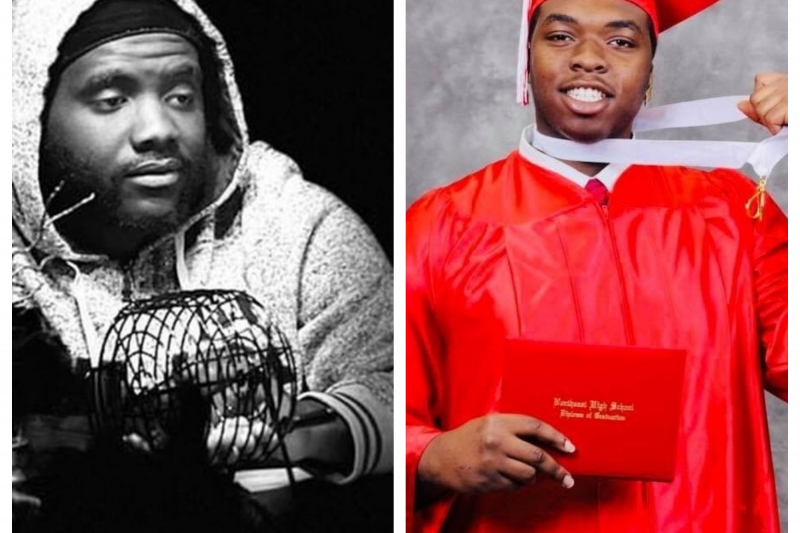

From left, native sons Dallis Patrick Ryan Wolfe, and Marquis Scott were killed by senseless gun violence.

BY GABRIELLE SETTLES, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Last November, a string of shootings left seven people injured and three dead, bringing the total number of deaths last year to nine people. St. Pete is one of many cities across the country that’s trying to combat the issue of gun violence.

Data shows that the number of those killed is down from years prior — guns killed 13 people in 2019 and 15 were killed in 2018, but many would agree that any number of deaths are still far too many. While the statistics give the facts, they don’t reveal the aftermath of trauma left behind when these crimes are committed.

City Councilmembers Deborah Figgs-Sanders and Lisa Wheeler-Bowman sat down to talk about this in an open virtual meeting called End The Violence: There is No Single Victim. They met with community leaders and family members of victims as a part of their greater initiative: Enough is Enough.

The meeting’s topic was to reveal how an act of gun violence can send waves of effects through the families and the community that surrounds them.

“I wanted to have this conversation so that we hear voices to understand that the violence in our community is not a single-victim issue,” Figgs-Sanders related in the meeting. “It doesn’t just impact that one single person; it doesn’t impact that one single-family … it impacts all of us.”

Wheeler-Bowman, whose own son died in a shooting incident more than 12 years ago, told the audience she knows firsthand about these experiences.

“I am glad to be a part of this [conversation],” Wheeler-Bowman said. “I share in the grief, the pain, the healing that I know that will come out of having conversations like this.”

The councilmembers turned the conversation over to Rev. Kenny Irby of Bethel AME Church to open the meeting in prayer and to the founder and director of The Well for Life, LLC, Dr. LaDonna Butler, who moderated the event’s panelists.

Butler started the conversation by first introducing the family of Dallis Patrick Ryan Wolfe, a native of St. Pete and senior studying psychology at Alabama A&M University. He would have graduated this May, and he planned to pursue studies in behavioral neuroscience to work with children. Sadly, Dallis’ life was taken away by gunfire before accomplishing that goal.

Wolfe’s family has owned Starling’s School and Daycare Center in St. Petersburg for nearly 50 years, and his aunt Jennifer Howard Black said that he was the epitome of what they teach their students daily.

“Proverbs 22: 6 says, ‘Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it’. We say this every day at Starling School, and I’ve been there over 30 years myself. We saw Dallis doing just that,” Black said.

Wolfe lived in an off-campus apartment during his senior year, and one of his roommates let someone stay with them. However, that person overextended their welcome.

“Dallis had been asking them since September to leave,” Black stated. “He did contact the office apartment community complex about it.”

Things escalated earlier in January when the young man confronted Wolfe and shot him. He died on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

“It was ironic that Dallis died on Martin Luther King Day because Dallis was nonviolent just like Dr. King,” Black averred. “And this young man took his life because Dallis was always taught to do what’s right.”

Black said that the family has been grappling with their loss and are seeking justice.

“We now too know just how senseless a murder can affect the entire family [and] the entire community,” Black said. “We are soliciting support as we continue to fight so this won’t happen to another college student again, never.”

Fellow panelists Maress and Marjorie Scott have also experienced this same pain. They lost their youngest of five sons, Marquis Scott, aged 20, in a shooting two years ago.

Marress Scott said the hopelessness they felt was like when Africans and African Americans were snatched away from their families during slavery.

“That hopelessness was there; [it felt] hopeless and hapless that you couldn’t do anything about it,” he described.

Even amid tragedy, the Scotts shared how they have taken the steps of healing.

“What we’ve leaned on was our faith. Our hope and our trust in God led us on a slow but steady path of healing, and what we had was an opportunity to come in close as a family,” Marress Scott explained. “We didn’t want the pain of our loss to create a bitterness of unforgiveness that manifested itself in the way we deal with each other, as well as the way we forgive others and how we deal with people in the community.”

Marjorie Scott shared that connecting with others who have experienced the same tragedy has been a huge help. A friend introduced her to a group called Circle of Mothers, and she joined a few months after Marquis Scott died.

