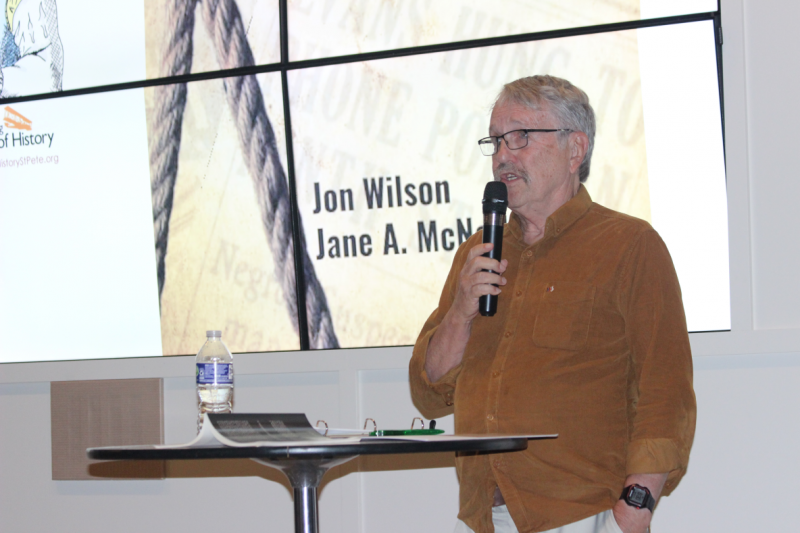

Author Jon Wilson discussed his latest book, ‘Days of Fear: A Lynching in St. Petersburg,’ which exposes the shocking story of a gruesome 1914 lynching in St. Pete at the St. Petersburg Museum of History.

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Journalist, author, and historian Jon Wilson discussed his latest book, “Days of Fear: A Lynching in St. Petersburg,” on Tuesday, Dec. 5, at the St. Petersburg Museum of History. The book, co-authored by Jane McNeill, tells the story of a gruesome murder in 1914 St. Pete.

Wilson, whose career in journalism spanned nearly four decades, called the 1914 lynching of John Evans perhaps the “most horrific event in St. Pete’s history.” When Frank Sherman was killed with a shotgun blast to his head, it unleashed days of brutality in the otherwise peaceful city and culminated in the death of John Evans, a Black man who was yanked from a jail cell and lynched for the crime.

In 1914, the city had a population of about 7,000 and advertised itself heavily as a serene place to live and visit. Businesses expected a profitable tourist season, and real estate was in demand. Frank and Mary Sherman lived on a plot of land on John’s Pass Road near the ACL railroad that Frank was hoping to develop into a subdivision called Wildwood Gardens, Wilson explained.

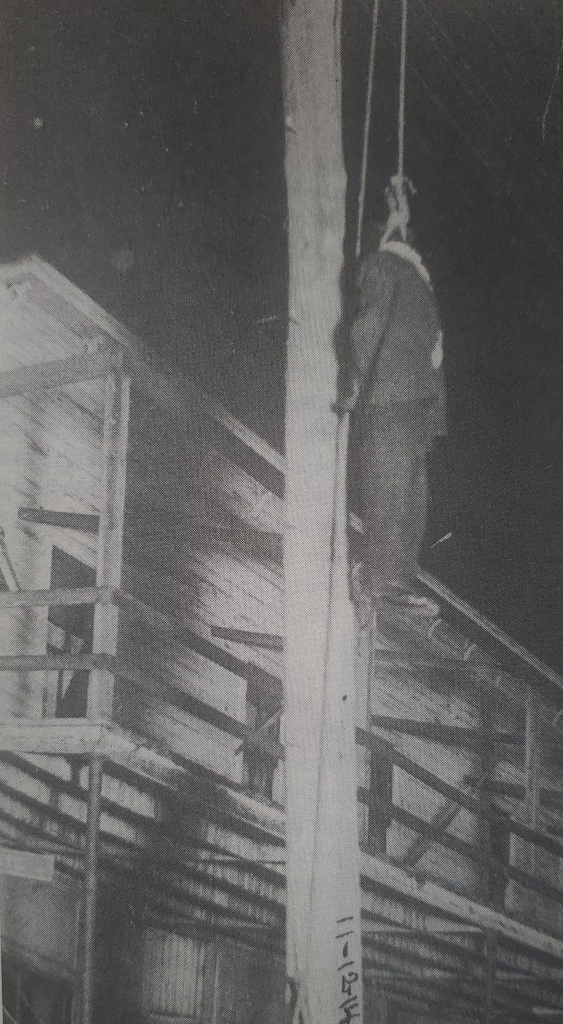

John Evans’ body dangled on Ninth Street South for nearly five hours. Mayor J. G. Bradshaw tried to stop the sale of the above postcard, saying its circulation would damage St. Pete. [St. Petersburg African American Heritage Association]

When she finally regained consciousness, she was able to slog for about half a mile through the woods to the house of a friend, Wilson said. There was no telephone in that house, so they sent someone to yet another house. As there was no phone in this house either, a young boy took the last relay and legged it to Ninth Street, where he found a telephone and called the police.

