‘I think as time has gone on, there are more people who recognize the wrongs that have been done in the past, and there are more people with the courage to be vocal in correcting and acknowledging those mistakes,’ said Ennis Davis.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is an ongoing USF research study that addresses the erasure of historic Black cemeteries in the Tampa Bay area. Awarded a USF Blackness and Anti-Black Racism grant in 2020, it consists of faculty, staff, and students from multiple disciplines across USF St. Pete and Tampa campuses.

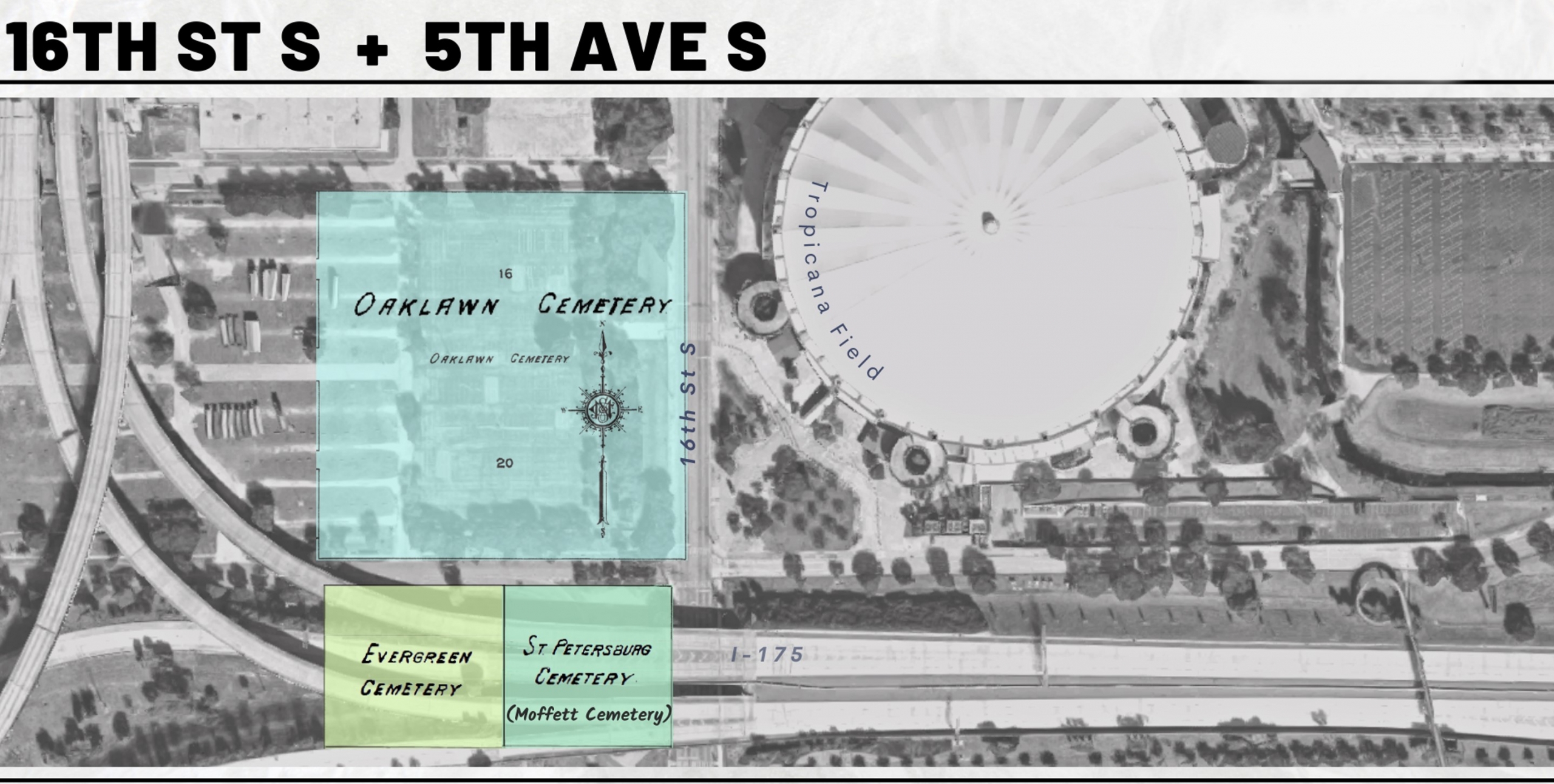

The project focuses on activities to identify, interpret, preserve, record, and memorialize previously unmarked, erased, abandoned, and underfunded African-American burial grounds in Florida, with a focus on Tampa’s Zion Cemetery (located beneath Robles Park Village) and St. Petersburg’s Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries (found beneath a Tropicana Field parking lot and I-275).

One aspect of the African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is recording oral histories of those who remember or are related to those lost to time.

Ennis Davis is a senior planner with Alfred Benesch & Company, specializing in nationwide transportation and urban planning projects. He has written the award-winning books “Reclaiming Jacksonville,” “Cohen Brothers: The Big Store” and “Images of Modern America: Jacksonville.”

Davis, now a Jacksonville resident, was born in Winter Haven in 1977, and his family has been in central Florida for over a century. His great-great-grandfather, a formerly enslaved man named Samuel Davis, migrated from Georgia after the Civil War. He married Ennis Davis’s great-great-grandmother in Live Oak, and by 1900, they lived in present-day Flagler County within the turpentine camp.

“My [maternal] great-grandfather, Franklin Vereen, after the Civil War, migrated from coastal South Carolina to Florida during the 1890s through Central Florida, kind of following the railroads. And by 1925, he lived at 726 22nd St. S, in St. Pete, about four blocks west of Oaklawn and Evergreen cemeteries. He was a physician who operated a sanitorium on 22nd Street South, and he passed in 1925 there. I don’t know where he’s buried; I just know those cemeteries are four blocks away from where he lived.”

