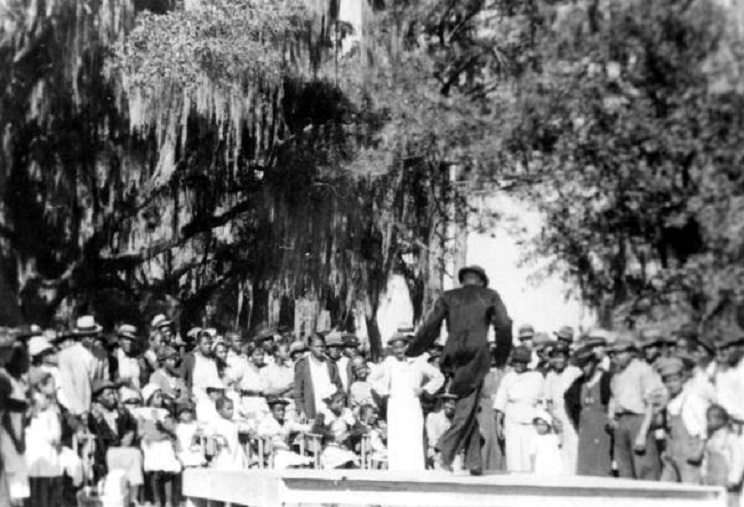

On June 15, 2021, the U.S. Senate passed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act by unanimous consent. Pictured is a 1922 Emancipation Day gathering in St. Augustine.

BY JIM SCHNUR, Contributor

Known as the oldest commemoration to recognize the end of enslaving Black people in the United States, Juneteenth marks the anniversary of an order U.S. Major General Gordon Granger issued in Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 1865. In part, General Order No. 3 proclaimed that “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves.”

General Order No. 3

Granger’s order officially ended slavery in Texas, the most remote state within the former Confederacy. His authority came through the Emancipation Proclamation that President Abraham Lincoln drafted during the Civil War. Issued on Sept. 22, 1862, Lincoln’s executive order changed the status of between three and five million Black Americans from enslaved to free, within the states that had seceded, beginning on Jan. 1, 1863.

The Union’s victory on April 9, 1865, after Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender, allowed the Emancipation Proclamation to take effect in the former Confederate States. However, the collapse of Confederate forces happened at different times in each secessionist state.

Fighting continued in some areas after April 14, 1865, the day that John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre. Lincoln died the following morning. Texas became the last state to learn of the war’s end with Granger’s notice at Galveston on June 19.

A Time of Jubilee

In the years immediately following the Civil War, annual celebrations to commemorate the end of slavery occurred on many different dates. Known in some communities as “Emancipation Day,” these celebrations also carried the name “Jubilee” in recognition of the freeing of Hebrew prisoners and slaves noted in the Book of Leviticus.

St. Augustine Emancipation Day parade float for St. Paul AME Church in 1922.

Although most of us celebrate Jan. 1 as New Year’s Day, formerly enslaved persons during the years immediately following the Civil War sometimes referred to Jan. 1 as “Jubilee Day” to honor the anniversary of the date the Emancipation Proclamation took effect.

In addition to Jan. 1, Black communities throughout the former Confederacy frequently celebrated Emancipation or Jubilee Day on anniversaries connected with the end of slavery in their areas. Some also chose to gather and reflect on June 19, July 4 or Sept. 22.

Florida’s Juneteenth

More than a month after Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, Union General Edward M. McCook reached Tallahassee on May 10, 1865. Five years earlier, Florida had a population of 140,424. Almost half of the people living in Florida when the Civil War began in 1861 were enslaved individuals who lacked any rights of citizenship.

A May 20 Emancipation Day gathering at Horseshoe Plantation, near Tallahassee, more than 90 years ago.

Hillsborough County included present-day Pinellas and neighboring areas at that time. Fewer than 3,000 people lived in the greater Tampa Bay region at the beginning of the war. Many fled during the war, and the region actually saw its population decline by 1865.

McCook arrived in the only Confederate capital east of the Mississippi River that had not surrendered to Union troops during the war (although the Union did take Key West). He took up headquarters in a Tallahassee home built in 1843, later known as the Knott House, for the family that lived there from the late 1920s until 1985.

On May 20, McCook read the Emancipation Proclamation and officially proclaimed that the practice of slavery had ended in Florida. Our state’s Juneteenth, its official Emancipation Day, is May 20. In recent years, annual May 20 celebrations have taken place at Tallahassee’s Knott House, a short distance northeast of the capitol.

Early local celebrations

Early emancipation gatherings happened on different days. The July 6, 1867, issue of the Florida Peninsular mentioned a biracial, harmonious Tampa assembly on July 4: “In the evening the freedmen seemed to enjoy the occasion as we observed them marching through the streets with the United States flag at their head and singing some of their favorite airs, accompanied with instrumental music.”

The 1843 Knott House, a historic structure in Tallahassee that is now the site of Florida (Juneteenth) Emancipation Day events.

By 1870, Tampa’s Emancipation Day celebration moved to Jan. 1. A gathering took place at the county’s small courthouse as people assembled to hear Black speakers and sing a variety of songs, including “Old John Brown.” Jan. 1 remained the primary date for Tampa celebrations during the 1870s, a time when fewer than 10,000 people lived in the region.

