Author and scholar Dr. Khalil Gibran Muhammad, an influential authority on racial justice in America, discussed the role race has played in shaping today’s economic inequities at the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg on Feb. 1, kicking off Black History Month.

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Author and scholar Dr. Khalil Gibran Muhammad, an influential authority on racial justice in America, kicked off Black History Month at the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg on Feb. 1. As part of the Foundation’s “Speakers Who Inspire” series, Dr. Muhammad discussed the role race has played in shaping the economic inequities of today.

Muhammad is the Ford Foundation Professor of History, Race and Public Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School and author of “The Condemnation of Blackness.” His work has been featured in the landmark New York Times’ “1619 Project” and Ava DuVernay’s Oscar-nominated Netflix documentary “13th.”

Introducing Muhammad, President and CEO of the Foundation, Dr. Kanika Tomalin, told the audience that they would “leave here tonight a more connected community and a more historically literate people” and praised him as a scribe who writes about racial histories and the inequities that plague our society.

In these divided times, he noted, merely talking about race or gender in about two dozen states in the country has been made illegal because these are so-called “divisive concepts” that make people feel uncomfortable. Voter suppression laws have also sprung up, solving for election integrity, though there is little evidence of election fraud.

He touched upon the recent banning of books from school libraries, noting that “children [may] get the bright idea that everybody should vote, children get the bright idea that inherited wealth creates inequalities, that’s not a function of one’s personal ambitions or personal irresponsibility. Some people are simply born in neighborhoods that have a lot more, including healthy air to breathe, healthier and more affordable food to eat.”

“When books are written about such things and give people the fanciful notion that they might have something to say about this as voters, then we understand the broader context in which schoolbook bans have erupted around the country,” he said.

After a Federal court ordered the desegregation of schools, U.S. Marshals had to escort young Ruby Bridges to school.

The absurdity of these attacks can best be exemplified by certain school districts banning a book about Ruby Bridges, the first African-American child to attend a white-only school in Louisiana at the onset of desegregation, Muhammad said, because of the fierce opposition by whites at the time.

The story of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the March on Washington has also been banned because the story included instances of the Birmingham, Ala., campaign, where small children and teens were subjected to firehoses by firemen — stories such as these are banned to spare white children and their parents’ discomfort when faced with the brutal truth of history, which itself is not in question.

“We’re really fighting over the power to have an educated and informed populace who can genuinely defend democracy,” he said.

As this country becomes more Black and Brown, some see this as a fundamental threat. It’s a form of denialism, he said. We talk of the need to return to colorblindness because some believe talking about race is racism. Colorblindness is a form of denial about how systemic racism shapes individual life outcomes.

Gender blindness is a form of denial that girls, women and gender nonconforming individuals are now impacted by systems, norms and customs designed to privilege men. Climate blindness is a form of denial that carbon emissions are not warming the planet.

