The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg hosted an update on the structural racism study commissioned by the City of St. Petersburg. The Oct. 14 virtual discussion showed an acute challenge as a community regarding race and racism. Principal investigator and USF professor Dr. Ruthmae Sears (pictured) walked attendees through the two-hour presentation.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg hosted an update on the structural racism study commissioned by the City of St. Petersburg. The Oct. 14 discussion, moderated by Carl Lavender, Jr., featured community members and the research team, including Mayor Rick Kriseman and principal investigator Dr. Ruthmae Sears, USF professor.

Mayor Kriseman said the city had made strides in dealing with racial equity. However, there is still a lot of work to do, noting that the city commissioned this study to document the history of racism in this city objectively.

“Opportunity cannot be realized until we look back and document our full story,” he said. “There have been abuses of power that have led to unequal treatment and inequitable outcomes. We are being intentional that such transgressions do not happen again.”

One of the study outcomes is to show how structural racism impacts Black lives and the St. Petersburg community. Structural racism reinforces inequities and discriminatory actions that affect the overall quality of life.

“Racism impacts every aspect of our lives: personal, institutional, interpersonal, and structural,” Sears said. “It can impact the quality of education, individuals you interact with, institutional opportunities, and advancement professionally.”

Barriers in education, healthcare, housing, and the legal system can also impact your opportunities, she noted.

Members of the community chimed in to share their observations and experiences with racism. Nashid Madyun, from the Mississippi Delta and new to St. Pete, said his experience has been generational with the emergence of African Americans as business owners and contributors to society.

“I’ve witnessed people simply ignore, exclude, or be aggressive — using violence, actually –to deter any type of Black political activity,” he said.

Debra Thrower related that her experience has been as a social worker in nonprofit organizations. She was a supervisor working with leadership that did not represent diversity at all, she explained. She experienced microaggression, being asked to leave meetings when decisions were being made, whispering, and exclusion.

Co-founder of Estrategia Group Jessica Estévez, who is also Dominican, recalled the first time someone told her she had a “good tan” and said they didn’t expect her to speak so eloquently.

Rebecca Watson told how her son experienced racism in school during his eighth-grade year. His peers called him the n-word and “monkey.” She spoke with the school principal, who told Watson she would engage a plan with teachers. Watson later found out the principal never talked to the teachers, and nothing had been done.

“That happened in 2015, here in Pinellas County,” Watson said.

Pastor Louis Murphy said he’d been around when schools were segregated and then integrated, so he has seen a lot of racism.

“African Americans can be in a position to make decisions, but I see minority businesses can still be disenfranchised and excluded,” he asserted. “Case in point: the procurement director of the City of St. Pete for the past 40 years was an African American, but the percentage of city dollars going to minority businesses was absolutely shameful. So, we really do have to dismantle this structural racism.”

As to what can be done to address and dismantle racism, Pinellas County School Board member Caprice Edmond said it would be a good idea to lean on our elected officials more and let them know our expectations.

“We need to communicate with all elected officials, not just the African American officials,” she said, “because it takes the majority to approve anything.”

As a city official, Susan Ajoc interacts with many different groups, and when she hears people refer to Black people as “those people,” she calls them out on it, she said. As a person of color, Ajoc tries to provide information and a sharing of culture and ideas and looks at ways to learn more about each other and not make assumptions.

Geveryl Robinson, who teaches at USF St. Pete, pointed out that not everyone wants to dismantle racism, adding that if they wanted to, they would, but they benefit from it and do not want to admit it or want it to end.

“Racism is profitable and is comfortable for a lot of people because they benefit from it,” she said.

Sears shared some of the critical findings of the study, noting there were three outcomes:

- Giving a historical overview and data trends to illustrate the impact of racism on the St. Pete community

- Providing recommendations for policies practices to help dismantle racism

- Identifying additional features of structural racism impacting Black residents in St. Pete that may need further research, documentation and solutions

St. Pete has a well-documented history of segregation that limited opportunities to Black citizens. In 1868, the first African American settled in St. Petersburg. The black population grew during the last stages of the Orange Belt Railway and the building boom of the 1920s.

