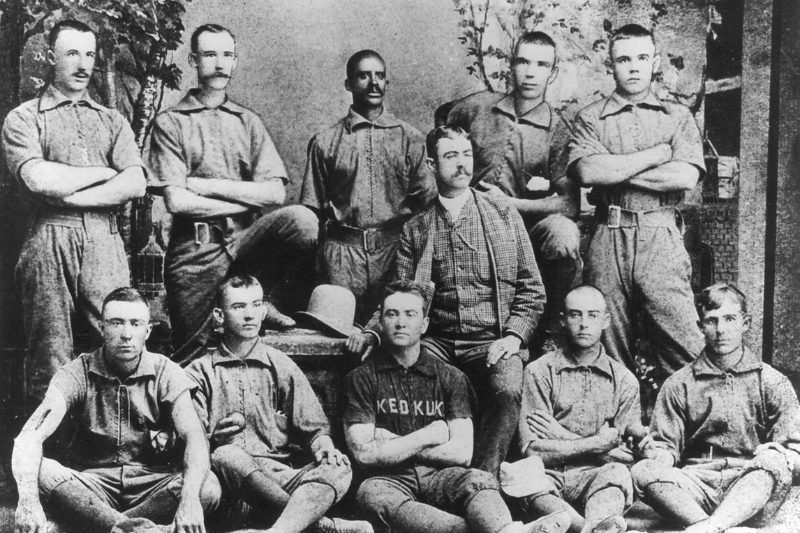

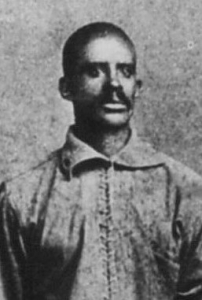

Born John W. Jackson, Bud Fowler was a pioneer in every sense of the word. Not only the first Black pro ballplayer, but he was also the first to play on integrated teams. Fowler (top row, center) with the Keokuk, Iowa team of the Western League in 1885. [Photo: National Baseball Library ]

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

Almost 70 years before Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color line, African-American ballplayer John “Bud” Fowler stepped onto the field one spring day in 1878. Taking his position alongside white players on the diamond, he secured his place in history.

Fowler, widely acknowledged as the first Black professional baseball player, was recently elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., through the Early Baseball Era Committee. As is often the case, fans and critics might discuss the player’s merits and argue whether he deserves the honor.

Statistics are thrown around, arguments are made with pro and con lists and questions concerning his contributions are volleyed back and forth. Yet the only question that flashed in my mind when I heard Fowler had finally been selected to occupy such a hallowed spot among the game’s immortals was this: What the heck took so long?

Bud Fowler was recently elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y.

Born John W. Jackson, Fowler was a pioneer in every sense of the word. Not only the first Black pro ballplayer, but he was also the first to play on integrated teams. All-Black teams of note in the late 1800s were scarce, and Fowler preferred the higher level of competition on white teams. Consequently, in stints with teams from all over the country — including burgs like Stillwater, Omaha, Pueblo, and Binghamton — he became the first African-American player of renown.

Though 19th-century baseball records are notoriously spotty, by most accounts, Fowler, who learned to play baseball while growing up in his hometown of Cooperstown, was an exceptional talent. Playing for Stillwater in the Northwestern League in 1884, he knocked out a league-leading 57 hits — 10 for extra bases — in only 48 games, finishing with a .302 batting average.

In 1890, at the age of 32, he posted a muscular .322 average with a pair of home runs. Although two homers may not sound too impressive these days, Fowler accomplished this feat in the dead-ball era when a batted ball carried about as far as a brick and home runs were a rarity.

Agile and a slick-fielding, he primarily played second base but put in many innings as a pitcher and catcher. All this in a time when the players were so tough that most didn’t even use gloves, catching everything barehanded. The “Sporting Life,” then considered a bible of baseball, praised him: “With his splendid abilities he would long ago have been on some good club had his color been white instead of black. Those who know say there is no better second baseman in the country.”

