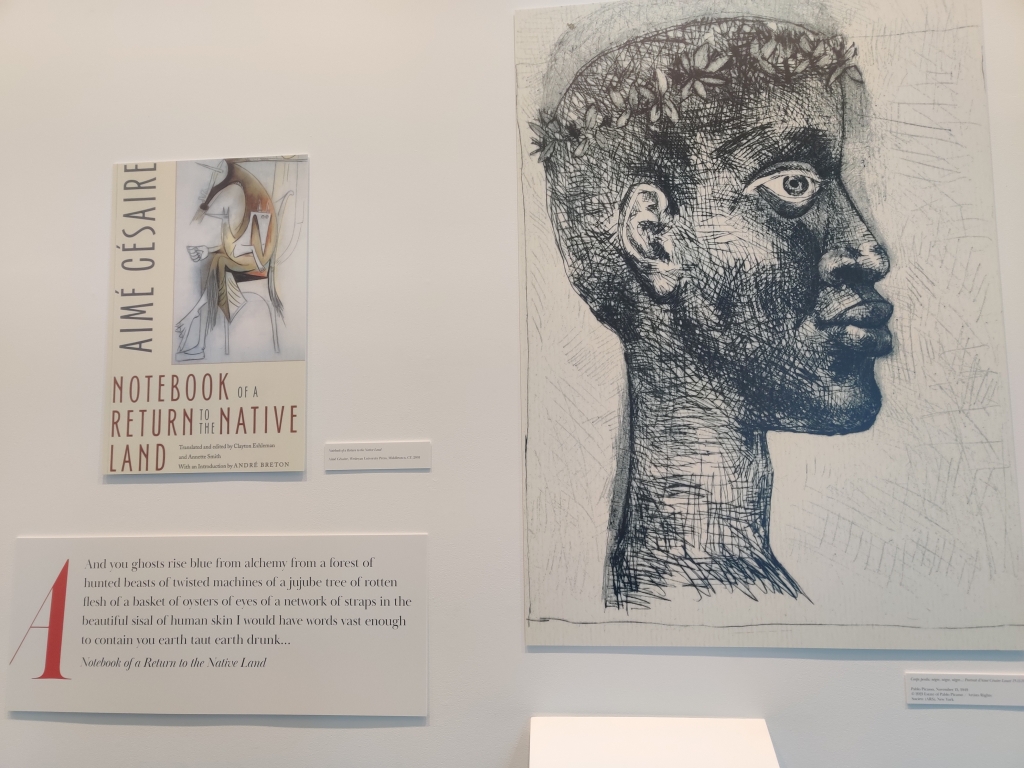

ST PETERSBURG – The Dali Museum’s exhibit “Aimé Césaire: Poetry, Surrealism, and Négritude,” on view until Dec. 5, reviews the life of the surrealist poet and politician from the French Caribbean island of Martinique.

