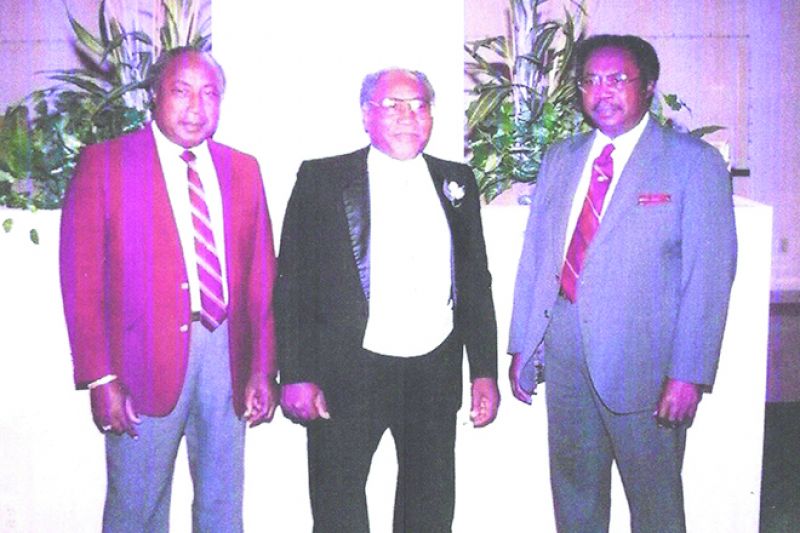

The patriarch of the Welch family, Flagmon Welch, had a powerful work ethic. Pictured are his sons, David, Clarence, and Johnny Welch.

BY JON WILSON | Columnist

ST. PETERSBURG — A powerful work ethic guided St. Petersburg’s African-American pioneers, and Flagmon Welch was one who personified the value. That work ethic has been passed through generations.

Welch, who came to St. Petersburg in 1917, was the patriarch of a family that includes sons David Welch, an accountant and former city council member; Clarence Welch, a religious leader at Prayer Tower Church of God in Christ; and Johnny Welch, also an accountant. Grandson Ken Welch is a current Pinellas County Commissioner.

Flagmon Welch came from Alachua County, and when he got to St. Petersburg, he took any work he could get. That included carrying water for the workers building Gandy Bridge in 1922. The job paid $5 a week.

He and a cousin, Herman Welch, soon started a landscaping business. They collected cow manure from a dairy that eventually became the site of Sixteenth Street Junior High (now John Hopkins Middle School). They mixed the manure with dirt and spread it into new lawns in swanky subdivisions such as Snell Isle.

In 1925, Flagmon Welch opened his signature business: the Welch Woodyard on 16th Street South and Dixie Avenue. Traveler’s Rest Church built a sanctuary on the site, so Welch moved the wood yard to 16th Street and Fifth Avenue South. There, it became a landmark business for half a century.

Open seven days a week from dawn to past dark, the yard furnished wood for heat and cooking to families throughout St. Petersburg, black and white alike. Welch also supplied rich, black dirt, which the entrepreneur collected from Goose Pond, a swampy area in central St. Petersburg about a mile northwest of the wood yard. Goose Pond eventually became the site of Central Plaza, the main post office, and many other businesses.

“On cool days, we’d have cars lined up,” said David Welch, one of Flagmon’s sons. Two others, Clarence and Johnny, also worked in the yard for hours on end.

“From the time we could tote wood, we were working,” said Clarence Welch.

His father got the wood from around the countryside – forested spots remaining in Pinellas County and other locations that required travel. Father and sons sometimes took the Bee Line Ferry across Tampa Bay to Manatee County before the Sunshine Skyway was completed in 1954.

They gathered oak and pine and brought them back on the boat. It sold in 12-inch chunks for pot-bellied stoves and 24 or 48-inch pieces for fireplaces. A customer could come with a wheelbarrow and fill it up for $2.

Able to read the grain of the wood, Flagmon Welch swung an ax like a lumberjack.

“He could break a piece of wood with one whack,” said Clarence Welch. Flagmon Welch was a deacon for 68 years. He taught his children responsibility, spirituality, honesty, and unity.

His son David Welch said: “I remember he was always saying, ‘I want to make this a better world for my kids, my grandkids and my great-grandkids.’ That’s all he lived for – his kids. He didn’t want them to go through the same things he had gone through.”