BY RAVEN JOY SHONEL, Staff Writer

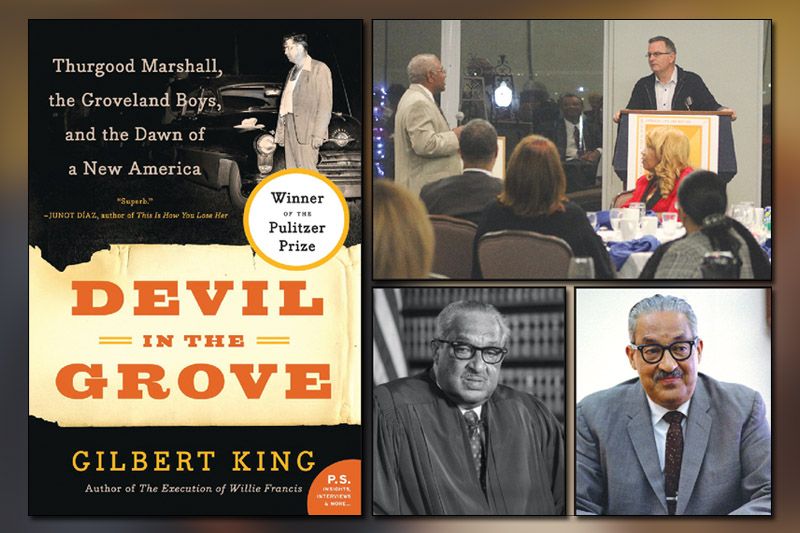

ST. PETERSBURG – The St. Petersburg chapter of The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) held their annual Black History Month celebration with Pulitzer Prize winner Gilbert King as keynote speaker.

The St. Pete Yacht Club was packed Fri., Feb. 12 all in anticipation of hearing King’s breathtaking account of Thurgood Marshall’s defense of four young black men in Lake County, Fla., who were falsely accused in 1949 of raping a white woman.

ASALH is dedicated to bringing to the entire world the history of African Americans and other members of the African diaspora. Chapter President Jacqueline Hubbard said that Marshall is one of the most positive figures of the past and feels he changed the arch of history in the United States.

University of South Florida Professor Ray Arsenault introduced King saying that “Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America” is one of the best works of creative nonfiction written in the United States in the last quarter century, which is high praise indeed since Arsenault’s book “Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice” is recognized as the definitive work on the Freedom Rider Movement.

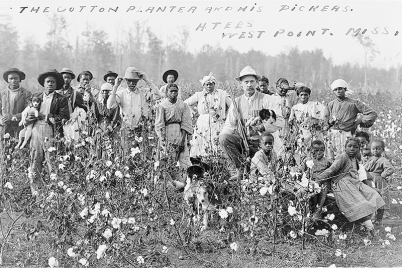

Before telling the story of the events that happened almost 70 years ago in the small town of Groveland in Lake County, not too far from Orlando, he put into context the iconic photographs of the Jim Crow South with its separate water fountains, its separate entrances and the Jim Crow balconies in the movie theaters and courtrooms.

“I think these images whitewash history in a certain way,” King said, stating that the photos depict this era as being “inconvenient” to African Americans. He said the two words that best describe the Jim Crow South are “brutality and terrorism.”

This is something Marshall lived during his time as a lawyer defending African Americans in the South. For instance, in 1946 he was working on a case in Columbia, Tenn., where 24 black men were on trial for attempted murder of policemen.

These policemen also doubled as Klansmen and were firing indiscriminately into houses and businesses in the black section of town. A group of African American, who had just come back from serving their country in World War II, fired back. Marshall got involved in this case and against the odds all of the men were acquitted in a Southern court.

On his way out of town after the verdict, he was pulled over by the police, yanked out of his car, thrown into a police car and was driven down to the river. King said the future Supreme Court Justice thought he was going to be lynched, but the reporters and lawyers who were in the car he was originally traveling in circled around and followed them. The police thought there were far too many witnesses, so they tried to arrest him for drunk driving instead.

“We think about the Black Lives Matter movement now but you can look back to Marshall,” said King. “He was really on the forefront of this, and by himself he would go down to explosive and dangerous places.”

