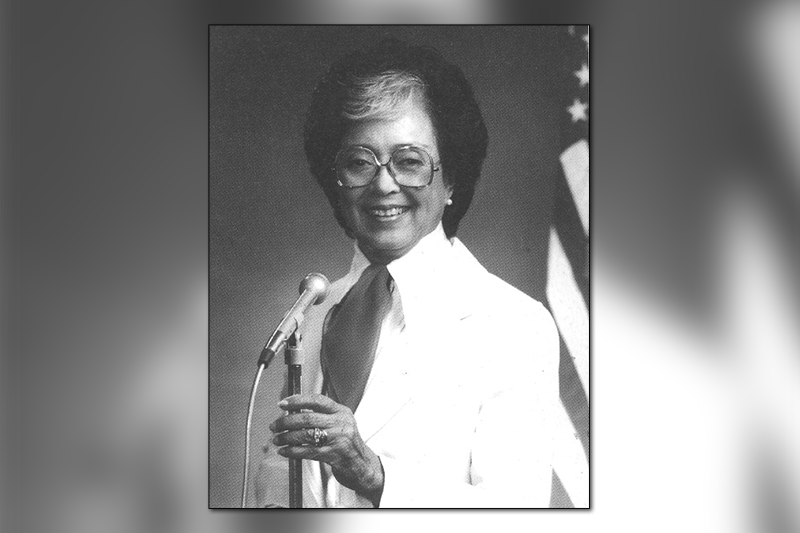

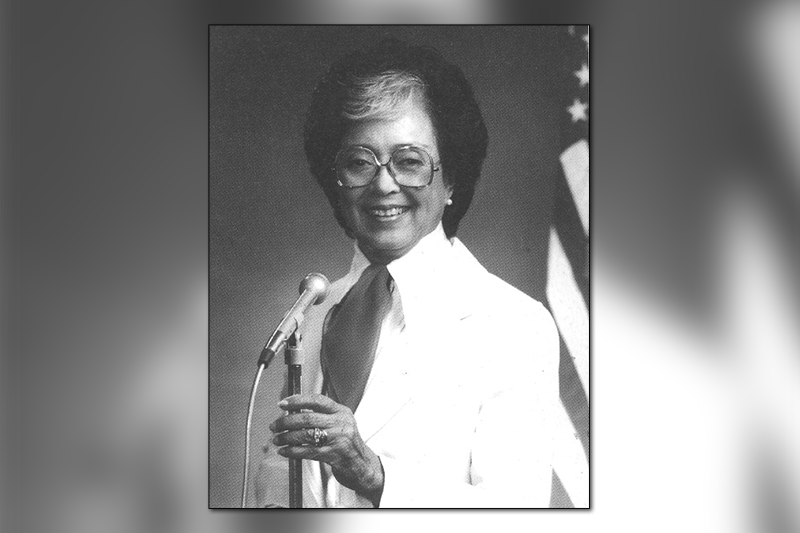

Civil rights trailblazer memorialized

The highway is a portion of I-75 and runs north of Tropicana Field and ends down by the Coliseum. The city council passed the renaming unanimously on July 13, adopting the state law that came into effect July 1 when Gov. Rick Scott signed the transportation package. The Pinellas County Commission gave the go-ahead July 18.

The highway is a portion of I-75 and runs north of Tropicana Field and ends down by the Coliseum. The city council passed the renaming unanimously on July 13, adopting the state law that came into effect July 1 when Gov. Rick Scott signed the transportation package. The Pinellas County Commission gave the go-ahead July 18.