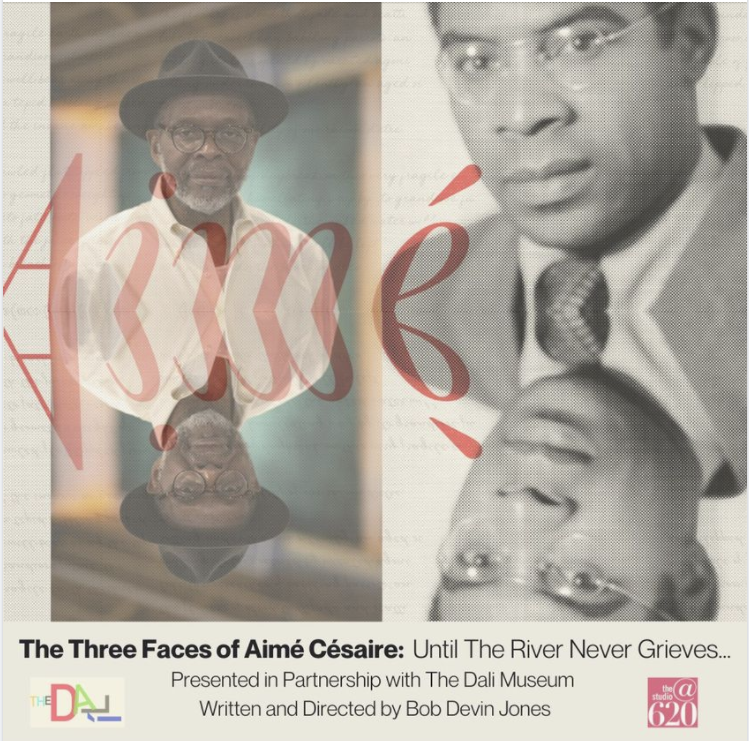

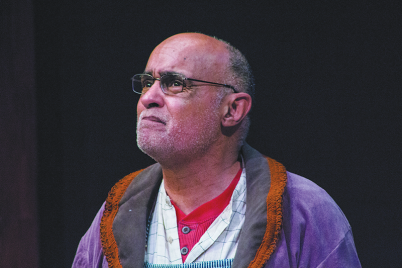

Co-curated by Bob Devin Jones, artistic director of Studio@620, the exhibit features a performance by Jones and others, “Until the River Never Grieves.” While sold-out at the Dali on Oct. 11, the evening of poetry, dance and music will also be performed at the Studio@620 on Oct. 13-14 at 7:30 p.m.

Césaire was born on June 26, 1913, in the small coastal town of Basse-Pointe on the French-Caribbean island of Martinique. One of seven children, he learned to read and write early and excelled in school. After receiving a scholarship in the 1930s, he traveled to Paris to attend prestigious liberal art schools, including École Normale Supérieure, one of the country’s major universities.

While there, he met Leopold Senghor, who would later become the first president of Senegal, and Guyanese poet and politician Léon-Gontran Damas. With them, Césaire founded the journal “L’Etudiant noir” – The Black Student.

During these years, Césaire coined the term Négritude, which he defined as “the simple recognition of the fact that one is Black, the acceptance of this fact, and of our destiny as Blacks, of our history and culture.”

For Césaire and his wife Suzanne, with whom he founded the anti-colonialist surrealist journal “Tropiques,” and other students and intellectuals living during the years of Nazi occupation, the surrealist movement, most often understood through the experimental paintings of Salvador Dali, was really about “freedom.”

Césaire linked his philosophy of negritude – “Black consciousness” – to the surrealist movement’s abstract visual and theoretical ideas and saw the two movements as compatible. He was quoted as commenting, “Surrealism provided me with what I had been confusedly searching for.”

His work challenged and questioned what colonialism did to the mind and spirit of Black people and how they could regain their footing in hostile, racist environments. But his language, as a surrealist, was complex, full of symbols, dreamy, and subverted meaning instead of directly criticizing regimes or political leadership.

The poet-philosopher went on to become elected to the top governmental of Martinique, serving as mayor for 17 years before retiring. He died in 2008 at the age of 94 and has been recognized as one of the most influential artists and intellectuals of his time.

Jones’ performances of “Until the River Never Grieves” (the name of one of Césaire’s poems) weave the poetry of Césaire along with dance, music, Jones’ poetry, and several dancers and other performers.

For Jones, approaching Césaire’s work meant not considering it in an “Aristotelian or Socratic” way of asking a lot of questions and doing theoretical research — but in a way that would allow him to “jar the floor.”

Using Césaire’s poetry from the book “Lost Body” written alongside art by painter Pablo Picasso, the theater director, performer, and playwright knew he would need a more expressive take on the work.

In other words, for Jones, if the poems in “Lost Body” reflected the “displacement” of Black people – whether from the continent by slavery, colonialism, or by psychic loss of identity of self, all of which Césaire’s poems seem to cover — it needed to be a theatrical experience.

For Jones, he needed a way to enter the work and share it with viewers, which would allow him to “stomp, stomp, and stomp again.” He mentioned Ntozake Shange’s influence – the writer, director and performer of the theatrical classic “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When The Rainbow is Enuf.” Shange is credited with creating the choreopoem form melding poetry and dance, in the same way Jones does in “Until the River Never Grieves.”

Jones noted that “the first thing that inspires me about his (Césaire’s) poems — and which is why I don’t call myself a poet, although I’ve written several poems — is that a good poem leads you through its labyrinth, and then at the end, it brings it all together, and it makes you reflect on yourself, and makes you catch your breath.”

Jones said the poems in “Lost Body” often seem to revolve around the question of “how do you get back home.” And importantly, said Jones, he found that in Césaire’s work, “no matter what the subject matter, gets me home.”

Jones will perform “Until the River Grieves” with three performers and musicians, at the Studio@620, on Oct. 13 and 14; the exhibit at the Dali is on until Dec 5.