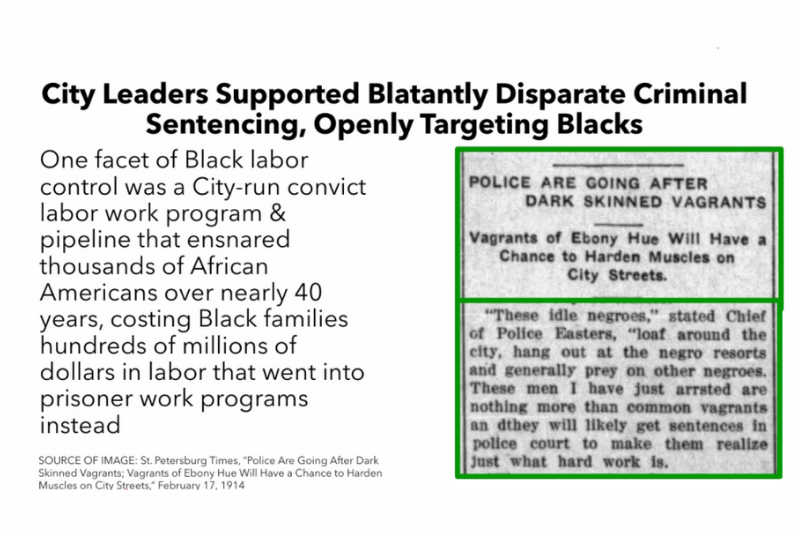

As the Black population grew, local policies were created that built structural racism. Aggressive vagrancy laws fueled a city-run convict labor program and work crews. Between 1910-35, although African Americans made up 18 percent of the population, they were 82 percent of the hard labor.

The KKK intimidated the community with lynching, and police brutality was extensively documented as abusive behaviors were normalized. In 1968, sanitation workers went on strike for better wages and working conditions.

Public office and politics fueled discriminatory practices. Some politicians publicly affirmed their commitment to racist ideology. In the 1950s, the white citizens’ council fought school integration. There was no Black representation until 1969, which impacted the development of equitable and inclusive policy, Sears explained.

Police enforced segregation and limitations to Black/white interaction decreased the likelihood that Black people could offer their business services to whites. On Oct. 1, 1957, the white council supported economic boycotts of businesses that employed Black people.

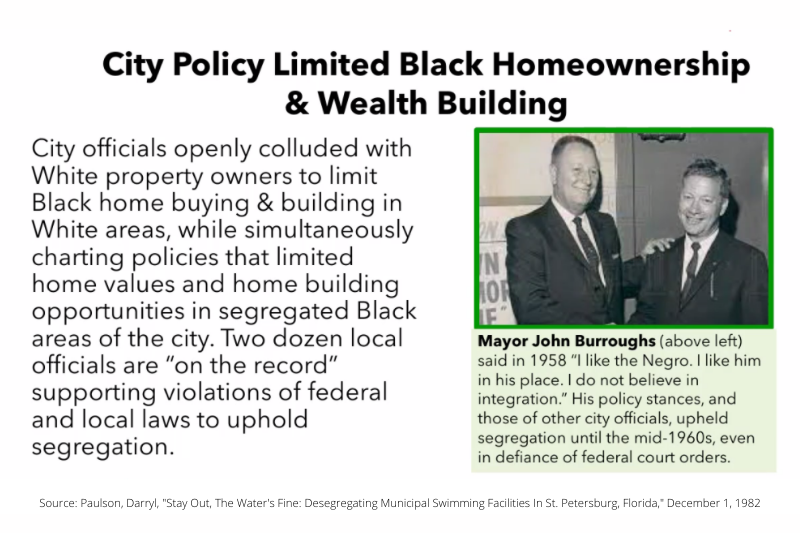

Redlining prevented home buying and building in white areas while changing policies to segregate Black areas of the city. In 1958, Mayor Burroughs said he liked to keep the “negro…in his place.” The council and policies upheld segregation until the mid-1960s in defiance of federal court orders.

City policy controlled the Black workforce, including wage price-fixing, convict labor loan and leasing programs, and local governmental pay disparities for Black workers, including teacher salaries and city-paid death benefits.