Challenging sources

Newspapers offer an important source for historians. Unfortunately, only a handful of local publications from the late 1800s exist. Tampa’s primary newspaper from the time, the Florida Peninsular, did not look favorably on the activities of the freed persons during the 1860s and early 1870s. Many stories that referred to Black people had a derogatory tone.

For example, a story in the Jan. 8, 1869, Florida Peninsular complained that Tampa’s Black community had gained too much access to the Hillsborough County Courthouse: “A printing office, Negro schools, Negro preaching, and Negro balls are all allowed at the Court House. Who pays the taxes to keep up the Court House? The white people of Hillsborough County.”

For a brief period in late 1868 and early 1869, a newspaper known as The True Southerner competed for readers in Tampa. Published in the courthouse with a masthead proclaiming, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal,” this paper supported efforts to assist the freed persons during Reconstruction.

The editor of the Florida Peninsular referred to his publication as the “white man’s paper” while condemning The True Southerner with pejoratives like a “[pejorative deleted] nose rag.” Unfortunately, negative accounts of Emancipation Day events continued late into the 20th century in other local newspapers.

Challenging times

May 20 remained the primary day to celebrate emancipation in Tallahassee from the 1880s forward, with many other Panhandle locations choosing that date by the 1890s. After Reconstruction ended in 1877, these gatherings became more subdued. Few, if any, white people participated as new demands for racial segregation poisoned much of the nation.

Reenactors portray the 1865 reading of the Emancipation Proclamation at Tallahassee’s Knott House 150 years later, in 2015.

American school textbooks may have mentioned the Emancipation Proclamation’s effective date of Jan. 1, 1863, but writers and historians of that time largely canceled any discussion of the significance of May 20 in Florida and June 19 in Texas for new generations of students.

The earliest mention of an Emancipation Day gathering in St. Petersburg from existing sources came from a May 25, 1901, issue of the St. Petersburg Times (now Tampa Bay Times). Crowds came by train from Clearwater and boats from Tampa on May 20, and the “beauty and chivalry of the colored population turned out” during a bicycle race, baseball game, picnic, and other events.

Called “a day dear to the hearts of all Negroes” by the St. Petersburg Times, the May 20, 1906, celebration offered a chance for Black residents from throughout the region to gather for a large picnic at Veteran City, present-day Gulfport. The paper reported that “the crowds were very orderly and only one row occurred and the participants in that were speedily arrested by an officer.”

When white-owned papers did (infrequently) mention these events, they often added humiliating or denigrating commentary. For example, a 1912 Emancipation Day article carried the headline, “Colored Excursion Gives Cops Something to Do.”

Juneteenth: A day to remember

While existing sources illustrate that the Black residents of St. Petersburg and Clearwater generally celebrated Florida’s Emancipation Day on May 20, some communities continued to hold their events on Jan. 1. For example, Black residents in Seffner in 1924 and Arcadia in 1930 — along with the Tampa Ministerial Alliance in 1933 — combined Emancipation and New Year’s Day celebrations.

During this period, Black tourists could not visit most Florida beaches or roadside attractions. This included Silver Springs, a popular site northeast of Ocala that has featured glass-bottom boats since the late 1800s. In 1949, Paradise Park opened for Black guests a short distance from the original Silver Springs. Knowing the importance of Emancipation Day, park operators chose May 20 as the attraction’s opening date.

An automobile decorated for the 1922 St. Augustine Emancipation Day parade.

The significance of Juneteenth gained greater importance during the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, especially after the Poor People’s March on Washington in 1968. Wanting to bring greater attention to the needs of Tallahassee’s Black community, more than 75 students walked out of that city’s Leon High School as an Emancipation Day protest on May 20, 1970.

Although gatherings on May 20 and June 19 continued during the 1970s and 1980s in Florida, they tended to be smaller assemblies rather than larger, sponsored events. Texas recognized Juneteenth as a state holiday in 1980, and neighboring states began to honor June 19 in subsequent years.

Juneteenth Florida days to celebrate

On Oct. 1, 1991, Governor Lawton Chiles of Florida signed a bill into law that recognized Juneteenth Day. Officially known as Chapter 683.21, Laws of Florida, this measure called for “public officials, schools, private organizations, and all citizens to honor the historical significance” of June 19. Since 1992, St. Petersburg and other Florida cities have held events on June 19 to celebrate Juneteenth.

Precursor to Juneteenth: Florida Emancipation Day celebration at the Knott House Museum, Tallahassee, on May 20, 2015.

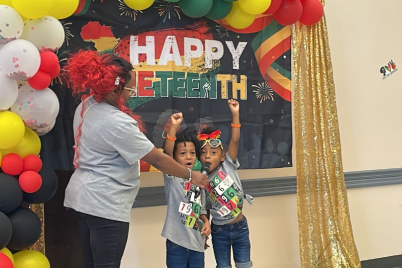

In a rare example of quick Congressional action, on June 15, 2021, the U.S. Senate passed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act by unanimous consent. The following day, the U.S. House approved the measure by an overwhelming margin. On June 17, 2021, President Joe Biden signed this law into effect, creating our newest federal holiday.

Although many Americans will honor the significance of emancipation on June 19, some will always remember that May 20 is also a pivotal date in Florida’s history.