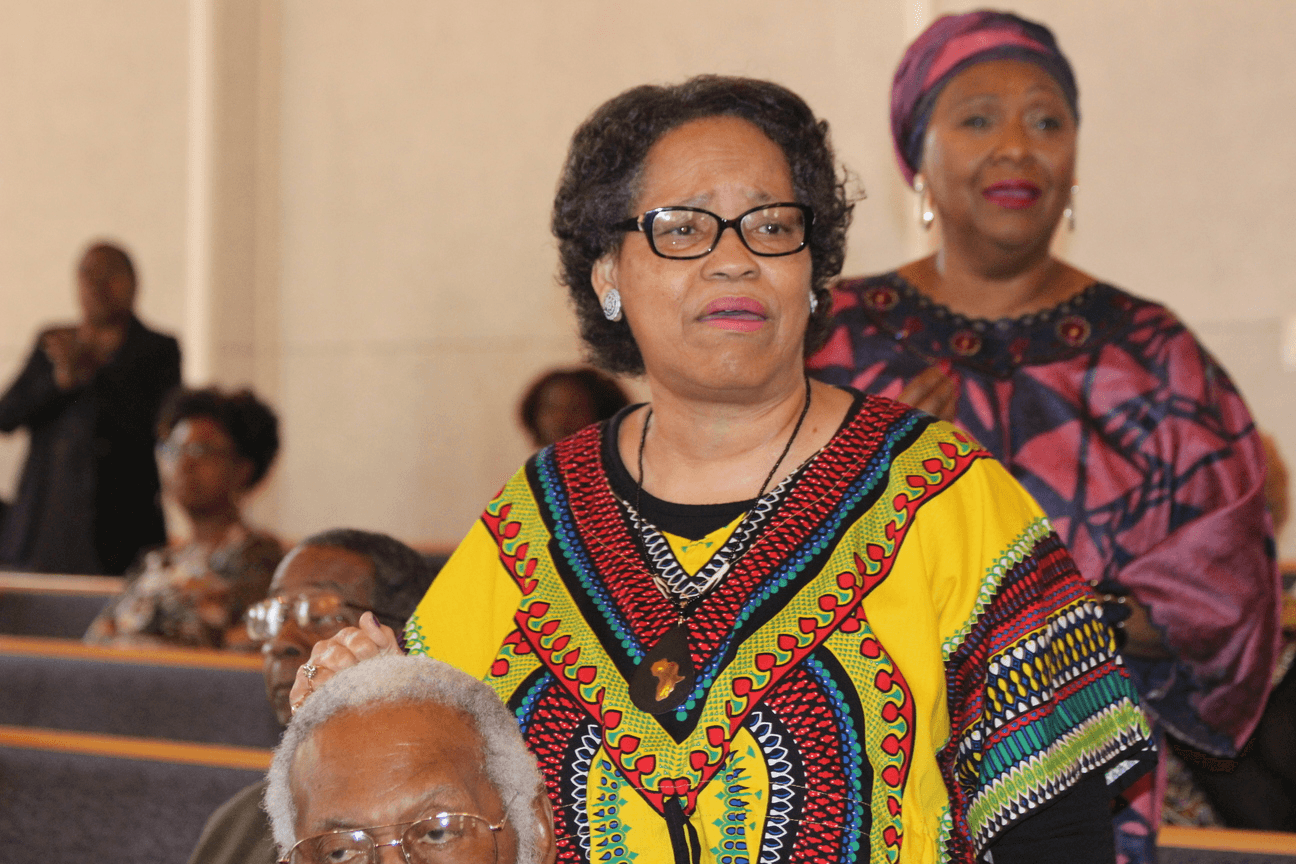

Dr. Yohuru William headlined Greater Mt. Zion AME Church’s Black History Month celebration on Sunday, Feb. 25.

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – Greater Mt. Zion AME Church is known for bringing the country’s brightest thinkers to St. Pete annually. Rev. Clarence Williams and the Black History Committee, chaired by Orlando Pizana, spare no expense when it comes to educating Black minds.

Dr. Yohuru Williams, the Distinguished University Chair and Professor of History and Founding Director of the Racial Justice Initiative at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn., headlined this Black History Worship Celebration on Sunday, Feb. 25.

Attorney Deveron Gibbons presided over the program while Miss Emerson Jackson read Isaiah 46:9, which anchored the morning’s celebration: “Remember your history, your long and rich history…”

In introducing Dr. Williams, Pastor Williams told everyone to get ready and “buckle up, as this is what Black history is all about!”