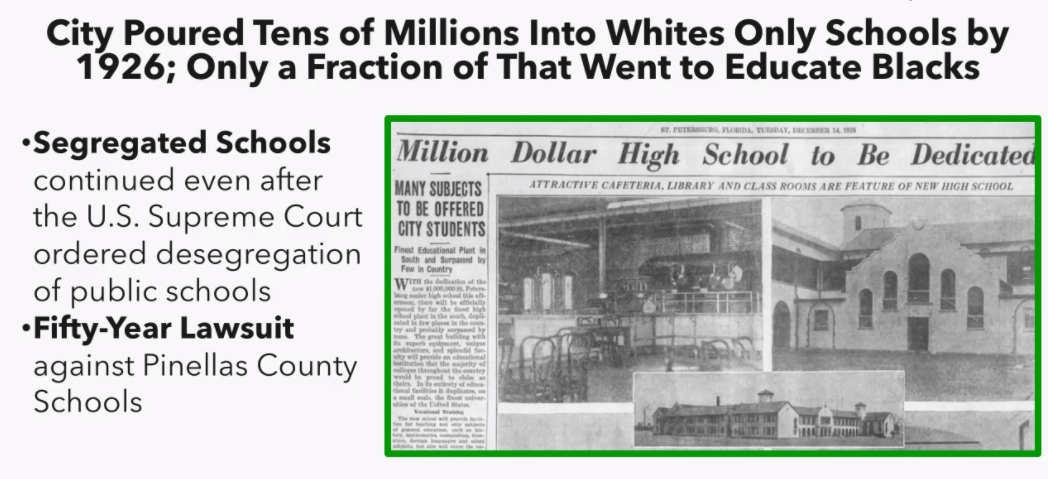

The tax support for Black schools was inadequate, which increased the number of uneducated and impoverished African Americans. Money was poured into white schools while only a fraction went to educating Black students, a practice deemed a normal state of affairs by white city leaders.

St. Pete continued to promote a segregated environment until 1971, despite federal laws. The city was the first to use the busing system to demote segregation. Pinellas County engaged in the 50-year lawsuit regarding educational disparities pertaining to graduation rates, proficiency on state assessments, participation in accelerated classes, school discipline, eligibility criteria for special education programs, and increasing staff diversity.

In 2017, the case was mediated, which resulted in the Bridging the Gap plan. In 2015, the Tampa Bay Times featured a series titled “Failure Factories,” which documented the lack of funding for Black students.

Quality of healthcare is also tied to race. Although there was a public hospital in St. Pete, it was not accessible to Black citizens. Mercy Hospital was opened for the Black community, which was inadequate.

St. Pete’s Black community struggles with health disparities from birth and is likely to have a lower life expectancy rate. Except for lung cancer, Blacks exceed all other races for all leading causes of death. Economic disparity is associated with quality healthcare.

The gap in life expectancy exists across Pinellas County. For example, the average life expectancy is 16 years less in the Campbell Park area than in Old Northeast or Snell Isle.

Income is consistently lower, no matter the number of degrees, for all careers. For example, in 2016, the median annual income for non-Hispanic blacks was 67 percent of whites.

Sears proposed creating an equity department with the mayor’s office. The office director will have a permanent seat at each successive administration’s table for all meaningful decisions and outcomes.

The role of the director would include an annual equity assessment with input from the community, liaising with the budget committee to negotiate adequate funds for needed city projects, and staying on top of data to bring important issues to the notice of the city and its residents in a timely fashion.

Sears’ recommendation is consistent with newly proposed amendments to the City Charter, specifically proposed Amendment 3.

Secondly, create and implement an effective accountability strategy supported by measurable outcomes that are tracked over time with disaggregated data, allowing the city to monitor and incrementally improve progress and performance until equitable outcomes are achieved. This should include a commitment to a race equity review of existing city policies and practices and of all future proposed policies and procedures.

Finally, create a permanent resident race equity board or commission to help ensure the sustainability of the recommended transformation, inform, and drive continual progress. The performance monitoring by and input from this resident commission will increase the likelihood that informed, continuous improvement toward equity will become part of the organizational structure and culture.

It is recommended that this becomes a permanent way of conducting business in the city.

Like other residents, Kathy Wagner said she agrees with the recommendations and is curious where the action comes in and what needs to be done with the schools, police departments, etc. Sears said this is where we need the people’s voice, and as we work with the council, it is up to the community to make sure it happens.

“After elections and we have a new leadership team, the goal is to extend the work and support systemic changes,” she said.

Local historian Gwendolyn Reese pointed out that the influence of the people should not wait until a new administration to be felt.

“Your action is needed now,” she said. “You can start now by calling the council members and letting them know you support the recommendations. I feel that these recommendations are action items.”

Diversity, equity and inclusion team:

- Ruthmae Sears, principal investigator & USF professor of mathematics

- Johannes Reichgelt, professor of information systems and decision sciences and director of the Institute for Data Analytics and Visualization

- James McHale, professor, and chair of the Department of Psychology and director of the USF Family Study Center on the St. Petersburg campus

- Gypsy Gallardo, CEO, 2020 Plan & One Community Plan

- Tim Dutton, Unite Pinellas

- Fenda Akiwumi, co-principal investigator, USF professor of geosciences & director, Institute of Black Life at USF

- Dana Thompson-Dorsey, co-principal investigator, professor of education, & director, David C. Anchin Center

- Michelle Bradham-Cousar, study project manager

- Gwendolyn Reese, president & CEO of Peaten Reese Peaten Consulting, Inc., & president of the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, Florida

- Jabaar Edmond, community partner & program director, CDAT Center

- Jalessa Blackshear, student collaborator

- Casey Lepak, student collaborator