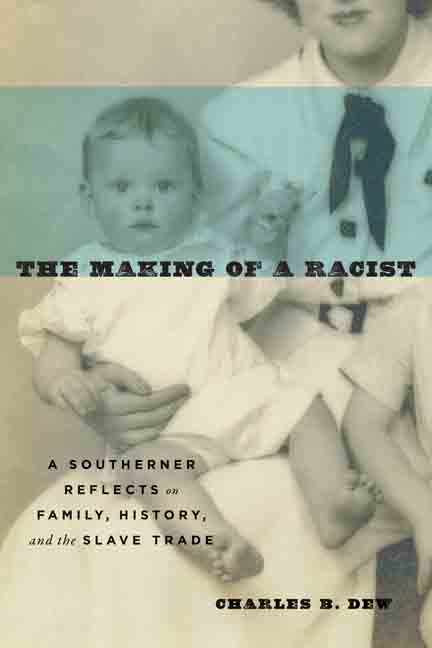

Dr. Charles Dew sat down with Gwendolyn Reese, president of the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, to discuss his 2016 memoir ‘The Making of a Racist: A Southerner Reflects on Family, History, and the Slave Trade.’

DEIRDRE O’LEARY | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Dr. Charles Dew’s 2016 memoir “The Making of a Racist: A Southerner Reflects on Family, History, and the Slave Trade” was the subject of January’s virtual “Community Conversation” sponsored by Tombolo Book and hosted by Gwendolyn Reese, president of the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg.

When Reese contacted Dew, a St. Pete native and retired professor of southern history, after reading “The Making of Racist,” he informed her that he wrote the book for white people and was surprised by the reaction to it.

When Reese contacted Dew, a St. Pete native and retired professor of southern history, after reading “The Making of Racist,” he informed her that he wrote the book for white people and was surprised by the reaction to it.

“I said, ‘You answered a question for me that has haunted me all of my life, and that is why racism is passed from generation to generation, and how it is passed,'” Reese replied.

Dew — one of the most renowned historians of the South and slavery — often used stories about growing up in Jim Crow St. Pete when teaching his Southern history classes.

“I would often use these antidotes of my own experience to make a point about how powerful racism was and how it wasn’t just a sort of redneck phenomenon [but] that it embraced the entire social, economic and cultural spectrum of the white South, and sort of drew them into this racial attitude that was pervasive and pernicious,” he averred.

When he decided to write the book, Dew used himself as a primary source and told the story from his own experience, which would be beneficial to a white audience.

He said the trigger to write the book came when a rare book library acquired a price list issued by a slave-trading firm in Richmond, Va., in 1860. This printed form had spaces for descriptions and prices. He looked at this document and felt like he had been slugged in the gut because here in his hands was the essence of the South’s cancer.

“The cancer that was planted in this society at its inception in 1619, and a cancer that just metastasized over the years until it essentially took over that society, its economy, everything about it.”

Since all of Dew’s ancestors were from the South, he wondered how they were complicit in the racism. Then he realized that he had done the same thing growing up in segregated St. Pete.

“Looking at that every day was omnipresence. It was everywhere; it was right in front of my nose, and I did not see it,” he said. “I thought to myself I was complicit in my society the same way my antebellum ancestors were complicit in theirs.”

Dew said the first half of the book is about his own experience, the second half is about the slave trade, and the final chapter pulls it all together.

A few Black adults made an impression on Dew as he was growing up. Most prominent was a woman named Illinois Browning Culver, who worked in Dew’s family home for years cooking and cleaning.

Dew and his brother grew up thinking of her as an authority figure. Years later, on break from Williams College in New England, Dew drove Culver home. Trying to make conversation, he said it was a shame her son couldn’t find a job in St. Pete because of race.

After a long pause, she agreed it was a shame, and that exchange broke the ice between them and allowed for more conversations.

He learned from her that Black people were not allowed to sit on the green benches placed strategically downtown. He also didn’t know that black people could buy clothes in the department stores downtown but could not try them on in the store. If it didn’t fit when you got home, you couldn’t bring it back for an exchange.

“I was able to talk to her and discover a lot about how she was in effect forced to live in St. Petersburg as a second-class citizen.”

At the core of “Making of Racist” is Mrs. Culver’s question: “Charles, why do the grownups put so much hate in the children?”

That’s when Dew knew racism and acceptance of the Jim Crow culture was passed on from generation to generation “almost like a genetic trait.” He credited her with giving him this revelation and dedicated the book to her.

Dew said whether you were Black or white growing up in the South, there was a moment when you realized the power of race. His moment came in 1945 when Bill Williams came to his house.

Mr. Williams owned a shoeshine parlor in downtown St. Pete. Dew’s father, a prominent attorney, went there to have his shoes shined. One day, after overhearing an exchange between Black shoeshine workers, Dew’s father stormed off.

Mr. Williams came to their house to apologize, and Dew’s father “exploded in rage.” The reason? Instead of the back door, Mr. Williams came to the side door, a violation of one of Jim Crow’s most ardent rules.

Reese revealed that Mr. Williams was the only Black person to own a business in downtown St. Pete, which was located in the arcade between Central and First Avenue around Fourth and Fifth Streets. Jews were also not permitted to own businesses downtown.

“I absorb that culture. A lot of it was non-verbal in structure,” Dew said. “You grow up in this culture as a white person, and you learn this as the sort of modus operandi – that this is the way society is structured, and this is the way you are supposed to behave.”

When asked the most painful moment in writing the book, Dew recalled a story from his Williams College days. When he was telling a racist joke to some students in the dorm with the door open, a Black student walked by, and Dew realized he could have been overheard.

The next day, he found the student and shook his hand — the first time he shook hands across the color line. The student had not heard his joke.

“That was the first moment that the cultural baggage that I had brought North with me was really revealed to me, and I didn’t wash that out of my system overnight; it was a slow evolutionary process. But gradually, over four years, I came to see that this culture I grew up with was poisonous and was toxic.”

Dew said the impetus for him to study Southern history was to understand how he was able to grow up in the Jim Crow South, where segregation was omnipresent, and be oblivious to its implications.

He said we need to think critically and constructively about our society because we live with systemic racism.

“It’s not enough to say I’m not a racist,” Dew said, referencing author and historian Ibram X. Kendi. “You have to be antiracist; you have to challenge policies and structures that are clearly discriminatory.”

The next Community Conversations will be held Wednesday, Feb. 17, at 6:30 p.m. Visit the Tombolo Books “Events” page, scroll down to the Community Conversations event, and click the Google Forms link to register.