Williams said, “Sometimes when we talk about African-American history, we get so fixated in the past about what great people have done, we forget there’s an obligation and a duty in the present to act.”

“Sometimes we talk about history as if it’s just secular, but let’s be clear…this is all spiritual warfare,” he said.

Today, some get very uncomfortable when people say, “Black lives matter,” but Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said the same thing over 60 years ago in his “I Have a Dream” speech; he just didn’t use the same language, Williams said.

As the nation faced mounting criticism from countries like the Soviet Union about the “Negro problem” with its segregation and Jim Crow laws, President John F. Kennedy delivered an address on television in 1963, calling civil rights a “moral issue…as old as the scriptures,” and noting that “the heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated.”

“Last time I checked, that’s scriptural!” Williams pointed out. “Kennedy had to go to the Bible to get the American people to recognize what you’re doing is immoral and unconscionable.”

Opponents of Kennedy’s view also claimed spiritual truth, “that God never ordained Black and white to spend time in the same place,” Williams said, specifically people like Gov. George Wallace, a fierce segregationist who went so far as to stand in the doorway at the University of Alabama to block two Black students from registering.

Attempting to block integration at the University of Alabama, Governor George Wallace stands defiantly at the door while being confronted by Deputy U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach.

Williams referenced Exodus, where God decrees that his followers shall have no other Gods before Him, yet throughout our history, “whiteness is kind of idolatry,” he said, as whites have always placed themselves above the African Americans and the indigenous populations.

“If you think you’re so great that I can’t be buried next to you, then you obviously don’t put the Maker first; you put color first!” Williams averred.

Attempts in the late 19th century to assimilate the indigenous population into white society, Williams pointed out, employed the same methods that were used on Black people: segregation, degradation, and erasure.

America has never adequately dealt with its history of slavery, and these days, fewer people are willing to even talk about it, he said, because they don’t want their children to “be exposed to the horror” and the psychological damage it may inflict on them. But what about the damage the young Black children have experienced firsthand, he asked.

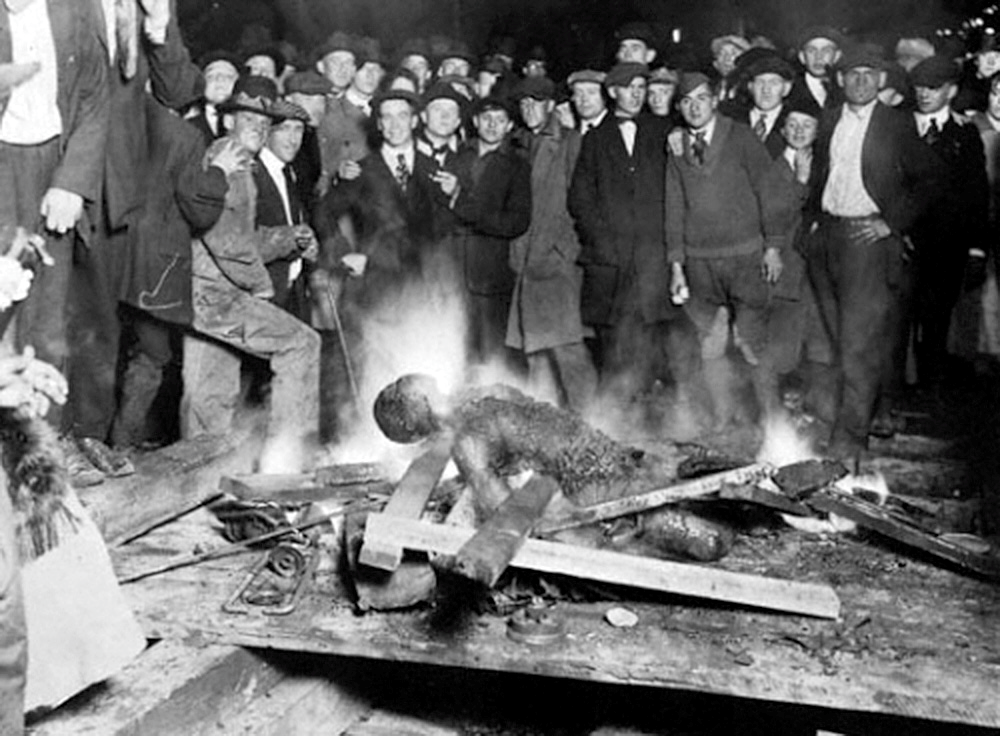

A group of white men pose for a 1919 photograph as they stand over the body of the Black lynching victim Will Brown before they decide to mutilate and burn it during the Omaha race riot of 1919 in Omaha, Neb. Photographs and postcards of lynchings were popular souvenirs in the U.S.

