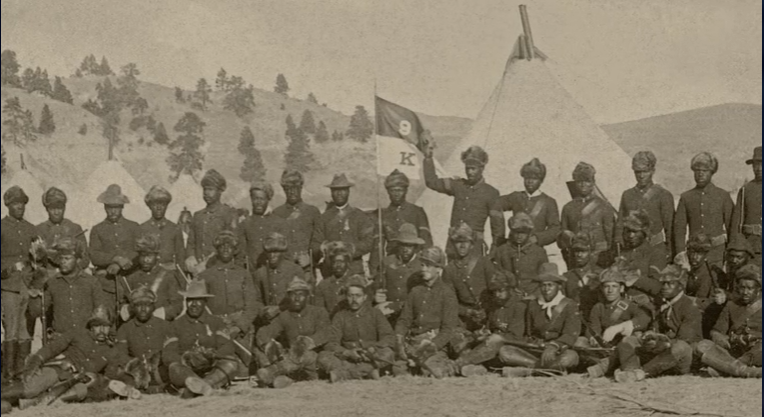

The Buffalo Soldiers were Black troops who were veterans of the Indian Wars. The indigenous populations who fought against these soldiers referred to the Black cavalry troops as “buffalo soldiers” because of their dark curly hair, which they felt resembled a buffalo’s coat and fierce fighting nature.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

The PBS documentary “Buffalo Soldiers: Fighting on Two Fronts” depicts the plight of African-American soldiers in this country as they fought military conflicts abroad and civil rights struggles at home.

The Buffalo Soldiers were Black troops who were veterans of the Indian Wars, explained author and park ranger Shelton Johnson in the documentary. Soldiers from the Deep South, these men sought refuge in the military.

The now little-known history of the Buffalo Soldiers stretches from what came to be known as the Indian Wars in the late 19th century through the end of racial segregation in the U.S. military following the Korean War.

The indigenous populations who fought against these soldiers referred to the Black cavalry troops as “buffalo soldiers” because of their dark curly hair, which they felt resembled a buffalo’s coat, and fierce fighting nature. The nickname soon became synonymous with all African-American regiments formed in 1866.

But the Native population didn’t necessarily see the Buffalo Soldiers as heroes, said Professor Quintard Taylor, Ph.D., University of Washington.

“They all came to the conclusion that if you fight for the country, you should be a full-fledged citizen. That’s what drove Buffalo Soldiers to fight even knowing that the United States might not honor that promise.”

In the narrative of American history, the West has always been this mythical and symbolic place in which heroic deeds were done, and being capable of great deeds was not something that society was willing to admit that Black people were capable of doing, said Darrell Millner, emeritus professor of Black Studies at Portland State University.

The first part of the Buffalo Soldiers’ story takes place in the West, as the United States expanded into Indigenous lands.

“And so, as a consequence, when we tell our stories, we leave the Black stories out, and the Buffalo Soldiers were a perfect example of that,” he said.

Perhaps the best example of this crossing-out of Black stories comes from the Spanish-American War, the documentary points out, when the U.S. intervened in the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain. The explosion of an American battleship, the U.S.S. Maine, in Havana’s harbor roused public support for war.

“We go to war with Spain in 1898 to conquer Cuba and Puerto Rico, and eventually, that culminates in one of the most famous battles of American military history, the Battle at San Juan Hill,” Millner said.

Black soldiers made up about 3,000 men, or 13 percent of the U.S. troops sent to Cuba. The brief Spanish-American War lasted roughly six months, but it was enough to promote the career of a little-known New York City politician, Theodore Roosevelt.

“Roosevelt was a prima donna,” Taylor explained, adding that he had never been in the military. He literally “organized the Rough Riders out of whole cloth despite the fact that he had no military background, and he sort of pushed his way in to lead the Rough Riders in Cuba.”

“We’ve all heard the story of Teddy Roosevelt charging up San Juan Hill,” historian Anthony Powell said. “Now the real story: they charged up San Juan Hill after the 10th Cavalry had breached the defenses.”

