BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

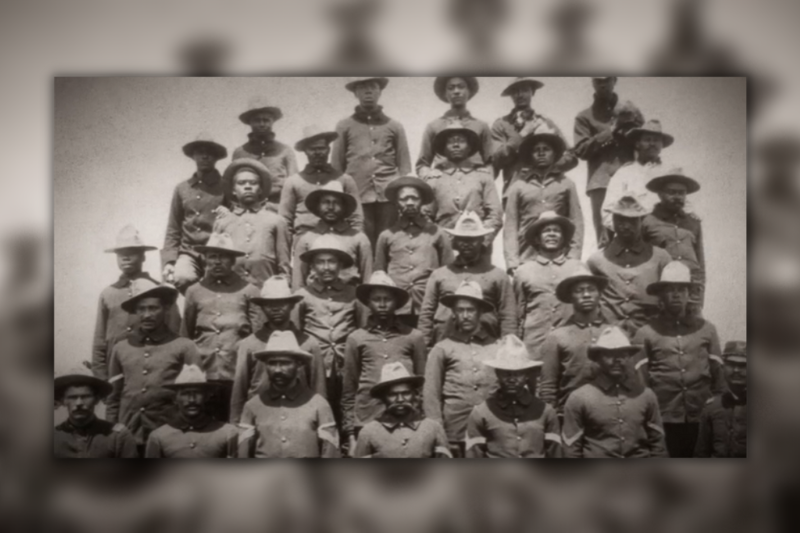

The PBS documentary “Buffalo Soldiers: Fighting on Two Fronts” depicts the plight of African-American soldiers in the United States as they fought military conflicts abroad and civil rights struggles at home.

In part one of this summary, we learned about the first part of the Buffalo Soldiers’ story, which took place in the West as the United States expanded into Indigenous lands.

We pick the second part of their story up as the Indigenous people are being forced onto reservations with the help of the Buffalo Soldiers.

The Wild Wild West

Of the six new regiments of Black soldiers created in 1866, after the Civil War, two were ordered to Texas, one to New Mexico Territory and the others to Kansas and the Indian Territories in present-day Oklahoma. Only two were initially stationed outside the West, and even those regiments would soon be posted to the frontier.

“The American West was a very difficult, hostile place to live at this time, whether you were engaging in combat or not,” said Darrell Millner, emeritus professor of Black Studies at Portland State University.

Mexican bandits and white outlaws operated freely on both sides of the Rio Grande, and bands of Kiowa, Comanche and Mescalero Apache tribes raid across West Texas. The Buffalo Soldiers served as a police force in what was literally the Wild West.

Moses Williams contracted smallpox, leaving him with no vision in his left eye, but he was still an extraordinary marksman.

Ordnance Sergeant Moses Williams and the 9th Cavalry will spend the next decade in Texas. They ranged out on patrol for as much as a year at a stretch, but many Texas citizens did not welcome the Buffalo Soldiers despite their role in securing the frontier.

“Think of the irony here,” said Professor Quintard Taylor, Ph.D., University of Washington. “Black people were being attacked in East Texas by Ku Klux Klan types. Black people in West Texas are defending whites from Native Americans.”

The Blacks who had to coexist in those Western outposts would be surrounded by former Confederates who would look upon a Black soldier as not a whole human being and would not be willing to treat a Black soldier the same way that they would treat a white soldier or a white citizen, Millner said.

When the 9th Cavalry first arrived in Texas, a white company commander, Lieutenant Edward Heyl, ordered several of his men to be hung by their wrists from tree limbs when they did not respond quickly enough to his orders. Heyl’s brutality resulted in a mutiny. Two officers were killed, and several soldiers were court-martialed and jailed. Heyl got off with a reprimand.

There’s controversy about how the Buffalo Soldiers got the name “Buffalo Soldier.” As early as 1872, soldiers’ letters reference the term “Buffalo Soldiers.”

“The Plains Indians, the Lakota, Dakota, Sioux, the Cheyenne, they saw these African- American soldiers, and because of their ferocity in battle and the texture of their hair, they began to call them “Buffalo Soldiers” as a term of respect,” Johnson said.

Another possible explanation is that the name could have come from the heavy buffalo robes that soldiers wore in the winter, but regardless of its origins, the name “Buffalo Soldiers” stuck.

“And so, it was the name that they adopted for themselves and held with honor well into the 20th century,” Millner said.

Indian Wars

Soon after his 1866 enlistment, Moses Williams was promoted to first sergeant. He would have been both an adviser to his commanding officers and a mentor to men of lower rank. The role of sergeant was vital in an army company. The sergeant not only helps oversee the daily activities of those soldiers but also is that conduit above the white officers.