He remarked that when General Order No. 3 was formally announced on June 19, 1865, a day that came to be celebrated as Juneteenth, it did not end slavery. The 13th Amendment did that, as up until then, there was no guarantee that the country wouldn’t go back to slavery. While this Order announced the enslaved now had their freedom and could work for wages as free men, it came with caveats.

“This is a proclamation; it’s not a 10-page document that says your wages are to be X, and you’re supposed to get this healthcare, and you’re supposed to get this Sunday off so you can worship your God!” he said, adding that it kept the formerly enslaved in a subservient position.

Furthermore, Order No. 3 said, “[T]he freed are advised to remain at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.” The reason Black people were running away to military posts was to present themselves for service, Williams said.

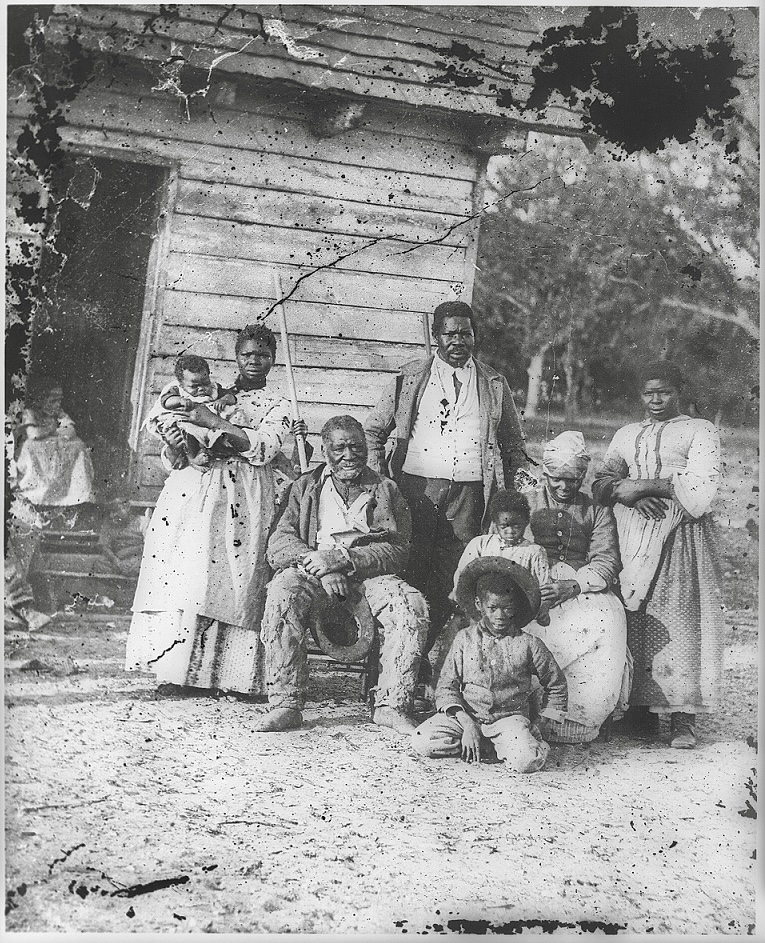

Four generations of a formerly enslaved family on J. J. Smith’s confiscated plantation at Beaufort, S.C. in 1862.

“Now you have Juneteenth with the narrative of us that we were lazy, walking off the plantation and expecting that we were going to be idle at the military post!” Williams said, adding that those formerly enslaved people had no desire to stay at those very plantations where they had been in servitude.

African Americans have been getting empty promises for years, Willams said, pointing out the various acts that “had no teeth,” like the Civil Rights Acts of 1875, 1866, and 1957.