Mary Sherman then accused two Black men that she claimed had worked for her husband clearing land on John’s Pass Road. She told her story, and the “Evening Independent” newspaper published it on Nov. 11. On Mary’s word — a woman who was upset, brutalized, and beaten — the city searched for the two Black men that she had claimed assaulted her and left her for dead.

“Obviously, the news outraged a lot of white residents in town and terrified Black people,” Wilson said.

Bands of vigilante white men jumped into the buggies and automobiles and began scouring the county in search of these perceived culprits. They found John Evans, one of the men that Mary Sherman had accused, who was making no attempt to hide. The posse then took Evans to Mary at the hospital where she was being treated, but she could not identify him as one of her attackers, Wilson said. They reluctantly let Evans go.

Supposedly, new evidence was then found.

“They got John Evans again; they put him back in jail,” Wilson explained. “This was after they tortured him. They tried to hang him on the spot.”

When Evans did not confess, the authorities took him back to jail. On the night of Nov. 12, a white mob broke into the jail, threw a noose around Evans’ neck, and marched him out to Second Avenue South. Members of the mob discussed setting him on fire, Wilson said, “but they finally decided that would be inconvenient, and there was a nice telephone pole right there.” As they secured the rope and began to hoist Evans up, he was terrified and wrapped his legs around the pole.

“And just then, a car drove by,” Wilson stated. “A woman was in it and fired a shotgun into his body. A lot of the people in the crowd had their own guns, and that shotgun blast started a fusillade of fire, shot after shot.”

The shooting then stopped as suddenly as it had begun, and people started to walk away from the gruesome scene, “melting into the night,” Wilson said. Evans remained there until about three in the morning, when the police finally cut him down. This was hardly an isolated incident, as in 1914 alone, there were 55 lynchings around the country, and 51 were of Black men.

The Shermans’ lawyer, William Walsh, came to town from Camden, N.J., to settle Frank Sherman’s estate and spoke to the “Camden Courier” newspaper. That paper reported that Evans had been tried and found guilty during a secret committee meeting “composed of 15 of St. Petersburg’s wealthiest citizens,” Wilson said.

“That made a certain kind of sense, too, because remember, tourist season was coming, expected to be a good one, and St. Pete, the business establishment, did not want a supposed killer running loose or maybe going to break out of jail. Or, for that matter, a lot of armed and angry men going around the city. What they wanted was closure.”

On Feb. 23, 2021, the Community Remembrance Project Coalition and the Equal Justice Initiative unveiled the John Evans Lynching Memorial on Second Avenue and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Street.

Lula Grant, a maid alive in 1914, told Wilson in the early 1980s: “We weren’t considered in any way. We were just Black people [and] they were white people. That’s all.”

A few weeks before his murder, Frank Sherman had sold 16 lots of his Wildwood Gardens subdivision to the lawyer Willam Walsh for $3,000 — the equivalent of about $92,000 today, Wilson noted.

“I don’t know if that meant anything, but it was enough to raise a few eyebrows about the timing and who really may have been responsible for the lynching,” he said.

Wilson offered glimpses into the nomadic Shermans’ lives, who ultimately settled in St. Pete, by exhibiting photographs and old letters they had written. Frank Sherman had appealed to the president to become a government agent, and Mary had specialized in photographing children.

Evans was from Ocala and worked in the phosphate mines, which closed around 1900. Picking up odd jobs wherever he could, Evans met Frank Sherman when Sherman was on his way to St. Pete from Jacksonville, where he had purchased a new automobile. Wilson said that Sherman wanted to hire Evans as a chauffeur and do some work around Wildwood Gardens.

Ebenezer Tobin, the second man implicated in Sherman’s murder, was hanged legally in St. Pete on Oct. 22, 1915. It was Pinellas County’s first and only legal hanging. Newspapers estimated that about 2,000 people came to watch the execution, Wilson noted, which had a circus atmosphere. Sheriff Marvel Whitehurst — who initially hid Tobin and took him to jail to save him from being lynched along with Evans the year before — sold tickets at the 1915 lynching.

“A year earlier, a jury had taken 15 minutes to convict Tobin based solely on Mary Sherman’s testimony,” Wilson pointed out, adding that she moved to New Jersey afterward and did not return to St. Pete. She died at 90 in a state mental hospital.

The murder was never solved, Wilson said, and through his various travels and business dealings, it is very possible Frank Sherman acquired some enemies. For example, in St. Joseph, Mo., he testified in a trial that helped send two men to prison.

“Maybe they got out,” Wilson said. “Now, if he was a government agent, who knows what circles he had contact with.”

Wilson also speculated that Mary Sherman might have been a suspect, as her husband moved her all over the country, and her own career was put on hold in favor of his. And if Frank Sherman did not share any of the $3,000 windfall from the plot sale with Mary, Wilson speculated, “that could have been the last straw. So, it’s still an open question.”

The lynching of Evans set the tone in St. Pete for racism “up until perhaps right now,” Wilson said. “It was something that wasn’t discussed very much among families, Black or white, but people have told me they always knew about it.”

Today, there is a marker near the spot where Evans was lynched over a century ago, memorializing him and Tobin.

You can pick up a copy of “Days of Fear” at Tombolo Books, 2153 First Ave. S, St. Petersburg, or visit Amazon.com.