A Black soldier, Sergeant George Barry of the 10th Cavalry, planted the flags atop the hill. Roosevelt and his men arrived well after the 10th and the 3rd Cavalry, a white regiment.

Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders charged up San Juan Hill after the all-Black 10th Cavalry had breached the defenses.

Quoted in the “Tampa Morning Tribune,” Sergeant Louis Bowman, 10th Cavalry, said: “If it had not been for the timely aid of the 10th Cavalry, the Rough Riders would have been exterminated.”

After the battle was over, there were all the official photographs, and the photograph that we most see now in classrooms is Theodore Roosevelt standing in the middle and his Rough Riders all around him, Taylor pointed out.

“If you extend that photograph out, then you’ll see the Black soldiers,” he said, “and in a way, that’s a metaphor for what happened on San Juan Hill. That it is assumed that Theodore Roosevelt led the Rough Riders up, they were the ones who defeated the Spanish, and that broke the back of Spanish resistance and led to the American victory. In fact, it was a victory that belonged as much to the Buffalo Soldiers.”

The now little-known history of the Buffalo Soldiers stretches from what came to be known as the Indian Wars in the late 19th century through the end of racial segregation in the U.S. military following the Korean War.

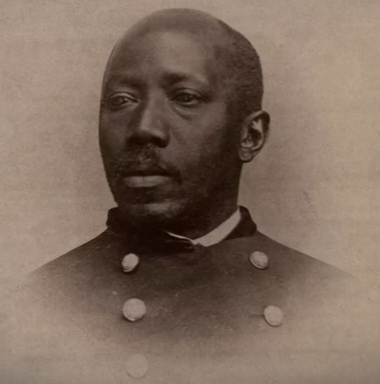

Colonel Charles Young was one of the first Black graduates of West Point.

The Buffalo Soldiers were all-Black cavalry and infantry regiments. The first part of the Buffalo Soldiers’ story takes place in the West, as the United States expanded into Indigenous lands.

This story is embodied by men like Ordnance Sergeant Moses Williams, a Medal of Honor recipient, the documentary explains.

The second part of the Buffalo Soldiers’ story picks up as Indigenous people are being forced onto reservations, and the United States begins engaging in military expeditions abroad in Cuba, the Philippines and Mexico.

This story is embodied by Lieutenant Colonel Charles Young, one of the first Black graduates of West Point.

“In every American war– the American Revolution, War of 1812, the Civil War– all of those have included large involvements of African Americans,” Millner said.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, abolitionist Frederick Douglass lobbied the Lincoln Administration to accept Black men into the Union Army. Black physician Martin Delany recruited thousands of Black men, who was commissioned as a major to lead the United States Colored Troops.

By the time the war ended in 1865, 40,000 African-American soldiers had died to help keep the nation whole.

Delany’s comments in 1865 are quoted in the film: “Do you know that if it was not for the Black men, this war never would have been brought to a close with success to the Union?”

President Abraham Lincoln agreed, as he wrote: “Without the military help of the Black freedmen, the war against the South could not have been won.”

At the end of the war, the United States Colored Troops were disbanded. Wartime casualties had reduced the U.S. Army to a fraction of its former size.

Black physician Martin Delany recruited thousands of Black men

“It isn’t until the end of the Civil War that the nation’s energy shifts, and they’re suddenly interested in Western land and expansion,” said Upper Skagit Tribe member Ryan Booth, Ph.D., Washington State University. “Manifest Destiny, extending America from shore to shore, from sea to sea, was kind of an official policy, but it was also an attitude. Most people forget that we are on lands that once had all of this rich Native American life. That there were people who were living and dying and being born on these lands.”

For the quest for continental expansion to succeed, the Indigenous people who had lived on the land for thousands of years had to be dealt with. Railroads were cutting through Native homelands, creating conflict. “Indian removal,” as it came to be called, required a larger military force. In 1866, Congress authorized the formation of 30 new units.