On May 20, 1870, Williams ordered one of his men, Sergeant Emanuel Stance, to pursue a group of Apache near Fort McKavett. They evidently meant to capture the stock. For his bravery in this engagement, Stance became the first Buffalo Soldier awarded the Medal of Honor.

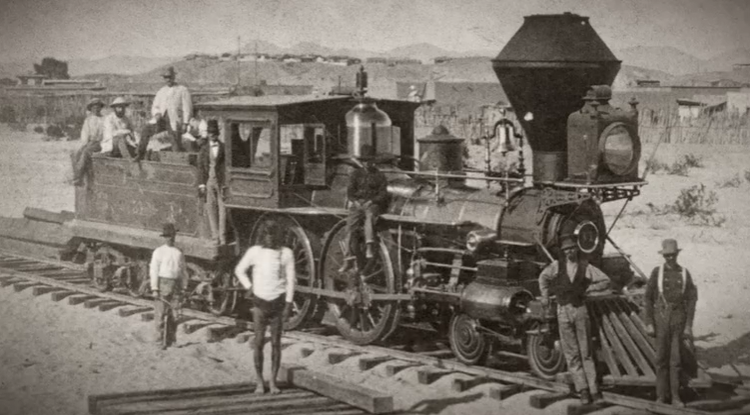

The day-to-day work of African-American soldiers was escorting supply wagons, helping string telegraph lines and helping protect parties that were surveying locations for railway lines.

Life at a typical Western army post would have been a hub of activity. The day-to-day work of African-American soldiers was escorting supply wagons, helping string telegraph lines and helping protect parties that were surveying locations for railway lines. All this expansion into the American West was coming at the cost of displacing Native peoples and their lifeways.

The Buffalo Soldiers were largely on the front line of that conflict.

“We look back, and we see two populations of color, so we assume there would be some kind of potential alliance,” Millner said. “The Buffalo Soldiers did not look at the Native Americans and see another, in quotes, ‘Colored population.’ They saw a designated enemy.”

They didn’t join to kill Indians, Johnson explained.

“They joined because it gave them a sense of respect to wear the uniform of the United States, to potentially sacrifice their life for the United States in the hope that that sacrifice would result in conditions improving for their loved ones back home,” he said.

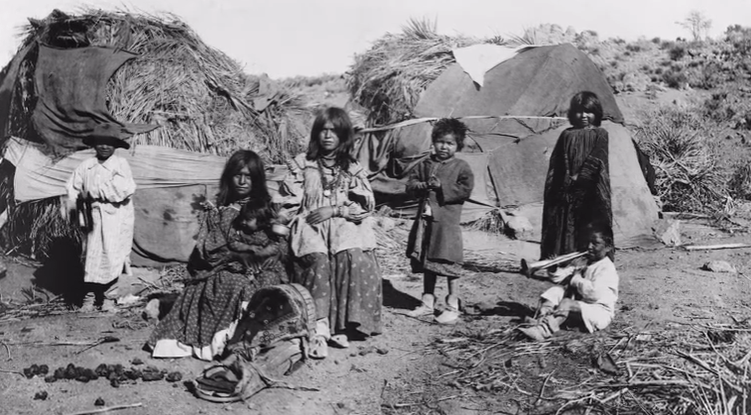

On the one hand, it is a story of great triumph, Upper Skagit Tribe member Ryan Booth, Ph.D., Washington State University averred, but it’s also a story about people being dispossessed.

Expansion into the American West was coming at the cost of displacing Native peoples and their lifeways.

“It’s a story about violence,” he said. “Part of the legacy of the Indian Wars is one of total war. The U.S. Army attempted, in its own way, to starve, kill, maim, do whatever they could to be able to get the end that they wanted.”

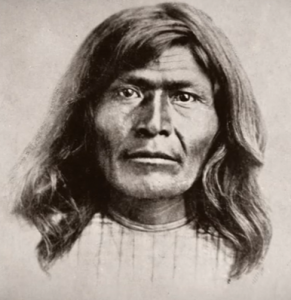

After a decade in Texas, Moses Williams and the 9th Cavalry were ordered to New Mexico Territory. The Buffalo Soldiers set out to track down a group of Apache led by the charismatic warrior Victorio.

“Victorio is probably one of the most brilliant tacticians of the war,” Booth said. “And so, he does this hit-and-run campaign across the American Southwest and into Mexico.”

The 9th Cavalry pursued Victorio for more than a year. In 1880, the 10th Cavalry joined in the chase as American and Mexican officials wanted to see the Apache crushed. The Mexican army finally caught up with Victorio at Tres Castillos.

“He ends up being pursued like a dog,” Booth said. “Ends up dying to try to achieve freedom for his own people.”