“It helped me a lot because I was with a group of people who knew what I was going through. And they were able to let me know what I was feeling was normal,” Scott said. “They were able to provide answers to a lot of the questions that helped me go through the whole thing of him being murdered [and] the investigation.”

The Scotts said that every month, they have a celebration to remember Marquis Scott’s life in a positive way. They also have cookout gatherings — under COVID protocols, Maress Scott added — to meet with his friends.

“We were able to be a surrogate healing place for those kids. We were able to discuss the process of grief so that people could recognize the stages of grief because people didn’t understand what they were going through,” Maress Scott shared. “I believe that process helped with the healing of not just ourselves but those young men and young women that were connected to our son as well.”

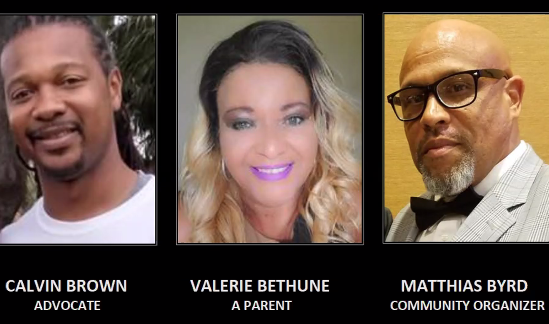

Other panelists on the virtual meeting were also affected by gun violence but in another way. Valerie Bethune’s youngest son is serving a life sentence because of homicide. Calvin Brown and Matthias Byrd shared how they turned their lives completely around after participating in gun violence.

Bethune shared that the trauma of her son’s incarceration still affects her and her family. He hasn’t passed away, but it is a loss of life in a different sense, Bethune said. When the judge told her that her son had a life sentence, she said she felt her son die.

“The thing that I want everybody to know, my son is alive, yes. But he’s in prison. He will never come home,” she said. “Whether it’s a death or incarceration, the grief is still the same. I can’t talk about my son because I still cry like it happened yesterday, and it happened 12 years ago.”

When her son went to prison, Bethune took in her grandson, who she still raises today. She also takes care of her granddaughter on weekends. Her oldest son also pitches in.

Bethune shared that this has affected her family’s mental and emotional health. She had to wait for months until a therapist could see her grandchildren, and she’s had to fight to stay strong in her emotional state. Because of this, Bethune can only see her son once every three years.

“I don’t go see my son like you would think I would because of health reasons,” Bethune said. “The doctor gave me a choice: you either go see your son or you live.”

Bethune shared that she has panic attacks followed by depression for months when she leaves the prison.

Her grandson is now 16, and understandably she’s protective over him. She hopes the community can change for their children.

“We all gotta start grabbing ahold of these kids, loving on them and guide them to something else besides guns. Because it’s not worth it, because it affects too many people,” she said.

St. Petersburg native Matthias Byrd knows this all too well. He’s now a husband and father of what he describes as a beautiful family. But his past was very different.

“From the age of 15 to 29, I lived by the gun. I believed in the power of a gun,” Byrd said. “I just want to bring to the light that there are victims on both sides. Those young men that are willing to pick up a gun and use it against someone for minute reasons are also a victim of a bigger problem.”

Byrd said he picked up a gun because he was scared for his life. The gun “was the man of the house.”

“Anytime that I needed comfort and I needed to feel protected, I went to my gun. I was never a bad person. I was hopeless,” Byrd said.

The event that changed his life happened when he survived a shooting. With two gunshots to the chest — one of the bullets still too close to his spine to be removed — he laid on the floor, not sure if he would ever get up again.

“It wasn’t until that moment until I thought my life was over when I really recognized how much value my life has and how important I was to at least three or four people,” Byrd recalled.

Thinking about the lives of loved ones is what changed fellow panelist Calvin Brown’s life, too. He spent his adolescence “throwing rocks at the jail” and was arrested in 2007. But it wasn’t until his daughter’s birth that Brown began to work at changing his life. It wasn’t easy to do so as a convicted felon in St. Petersburg, he said.

But a tragedy in 2012 was a pivotal moment. Byrd’s two nephews, Zander and Zayden Brown, ages 7 and 5, were killed by their mother suffering from extreme depression.

After that incident, Brown became an advocate for the community and a counselor at The Well for Life, where he works with Dr. Butler. He said that to change a situation and help others, it must be approached with forgiveness, healing, and love.

Brown echoed Bethune’s sentiments — our youth must be given different options besides going to the gun and hanging out in dangerous areas.

“The reason these kids are doing a lot of the things they’re doing and [there are] a lot of these senseless deaths is because they don’t have any outlets.” Brown asserted. “They don’t have ways for their voices to be heard or ways to express themselves, so as a community, we have to give them some way to express themselves always and be there to listen to them.”

The panel collectively shared ways community reform can occur, such as listening first before pointing fingers and preaching to the youth, and maintaining a clean community. When people see a clean environment, it gives them a sense of pride in their area.

The panel also asked if counseling services could be made far more accessible for children. Figgs-Sanders and Wheeler-Bowman promised to make sure as elected officials they would not only listen to solutions but follow through on them and remain accountable.

Near the end of the discussion, Zoom bombers tried to overtake the discussion with racist and derogatory slurs. While shocking, it only lasted for a couple of minutes until they were removed.

The bombers did not end up having the final word in a meeting that was meant for healing, and the panel remained on course.

“There will always be distractions to true healing,” Butler said. “We will continue to advocate for policies that keep us safe and affirmed in our full dignity as a people.”

Another collaborative lab is scheduled for Feb. 16, Figgs-Sanders said, so the community will know that they are being heard and actions will be taken.