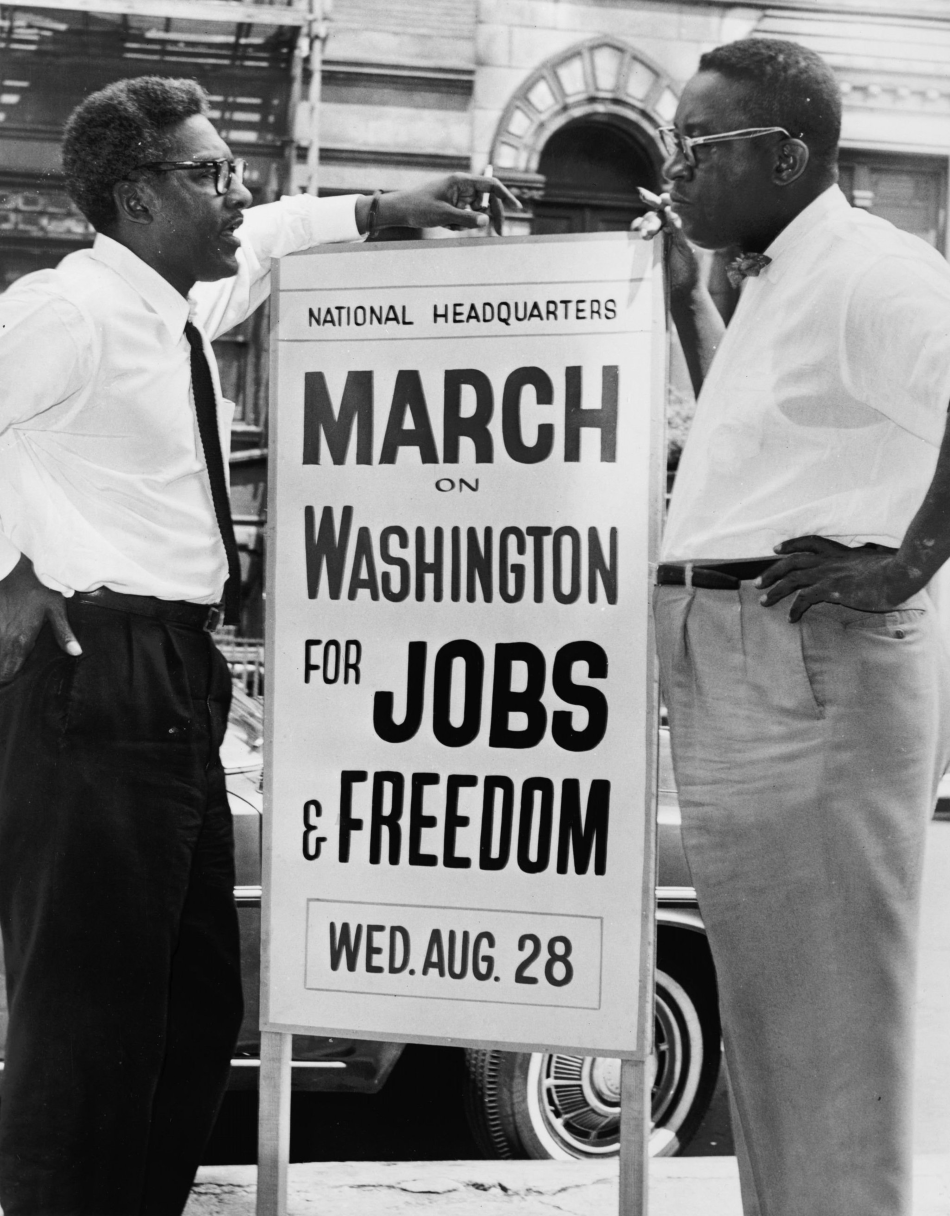

Nearly a century later, Dr. King began his “I Have a Dream” speech by saying that America had given Black people a “bad check,” exemplifying the empty promises and ongoing inequality. At the March on Washington, some carried placards and signs that read: “We Demand and End to Police Brutality Now!”

History doesn’t repeat itself; it echoes, Williams said, drawing a line from those signs over 60 years ago to the Black Lives Matter Movement today and the police beatings and killings of African Americans. Other placards from the march demanded decent housing and decent jobs.

Bayard Rustin (left) and Cleveland Robinson (right), the March on Washington organizers, on Aug. 7, 1963.

“The problem is we’re getting these cycles where we have unfinished revolutions,” he said. “We need a comprehensive Civil Rights Act that deals with housing, education, access to places of public — that puts teeth back into what it means to be an American citizen!”

Williams ended by saying, “Black history is American History, but Black history without faith is just like faith without works. And what we need right now is works.”

Dr. Yohuru Williams is the author, editor, and or co-author of several books, including “Call Him Jack: The Story of Jackie Robinson, Black Freedom Fighter,” “After Life: A Collective History of Loss and Redemption in Pandemic America” and “Rethinking the Black Freedom Movement.” He is also a regular contributor on the History Channel, ABC, NBC, MSNBC, NPR and others.