Forty of Victorio’s followers escaped, including a respected elder known to his people as Kas-Tziden and to outsiders as Nana. He was 75 years old and crippled in one leg. On Aug. 16, 1881, I Company of the 9th Cavalry — where Moses Williams served as First Sergeant — came into contact with Nana’s band in northern New Mexico.

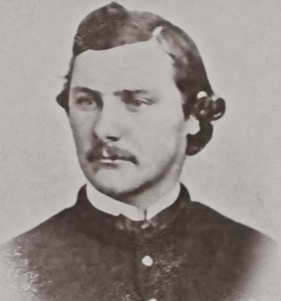

It would prove to be a pivotal day in Williams’ life and career. Williams’ commanding officer was Lieutenant George Burnett, a recent West Point graduate without much field experience.

“So, you really have him looking toward Moses Williams for support and leadership,” said historian and author Greg Shine.

Burnett described Williams and Private Augustus Walley as “the two men who are always by me in every danger.” Burnett describes the day’s events: “It was practically a running fight which continued for several hours, and we had driven the Indians eight to 10 miles into the foothills of the Cuchillo Negro Mountains when they made a final and determined stand.”

Private Augustus Walley was decorated with the nation’s highest military award for their bravery during the Battle of the Cuchillo Negro Mountains.

As they attempted to cut off an Apache retreat into the mountains, Sergeant Williams spotted a potential ambush, an Apache warrior in hiding. When Lieutenant Burnett dismounted and fired, warriors started shooting from the ridge.

“The commanding lieutenant’s horse takes off and flees to the rear,” Shine said.

As they charged back into battle, Burnett realized three privates had become stranded. Private Walley mounted and galloped to him while Burnett and Sergeant Williams were exposed to the fire of at least 25 or 30 Indians without the slightest shelter whatsoever.

“Moses Williams, Augustus Walley and their commanding officer bring these abandoned soldiers to safety in great peril and almost the cost of their own lives,” Shine said.

The horrors of West Point

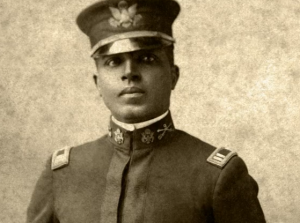

While Moses Williams battled in the Indian Wars, the first generation of Black cadets fought discrimination at the United States Military Academy at West Point. One of those first cadets was Charles Young. Born into slavery in Kentucky, Young’s parents fled with their infant son to Ohio and freedom in 1864. Young’s mother, Arminta, was one of the rare enslaved people who had found a way to educate herself.

“And really was somebody that passed on to Charles Young the importance of education and what an education could do for a Black person,” Charles Young’s biographer Brian Shellum said.

Soon after they arrived in Ohio, Young’s father, Gabriel, joined the 5th Colored Heavy Artillery and served for a year in the Civil War.

“He loved the army, and he loved what it did for him,” Shellum said, “and he passed that on to his son Charles. It was one of the major reasons why Charles Young went to West Point.”

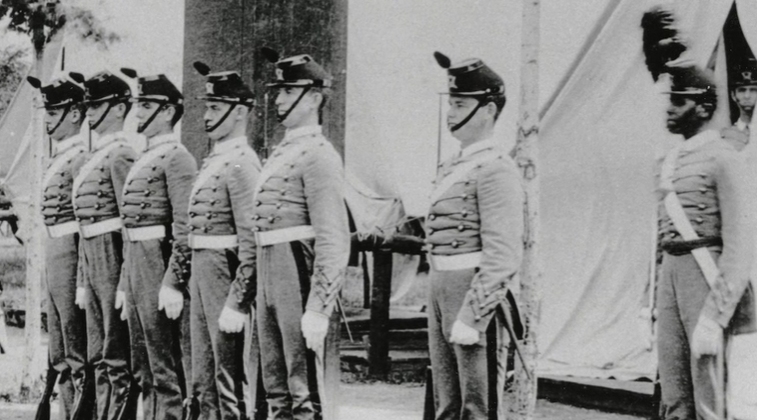

Young was admitted to West Point in 1884. Shellum noted that when Young attended West Point, it was a very difficult place, a place that reflected the Jim Crow norms of society at the time.

“Between 1870 and 1900, 12 Blacks had been admitted to West Point,” Millner said, “but because of almost unimaginable harassment and discrimination, nine of the Blacks were forced to leave before they graduated.”

While at West Point, Young had to learn how to navigate a color line with the other white cadets.

“His experience at West Point was so intense, so severe; he once said the worst thing he could ever wish on an enemy would be to make them a cadet at West Point,” author and park ranger Shelton Johnson said.

Young was the third Black graduate of West Point, in 1889, and he was the last Black graduate until 1936, a period of almost 50 years, Shellum said.

Enlisted men like Moses Williams did not get a formal education like Charles Young did at West Point. But the army needed skilled clerks and assigned its regimental chaplains to attend to the soldiers’ spiritual and educational needs.