Decades later, his father Edwin Davis, Jr. was born in 1945 at Clara Frye Memorial Hospital, a Black hospital in Tampa.

“My great grandad was a McClain, and the McClains were also in this Tampa area, so my family kind of just spreads out the more you dig into history,” Davis said. “But over the years, because my grandad had a bunch of kids because my great grandad had a bunch of kids, they were all in Hillsborough County. Many have lived in Tampa ever since.”

When he was younger, Davis said he and his friends would hang out at Robles Park, constructed in 1951 over Zion Cemetery, believed to be the city’s first African-American burial place.

“I had never heard about Zion until it was reported in the paper. When it was reported in the paper, I looked at the sample amounts, and oh, yeah, there’s a cemetery there.

Davis believes every site must be treated differently based on historical stances, including some of the lost or erased cemeteries in St. Pete.

“You know, the St. Pete sites are parking lots; they’re kind of easier to deal with,” he explained. “With Robles and Zion, you got the projects sitting on part of it, you got, like, a private business or something. Half of it may be on private property, actually, so then you start getting the property rights and all this stuff. But I think at the very least, when you’ve got a site that has been redeveloped with something sitting on top of it, you know if you can acquire that piece of property, then we need to at least memorialize it.”

He added that some sort of “interpretive signage” should be present to share the history. If there is a redevelopment of the grounds in the future, the Zion property needs to be green space too, he said, that memorializes and honors the people still buried under the foundation of those buildings today. Issues, like lost or erased cemeteries, exist to this day because of racism, Davis believes.

“So even today, we don’t have full representation, from a cultural aspect, of what happens in communities like this which leads them to sites like this being buried and redeveloped … the more inclusive and equitable we can be with history and allowing people in the community to have a seat at the table, the better we will be. If we don’t have that seat at the table, then we’ll typically be the mule,” Davis said.

The role of the church has generally changed, or that of the Black church has generally changed since desegregation, Davis asserted.

“When Zion was present when you could actually see it, the church at that point in time would have been the social center, the community center; it would have been the social anchor of the community that it served,” he said. “The church isn’t necessarily that today. Church attendance has declined across the U.S. A lot of churches are just trying to survive. You’ve got to pay for that 100-year-old roof on the building because the collection plate isn’t as thick as it used to be.”

Concerning cemeteries such as Oaklawn, Evergreen, and Moffett in St. Pete, Davis recalls that they were not too far from where his family attended church.

“My dad, during the 1960s, attended college briefly at Gibbs Junior College at 44th Street South,” he said. “I guess during that time he attended church at 20th Street Church of Christ, which is not too far away from where those cemeteries would have been … so, I just kind of remember the neighborhood from the ’80s and the ’90s, kind of attending that church.

Davis’s father attended Gibbs Junior College in the mid-1960s, right before it transitioned into St. Pete Junior College, then transferred to Florida A&M University in Tallahassee. The elder Davis spoke about how vibrant 22nd Street South really was.

“You know, one of his favorite restaurants to eat at every Thursday night was called Geech’s Bar-B-Q,” Davis recalled. “And he talked about how Mr. Geech was well known for mustard-based barbecue sauce, and like every Thursday, he had to get his barbecue from there. So that was pretty cool, listening to that.”

An urban planner by trade and history buff, Davis learned about the cemeteries Evergreen, Oaklawn, and Moffitt being built over and erased by the Tropicana Field parking lot and the interstate. He said this practice was not peculiar to St. Pete but was prevalent elsewhere in the state and throughout the South.

“I’ve just kind of seen it all across the state at this point. And you recognize that it’s a part of our story, just being a Black male or a Black resident in the South, a sixth-generation Floridian,” he noted. “And hearing the stories of my grandparents, my great-uncles when they were around, my parent’s generation, they tell you about this stuff from what they remember from the ’40s and ’50s and ’60s, which is more than I’ve ever heard in any public-school history course. And they lived this stuff. So, I knew about some things, and with the cemeteries in St. Pete, they have the Sanborn maps. So, when I was looking for my grandfather’s property, they pop up, they’re there.”

Davis believes the people buried in such cemeteries are ancestors who “through blood, sweat and tears and sacrifice have pretty much given their lives or allowed for my generation to be where we are today.” If it wasn’t for them, he said these neighborhoods wouldn’t exist, underscoring that “some opportunities that we have today would not be around.”

“So, it’s kind of sad when you see, you know, a loved one that has been buried somewhere and that cemetery is paved over or a building sitting on top of it, or something like that and not acknowledging the souls that are six feet under,” Davis said. “So anytime, you know, this is a remembrance project to me, is something that suggests overdue, justified, it can help share the history of the community with people today and generations of the future. And I truly believe to succeed in the future; you’ve got to know where you come from. I mean, that’s just very important.”

Regarding the treatment of these burial grounds in the present, Davis believes that we can honor the past by placing memorial markers on the desecrated site, even if the headstones aren’t there anymore. The injustices done to cemeteries such as Oaklawn, Moffitt, and Evergreen are getting more publicity these days, Davis believes, because times have changed and “race isn’t the taboo thing it was.”

“I think as time has gone on, there are more people who recognize the wrongs that have been done in the past, and there are more people with the courage to be vocal in correcting and acknowledging those mistakes,” he said. “That’s why you see several communities now going back and changing their zoning ordinances, because systemically, public policy was set up against communities like this … is why the cemeteries are what they are today, under expressways, under asphalt, under buildings.

Antionette Jackson interviewed Ennis Davis on Aug. 27, 2021, and Oct. 8, 2021.