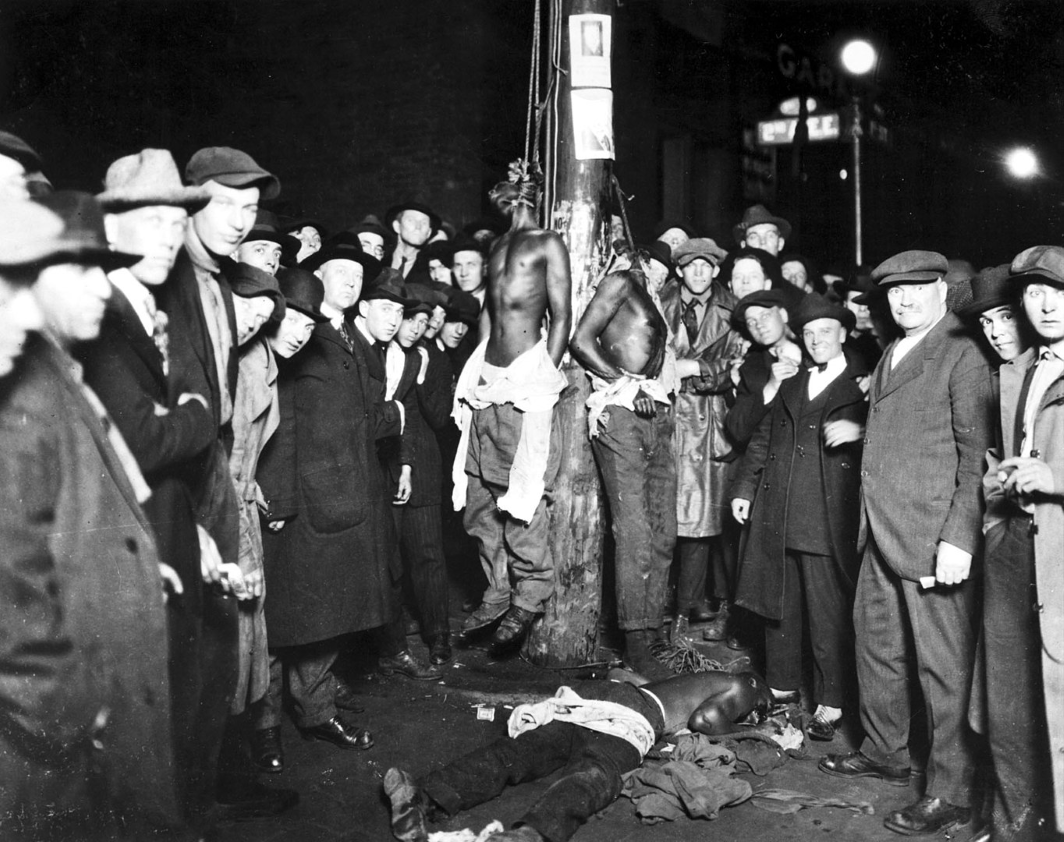

The Arthur family arrived at the Chicago Polk Street Depot on Aug. 30, 1920, two months after their two sons were lynched in Paris, Texas.

In the waning days of the Civil Rights Movement, Gallup polls found that after the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a majority of white Americans thought that the movement had gone too far, Muhammad explained. This viewpoint isn’t new. During the Great Migrations, when many African Americans fled the rural South for urban centers beginning in the 1910s, many urban leagues sprang up. They advised the incoming Black migrants on how to dress in public to look acceptable and how to hold on to a job by being efficient, industrious, and sober. One league in Detroit even advised them not to “sit in front of your house or around Belle Isle [in Detroit] or public places with your shoes off.”

“Most of these early decades were dedicated not to fighting the actual legal machinery of segregation and the absolute terror of mob violence that sometimes resulted in 10,000 people watching a person hanging from a tree, or burning in a fire pit and then their body parts cut off and sold as souvenirs and postcards sent all over the country — all of this which happened,” he said. “Much of what the focus of attention was on how to make Black people be better people.”

On June 15, 1920, three African-American circus workers, Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie, suspects in an assault case, were taken from the jail and lynched by a white mob of thousands in Duluth, Minn.

For the most part, Black people were hard workers who followed the rules. Yet some of the most successful — who managed to own land and cultivate crops or opened businesses to serve their segregated communities — were some of the first to be subjected to white mob violence.

“Unfortunately, this wasn’t limited to the South where Black people were essentially told: ‘Make white people feel comfortable in order for you to have a decent shot at success,'” Muhammad said.

The segregation in cities like Detroit or Chicago was never going to be solved by how well-behaved these migrants were. Fast forward to the 1980s, when images of a hyper-visible Black middle class, such as photos of successful Black bankers and businesspeople in glossy magazines, sent signals to the rest of white America that systemic racism no longer existed.

But that would be the equivalent of saying, “Because Sheryl Sandberg was a high-ranking CEO at Facebook, that there is no such thing as discrimination or bias or systemic inequality that women face in this society.” In 1985, Glen Loury, a Black conservative economist, believed that “racism isn’t the problem,” Muhammad said, “the inferiority, the dysfunction, the pathologies, the bad behavior, the bad parenting, the bad studying — that’s the problem!”

Fast forward to 2009, to a book by Black author Ellis Cose, where he maintained: “Racial issues aside, America is a blessed, magical place.”