“Devil in the Grove” gives the account of a young white couple, Willie and Norma Padgett, who told the police they were on their way home from a dance when their car stalled on a lonely road. The two said that Sam Shepherd, Walter Irvin, Ernest Thomas and Charles Greenlee pretended to help them with the car, attacked and left him on the side of the road while driving off with 17-year-old Norma. She then told the police she was raped by each of the four young men who came to be known as the “Groveland Boys.”

By the next morning, King said, the Ku Klux Klan had rolled in by the hundreds and began burning down the black section of Groveland. The violence got so bad that Life magazine decided to send a photographer down. Although the story was never published, there are some 90 photos of the event.

The violence got so bad that the National Guard was sent down to keep the peace for a week. King said the African Americans in Lake County had an unlikely ally in the citrus barons of the area. They didn’t want to face financial ruin, so to keep the cheap labor from fleeing they sent in protection.

Three of the four accused were taken to jail and Ernest Thomas fled into the swamps. Sheriff Willis McCall put together a posse of about 1,000 men, chased him down and riddled his body with bullets. King said that one newspaper reported that 400 slugs were taken from Thomas’ body.

King said Marshall was told by advisors that there was no way a black lawyer could stand up in court and question the word of a white woman. There was no surer way to turn the jurors against him than to suggest that a white woman was lying. Taking their advice, Marshall got a white lawyer involved in the case.

The defense team didn’t question if she was raped, but that she had identified the wrong people. King said they couldn’t even call in the basic facts of her testimony because it would have been too explosive.

The prosecutor tried to coax a witness into saying that when Norma came into the café where he was working with a torn dress and hysterically crying. The young man decided to tell the truth that she came in and sat down calmly for about 15 minutes never mentioning anything about a rape or abduction.

None of that mattered, the Groveland Boys were found guilty. Irvin and Shepherd were sentenced to the electric chair and 16-year-old Greenlee, because of his age, was given mercy with life on a chain gang. King stated that Marshall said that’s how you know the jury thought your man was innocent, he only got life.

Marshall knew he was going to lose the case, so he was ready to appeal.

“They might get run out of town in these Southern courts, but once Marshall could get them in front of the U.S. Supreme Court, he felt that it would be a level playing field,” said King.

The Supreme Court overturned Irvin and Shepherd’s appeal (Greenlee did not appeal), and on the eve of the retrial, McCall personally went up to the Florida State Prison in Raiford to pick the two up. On the way back he pretended to have a flat tire and turned down a dirt road.

Spraying the two with bullets, Sheppard was killed instantly and Irvin miraculously survived and pretended to be dead. He heard McCall on the radio saying that he had got them.

McCall claimed that he let the prisoners out to use the bathroom and they overpowered him so he had to shoot them. Once his deputy arrived on the scene, he noticed that Irvin was still breathing. He proceeded to shoot him in the neck, and bullet passed through and lodged in the ground.

When the ambulance arrived to take McCall to the hospital, it was then noticed that Irvin was still alive. He was transported to the hospital and once he regained consciousness, he told a different story.

Irvin told Marshall, the FBI, other lawyers, the police and a court stenographer that McCall made them get out of the car and opened fire on them. Since five of the bullets had been recovered, the FBI went back to the scene to search for number six. They found it under a pool of Irvin’s blood proving that he was shot at close range.

“This is about as close as you can get to a dash cam or a cellphone. This is forensic evidence of murder and attempted murder,” said King.

Despite the FBI’s damning report, Irvin was given three weeks to heal and put back on trial. He was found guilty again after turning down a deal that would give him life in prison if he would just admit to raping the white woman.

If you would like to know what happened next, you will have to pick up the book. King wanted the audience to know that Marshall recognized the limits of the law. He knew that there was only so much that could be accomplished in a courtroom, and at the end of the case he started to use his influence outside of the courts.

He organized the citrus boycott, and got clergymen to hire private investigators to go down to Groveland and got everyone in the community to sign a petition abolishing capital punishment. They even got Norma and her family to sign.

These were just a few acts Marshall did outside of the courtroom to effected public opinion.

Marshall argued cases in the South in antebellum courtrooms with the Jim Crow balconies knowing that he would lose. However, what was important was that the hundreds of people in the balconies would see an African American in a suit arguing the law, King said.

“It gave them a glimpse of what is possible and it gave them hope. Even though he knew he would lose, he was inspiring people across the county,” stated King, who feels that this is Marshall’s legacy.