Not only adept on the diamond, Fowler was also one of the first relevant Black promoters. He organized the first successful Black barnstorming clubs and co-formed the Page Fence Giants in 1894, a professional Black baseball team based in Adrian, Mich. The team only played four seasons but went an incredible 121-31 in their debut year when Fowler played second base and managed.

According to the Negro League Baseball Players Association: “They traveled around the country in a custom-made railroad car that featured sleeping quarters, a cook, and a porter. The railroad car was a part of the attraction as players theatrically emerged from it dressed in full uniform and firefighter’s hats. Then they rode bicycles around each town trying to drum up attendance for the game later that day.”

Fowler traversed the country like few other players in his day, but the fact that he was shipped from team to team had nothing to do with his skills. The mere fact that an African American would take the field with whites so enraged opposing players (and bigoted fans) that he was deemed more trouble than he was worth and was forced to move on. Sometimes, he was given the boot because players on his own team didn’t relish sharing the field with a Black man.

Though Fowler’s love of the game drove him to pursue it as a career, he must’ve realized the obstacles in his path. For one thing, there had been no Black pro ballplayers before him, so we can readily assume his family wasn’t too thrilled about a son trying to become a Black trailblazer in the baseball world — then the exclusive domain of whites. (He’d learned to be a barber from his father and cut hair while on the road to supplement his baseball income.) Moreover, once he found himself on a team’s lineup, the locals were hardly ready to accept him with open arms.

In newspapers, sportswriters referred to him — the sole Black man on his team — as “colored,” “darky,” or “coon.” Along with nasty epithets tossed at him from the stands and opposing dugouts, vicious attacks on the field soon became a very real part of Fowler’s playing career.

He took to playing second base with the lower part of his legs encased in wooden guards to protect himself from players trying to intentionally spike him with their cleats while sliding. According to the St. Paul Daily Globe, one white player did some damage during an 1884 game: “Fowler, the lightning-colored catcher for the Stillwaters, had his foot spiked by a base runner at home plate, breaking the bone of his big toe. The surgeon says it will be several days before he can play again…”

Many pitchers purposely threw at him while he stood at the plate, trying to knock him down. In June of 1884, Fowler was drilled so hard in the ribs with a pitch that he was knocked unconscious and missed three games as a result. Yet he stood firm — at least once, even trading punches with a white player for his dirty playing tactics.

In 1895, he played for Lansing of the Michigan State League, and in 31 games, he hit .331. Though that would qualify as a banner year for any slugger, Fowler instead began to find his options limited. As the turn of the century neared, the color line was becoming bolder around the various pro baseball leagues due to whites’ “gentlemen’s agreement” to keep Black players out.

He wrote in 1895, “My skin is against me. If I had not been quite so black, I might have caught on as a Spaniard or something of that kind. The race prejudice is so strong that my black skin barred me.”

In his later years, his promotional spirit was still strong. He organized the Muncie Londons, a Black club based in Indiana in 1896; became the main promoter and organizer for the Lone Star Colored League of Texas in 1897, and formed a team called the All-American Black Tourists, which would operate under his direction, on and off, through at least 1909.

The most glaring thing missing from his career statistics is a stint in the majors. His natural ability and skill in the high minor leagues, which he flashed year after year with his bat or glove, should have been his ticket to compete at the highest level of play. Racial bigotry made certain he would never make it past the entrance.

His sheer determination to excel in what was then a white man’s game and, more importantly, shine in a white man’s world eclipses even his on-field accomplishments. With his pluckiness, grit, and resolve, he carved out a path for other African Americans to follow and has more than earned his place in the Hall of Fame.

Fowler should be remembered as a baseball Renaissance Man — pioneer, player, manager, team founder, promoter, showman, and even sage, dispensing advice to white scouts who readily sought him to ask about other up-and-coming Black players. He died in 1913 and was buried in an unmarked grave until 1987 when the Society for American Baseball Research purchased a headstone that reads:

“John W. Jackson: `Bud Fowler,’ Black Baseball Pioneer.”

It took well over a century, but now, at least in spirit, he has journeyed back to his childhood home of Cooperstown.

To reach Frank Drouzas, email fdrouzas@theweeklychallenger.com