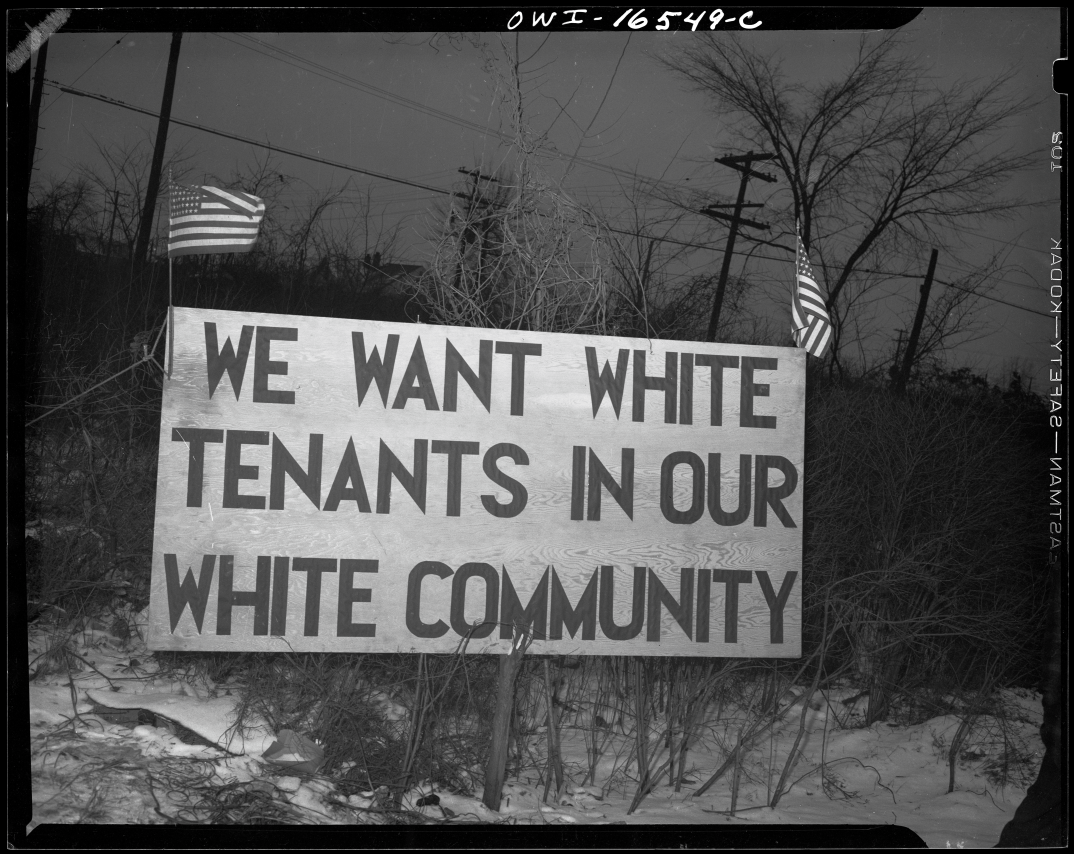

In 1942 Detroit, white tenants erected a sign to prevent Black people from moving into a housing project.

“That would be like saying, the lump in your kidney — if you don’t look at it and don’t believe it’s cancer, it’s not cancer,” Muhammad asserted. “It makes no sense.”

Another part of Cose’s book advised people to “never talk about race or gender if you can avoid it, except to declare it does not matter.”

“This form of denial is not just for white people,” Muhammad said. “It’s an American thing. And it’s deadly because it means that you can’t actually solve the problem that you face.”

Black people have endured systemic racism and economic inequality because we haven’t been solving for it, Muhammad pointed out.

“You can’t fix something that you are not willing to address,” he said.

Muhammad delved into some of the history of the slave trade and its part in the country’s economic rise in the global community. He took a veiled shot at presidential candidate Nikki Haley, who recently refused to name slavery as a catalyst for the Civil War.

“To recognize the footprint of slavery is to recognize the centrality of race and racism to American history,” he said.

Though the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, except as punishment, it left a gaping legal loophole. What the Civil War took away, he explained, the 13th Amendment put back. Consequently, the infrastructure of punishment in this country became a primary way to control the labor of Black people — until they left the South in droves.

A scene from the 1915 film, ‘Birth of a Nation’ depicts hooded Klansmen catching a Black man portrayed by white actor Walter Long in blackface.

The cultural narrative of Reconstruction was captured by “Birth of a Nation,” a film released in 1915 that depicted Blacks as “criminals, as alcoholics and ne’er-do-wells, who were corrupt and ruining the nation, and ultimately needed to be put back in their place, which of course, the Ku Klux Klan would ride to the rescue and do,” Muhammad said. “And in so many ways, that’s exactly what happened.”

In the ensuing decades, redlining was rampant — in one instance in Detroit, they built a six-foot high wall to separate the Black side of town from the white. That wall still exists to this day. The impact of redlining and the predatory lending practices toward Black people that have been going on since the 1990s and well into the 2000s go a long way to explain the wealth gap and housing gap that exists in this country.

“If we all learned this in school, we’d have a better country today,” Muhammad said. “We might now be here talking about equity; we might be talking about something else.”