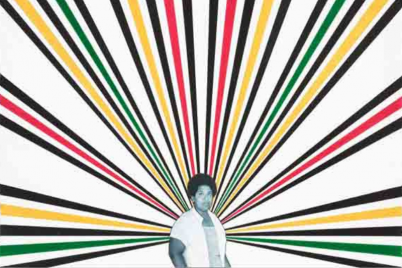

July’s installment of Community Conversations discussed cultural gentrification with Evelyn Newman-Phillips, professor and chair of the Anthropology Department at Central Connecticut State University, Stetson Law School Professor Judith Scully and Professor Deborah E. Thrower with Gwendolyn Reese, president of the African American Heritage Association.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – July’s installment of Community Conversations — a partnership between the African American Heritage Association and Tombolo Books — held a virtual roundtable to discuss cultural gentrification led by Gwendolyn Reese, president of the AAHA.

“Gentrification is a powerful force for economic change in our cities,” said Reese, as defined by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, “but it is often accompanied by extreme and unnecessary cultural displacement.”

While it increases the value of properties in areas that have suffered from long periods of disinvestment, she added, it also results in rising rents and the appropriation of the neighborhood’s history, culture, and heritage.

“Sometimes it can even result in omissions, rewriting and even erasures of the neighborhood’s history,” Reese said.

Evelyn Newman-Phillips, professor and chair of the Anthropology Department at Central Connecticut State University, said when one thinks about gentrification, we often talk about displacement in the physical sense. But we don’t think about the cultural and social implications of what happens when you disrupt people.

She recalled residents of Laurel Park not wanting a new apartment complex in the area, yet within a few years, there were “nothing but apartments and condos going up” in the area.

“What happened to the people? What happened to the culture,” Phillips asked. “And some of those women that I knew, their social network was disrupted. So, when you disrupt people’s social networks, what happens? The person who was going to keep your child but now lives across town — all of these kinds of issues people don’t consider.”

“Race has been the cultural displacement of who you are first,” she added.

Stetson Law School Professor Judith Scully remarked that gentrification changes the neighborhood’s soul.

“Every neighborhood has its own spiritual characteristics,” she said, “and we tend not to pay attention to that, especially when we’re about so-called economic development.”

History can get erased during gentrification, but so can cultural norms, Scully observed. She noted specific communities in New Orleans where African drumming was a part of the neighborhood’s ambiance. When wealthier white people bought property in that area, they complained about the drumming.

“That drumming was a cultural part of that community,” she said. “It was a spiritual connection for the people who lived there.”

Scully and Reese agreed that sometimes pastimes and traditions — whether an African-American man “sitting under the tree” and imparting wisdom to younger generations or women and girls braiding their hair on the front porch — can change when a neighborhood is gentrified.

Undergraduate social work instructor Professor Deborah E. Thrower noted that people of close-knit communities often have “protective factors” that, once stripped away, can make them feel isolated, depressed, and disgruntled.

When we are displaced from these nurturing, safe environments that we created during the Jim Crow segregation and redlining, we are dispersed, Reese pointed out.

“Gentrification also is a form of displacement,” she said. “In many instances, the original residents can no longer afford to live there.”

When our neighborhoods are gentrified, police presence becomes more intense, Reese noted.

“The white people who have moved into a previously all-Black neighborhood bring their fears with them and their issues of safety,” she said, “which causes the police to be harsher to those who, the original residents, are still there.”

When neighborhoods change, those who come into it want to change it to what they want, Reese averred, instead of respecting and embracing what is already there. She noted an instance of neighbors new to an area who complained about the smoke from backyard barbecues and fish fries, even though such gatherings had been going on for years.

“Culture exists to give people a sense of being,” Phillips said, “a sense of belonging, and understanding on how to navigate. So, you disrupt that culture; you cause traumatic issues.”

Fragmented communities can lead to trauma, which can even be a root cause of young people getting involved in criminal activity, she said. Even some of the elderly, who hold out to developers and refuse to sell their homes for as long as they can, will finally give in and move, only to spend their final years unhappy in displacement, Reese noted.

Such an “adjustment disorder,” which is a mental health issue, can come with anxiety, depression, or both, Thrower added.

Concerning the integrity of Black history in this country, Reese said she sees the telling of our stories in conventional, white history books as a form of gentrification in itself. Children can benefit from the continued telling of stories while they’re at church or gathered around someone speaking under the tree, Thrower said. Scully added that even sculptures and public monuments can “preserve our ability to remember, our ability to retell the stories.”

“We really have to as a community to reinvest in our children,” Phillips said, “because we know the things that we had during that Jim Crow period, in those protected environments, those teachers ensured that those kids had their culture that was passed on.”

The panel noted that cultural gentrification and appropriation even include music, fashion, and hairstyles like dreadlocks, which some white people wear without realizing that they symbolize a connection to Africa and pride in African characteristics.

Reese said that teaching children critical thinking in school and how government works is crucial, but it is not happening nowadays.

“It disempowers a people, all people,” she said. “And I think that’s why we see apathy around voting, and we see apathy about many of the issues we’re talking about today.”