“That included two African-American cavalry units and four African-American infantry units,” Millner said.

Many of the veterans of the United States Colored Troops would become the nucleus of the soldiers that enlisted in the six Black regiments after the Civil War, Powell explained. Going into the army was all about making money for a young Black man.

Moses Williams contracted smallpox, leaving him with no vision in his left eye, but he was still an extraordinary marksman.

“If you’re poor, if you’re a sharecropper’s son, that $13 a month sounds pretty good,” Johnson said.

You have to remember that although Blacks were now newly free — the adoption of the 13th Amendment had abolished slavery — their real condition in the American South had not changed that much, Millner said. They had no property; they had no money; they had no political power.

“They come from a background where it was illegal to teach an enslaved person to read or write,” Johnson said. “If you tried to vote at that time, there were literacy tests that were put in front of you, and they were designed so that you would fail that test.

“And if you could pass the literacy test, if you could pay for the poll tax, you had to deal with outright intimidation at the polling place. All of these barriers were put in front of them, but which road was clear and open? And that was the road to enlistment.”

Powell shared that when he was a child, he was very lucky to have a grandfather who had been a Buffalo Soldier. His name was Samuel Nathanial Waller, and he joined the army in 1887 and retired in 1927. He died in 1979 at 105.

“I asked him one time,” Powell recalled, “I said, respectfully, ‘How come you served this racist country for 40 years?’ And my grandfather told me something that it took me a while to appreciate. He said the army gave him the only part of the American Dream that the nation would let him share in. The army offered to them something that outside of its structure didn’t exist: an opportunity to advance, an opportunity to grow. That is why many of them joined.”

Samuel Nathanial Waller

In October 1866, in Lake Providence, La., dozens of Black men showed up to join the 9th Cavalry. One of them was 21-year-old Moses Williams. What he describes as “smallpox when I was 20 years old” left him with almost zero vision in his left eye, which makes his later reputation as a skilled marksman extraordinary.

When Williams enlisted, he could not read or write. Service in the army allowed him to start educating himself. The soldiers got meals, uniforms, pensions, and benefits, but Black soldiers could only rise as high as sergeant at that time. The ranks of lieutenant and above were held by white officers.

In Missouri, another formerly enslaved person chose to enlist under the assumed name of William Cathay because she was female. She was born Cathay Williams in Independence, Miss., in September 1844.

During her two years of service, Cathay Williams fought as a man, William Cathay, assigned to Company A of the 38th Infantry

“There were few opportunities for aspiring young Black women in this time period beyond marriage or beyond domestic service to white society,” Millner said.

Once owned by a wealthy farmer, Cathay was liberated by the Union Army, but pressed into service as war contraband. The 22-year-old had no experience as a cook and was soon reassigned to the laundry, exploited by the Yankees as she had been by her former master.

After the war, used to military life, she disguised herself as a man to enlist in the Regular Army near St. Louis on Nov. 15, 1866. “William Cathay” passed a clearly superficial examination and is assigned to Company A of the 38th Infantry.

During her two years of service, Cathay Williams and her unit marched roughly 1,000 miles on foot, from Fort Harker in Kansas to Fort Bayard in New Mexico Territory, enduring extreme weather, meager rations and primitive living conditions.

“The conditions in which they served were terrible,” Powell explained. “You had so many soldiers dying, so many soldiers being disabled because of cholera and different types of diseases.”

After several hospitalizations for rheumatism and neuralgia, Cathay’s sex was finally discovered by an army surgeon. She was discharged on Oct. 14, 1868. Cathay Williams discarded her male disguise upon her discharge and struck out for Colorado, where she worked as a cook and laundress. Stricken with diabetes and neuralgia, she applied for an army pension but was refused. She died in Trinidad, Colo., in 1893, at 48.

Next week, we’ll learn more about the Buffalo Soldier in the lawless Wild West.

All historical photos used in this article were taken from the documentary “Buffalo Soldiers: Fighting on Two Fronts.”