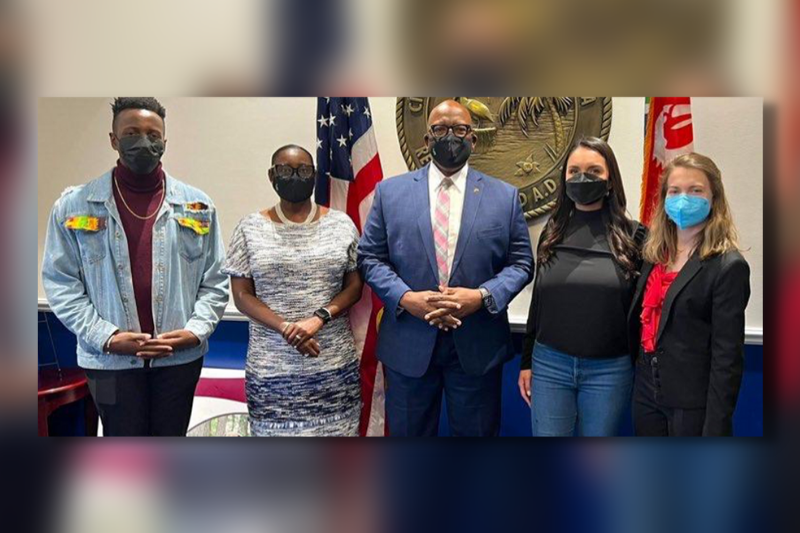

The comprehensive affordable housing study was completed by a team of students from the Harvard Kennedy School. Left, Brandon McGhee, first year Master in Public Policy student at the Harvard Kennedy School, Deputy Mayor Stephanie Owens, Mayor Ken Welch, Larisa Barreto, first year Master in Public Administration student at the Harvard Kennedy School, and Bethany Kirkpatrick, Master in Public Policy candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School.

ST. PETERSBURG — On Monday, Mayor Ken Welch and his administration rolled out results from a comprehensive, affordable housing study completed by a team of students from the Harvard Kennedy School.

The study evaluated the city’s existing challenges with affordable housing, possible solutions, and future information-gathering needs.

“The information in this study is comprehensive and will help my administration further our goal for enhancing and expanding our focus on housing affordability,” said Welch. “As you all know, increasing access to affordable and workforce housing was a top priority in my campaign, and it remains a top priority in my administration, now into its second month.”

The release comes after the mayor attended the Restoring the American Dream Affordable Housing Conference with Deputy Assistant Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Alan Williams, led by Pinellas County Commissioner Rene Flowers. There, local policymakers, community, and non-profit leaders identified a sense of urgency on addressing the current housing crisis and established the need to draw down federal and state dollars while emphasizing innovative solutions.

The newly released study sought to answer four questions: What does affordable housing mean for St. Pete, what factors have caused St. Pete’s current housing crisis, what policies are most effective/ineffective for addressing housing affordability, and who do various policy options serve, and who do they exclude?

What does affordable housing mean for St. Pete?

Nearly one-half of renters in St. Petersburg, and a quarter of homeowners, are cost-burdened, which is defined as spending greater than 30 percent of income on housing. Worse, 11 percent of homeowners and 23 percent of renters spend more than half their income on housing.

That cost burden worsens for lower-income households. A total of 51 percent of homeowners earning at or below 50 percent AMI spend more than half their income on housing. For renters, that number skyrockets to 69 percent.

What factors have caused St. Pete’s current housing crisis?

The price of new rentals in St. Petersburg jumped nearly 25 percent in 2021, the third-highest increase in the entire country.

One reason for the increase in prices is that supply has not caught up as demand for housing has increased. The study found that from 2020 to 2021, investor residential land purchases increased by 79 percent. From 2011 to 2021, residential investor purchases increased 520 percent.

The influx in investor activity is likely making it more difficult for individual home buyers to find homes, as investors have access to cash purchases or other quick turnaround closings more attractive to sellers than with conventional buyers who must navigate lengthy financing and approval processes.

What policies are most effective/ineffective for addressing housing affordability?

Rent Stabilization, also known as rent control, limits the increase of rental prices. The measure seeks to maintain affordable housing and limit disruptions caused by rapid rent increases. This method would respond to immediate affordability concerns and halt rental increases for one year, but it has limitations.

The State of Florida preempts rent control policies in effect for more than one year. Additional language in that law places a high burden on local governments to establish the need for rent control, a bar that would require evidence showing a housing emergency was severe enough to constitute a serious menace to the general public and that rent control is needed to alleviate that menace. That language would open any city ordinance to potential legal challenges, on which legislation places the burden of proof to defend the ordinance on the city.

If the city were to move forward with such a measure, the study identified key steps that would need to be taken, including setting an approved increase rate, selecting an enforcement infrastructure, and determining a voting timeline (state law requires a citywide vote to approve rent control).

The study also identified alternative routes that could be pursued to lower rents, including incentivizing landlords, publicizing housing affordability efforts, educating stakeholders, protecting vulnerable citizens through targeted initiatives, and addressing residual income burdens such as childcare, transportation, health care, and food insecurity.

Upzoning is a process by which governments can change codes to increase the amount of development allowed at a particular site or in a specified area. This often refers to what is known as “the missing middle,” multi-family housing that is smaller than a traditional apartment complex, such as duplexes, triplexes, and accessory dwelling units.

Benefits of upzoning include increased housing supply and density, positive climate effects through additional density near public transportation and work centers, and slowed neighborhood displacement by allowing residents to stay in their neighborhoods at more affordable rates.

But there are drawbacks as well. Upzoning policies don’t require developers to utilize them. And if developments are constructed at market rate, it would do little to solve affordable housing challenges.

The study found that in New York City, only 19 percent of completed housing units were considered affordable since the city began upzoning in 2014. Of those affordable, only 28 percent served households at 50 percent AMI and below.

Upzoning in low-income neighborhoods could also be a drawback, as those areas already contain the highest density of affordable housing. Instead, successful upzoning occurs in middle- or upper-income neighborhoods lacking affordable housing options.

Inclusionary Zoning is a method that requires market-rate developers to also develop affordable housing. Such policies can allow for flexibility, including setting affordable housing requirements as a percentage of overall units, developing those affordable units at an alternative site, or paying fees or donating land instead of developing affordable units.

Like rent control, the city is limited in what it can enact due to state legislation, which requires local governments to “provide certain incentives to fully offset all costs to the developer of its affordable housing contribution.”

But there are available tools, including density or intensity bonuses, reducing or waiving fees, or other types of incentives.

The city has already begun utilizing this method, increasing the amount of funds available to developers to construct affordable housing for residents earning less than 80 percent AMI (and in some instances, less than 120 percent AMI).

Land Banking is a process by which local governments, public authorities, or nonprofits can acquire land to redevelop property and return it to productive use, including as affordable housing.

St. Petersburg already utilizes land banking through its Affordable Housing Lot Disposition Program, which connects qualified developers to city-owned vacant lots for development. The study found the city could expand that program by purchasing vacant lots or homes for sale by private owners.

The study further found opportunities to incentivize developers through land banking programs with waved impact fees, expedited permits, pre-approved architectural plans, or reduced or modified development requirements.