“Educational opportunities were really limited for African-American men at the time, and so the army offered this opportunity,” Shine said.

Between 1870 and 1900, 12 Blacks men had been admitted to West Point, but because of almost unimaginable harassment and discrimination, nine of the men were forced to leave before they graduated.

With the encouragement of his regimental chaplain, Williams studied to become an ordnance sergeant, the officer in charge of arms and ammunition at an army post. Williams passed the test and became one of the first Black ordnance sergeants in 1886.

He then transferred to the 25th Infantry to take charge of the ordnance at Fort Buford in the Dakota Territory — a remarkable achievement for a man who could not read or write when he joined the army.

Three years later, in 1889, Charles Young graduated from West Point. The racial barriers that he had overcome as a cadet would shape the rest of his career.

“The army was preoccupied with minimizing Young’s contact with white troops and white officers,” Shellum said. “This meant that when he graduated from West Point, the army had one choice: assign Charles Young to one of the four Black regiments.”

Lieutenant Young is assigned to the 9th Cavalry, Moses Williams’ old unit, and posted to Fort Robinson, Neb. America’s campaign to usurp Indigenous lands was almost finished. Indigenous people had been forced onto reservations, like the Sioux reservation north of Fort Robinson, and the U.S. Army was tasked with ensuring they didn’t leave.

“These larger posts like Fort Robinson were connected by railroad, by telegraph,” Shellum said. “The posts just weren’t isolated like they had been in the former frontier time.”

It was a lonely life for Young as a Black officer.

“As an example, say there was a mandatory function at the officers’ club,” Shellum said. “Charles Young would show up, stay for what he felt was an appropriate time, and excuse himself. He had to stay on his side of the color line.”

Corporals or privates that were well beneath his rank would not necessarily salute him because that meant saluting him, a Colored man, and Euro-Americans at that time did not show deference to any African American, Johnson said.

In 1894, the army reassigned Lieutenant Young to Wilberforce University in Ohio. Unlike his experience of social isolation in the West, at Wilberforce, Young quickly became accepted as part of a vibrant Black intelligentsia.

“He developed a friendship with W.E.B. DuBois, who was assigned as a professor at Wilberforce University at the time,” Shellum said. “DuBois’ biographer calls it the first genuine male friendship that DuBois ever had in his life.”

Young was also reunited with his mother, Arminta, and purchased a house for his family that he called Youngsholm, which would remain a refuge for the rest of his life.

The battle for recognition

In 1895, Moses Williams’ final posting was to Fort Stevens, Ore., where the Columbia River meets the Pacific Ocean. The old Civil War fort is being modernized, and he is the only soldier still stationed there. With no soldiers to command, Williams has one last battle to fight: the battle for recognition.

During the summer of 1896, he receives news that galvanizes him into action.

“Through his correspondence, he learns that at least one of his former fellow soldiers has received the Medal of Honor, and he realizes, well, he was in the very same action,” Shine said.

Private Augustus Walley and Lieutenant George Burnett had both been decorated with the nation’s highest military award for their bravery during the Battle of the Cuchillo Negro Mountains.

“At the time, the way that the Medal of Honor process worked, a soldier could self-nominate, provided that they had the support of their commanding officer,” Shine said. “Moses Williams tracks down his commanding officer, who had since retired and was living in Germany, who writes a very descriptive letter.”

Burnett wrote: “I recommend Sergeant Moses Williams for a Medal of Honor for his coolness, bravery, and unflinching devotion to duty in standing by me in an open, exposed position under heavy fire, thus enabling me to undoubtedly save the lives of at least three of our men.”

Moses Williams died on Aug. 23, 1899, and was buried with his sharpshooter’s badge at the Vancouver Barracks Post Cemetery.

On Nov. 23, 1896, the War Department responded with the Medal of Honor, awarded for “most distinguished gallantry in action with hostile Indians in the foothills of the Cuchillo Negro Mountains.”

Moses Williams retired in May 1898 after 37 years of military service and moved to Fort Vancouver in Washington.

“The unfortunate reality for many Buffalo Soldiers was that in spite of the kind of service that they provided, their fate after their military service was generally disastrous,” Millner said. “They did not receive high pay in the military. They were not able to take advantage of opportunities that might have been available to them as civilians. So, as a consequence, once many of their military careers were over, they were in very desperate circumstances. That was the case for Moses Williams.”

Moses Williams died a year later, on Aug. 23, 1899. He was buried with his sharpshooter’s badge at the Vancouver Barracks Post Cemetery.

Next installment, we’ll learn more about the Buffalo Soldiers and their role in the Philippine-American War.

All historical photos used in this article were taken from the documentary “Buffalo Soldiers: Fighting on Two Fronts.”