Panelist Fred Hearns, Gwendolyn Reese and Victoria Oldham discussed the Civil Rights Movement in the Tampa Bay area at the opening reception for the Beaches, Benches, and Boycotts exhibition at the Florida Holocaust Museum Sept. 7.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The Florida Holocaust Museum opened its original exhibition Beaches, Benches, and Boycotts: The Civil Rights Movement in Tampa Bay on Sept. 7. The event included a discussion about the history of Tampa Bay’s African- American communities in Tampa, St. Petersburg and Sarasota.

Panelists included Gwendolyn Reese, president of the African American Heritage Association of St. Pete; Fred Hearns, who has served as president for the local chapter of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History and was a longtime member of the NAACP and the Tampa Urban League and Victoria Oldham, a former broadcast journalist and documentarian of Newtown, the African-American community in Sarasota.

Judge Charles Williams, who sits on the board of directors of Embracing Our Differences, Florida Studio Theatre, and The Boxser Diversity Initiative acted as moderator.

Discussing the origins and geographic boundaries of the first African-American communities in St. Pete, Reese noted that we could trace the first such community, Pepper Town, to 1888. It was located around what is today Martin Luther King, Jr. Street, near Third and Fourth Avenue.

“That community was established primarily when black workers came to build the Orange Belt Railroad,” Reese explained.

Methodist Town was another community that followed in 1894, called so because it was built around Bethel AME Church. The next area was Cooper’s Quarters, which became known as the Gas Plant area because of its two large natural gas reservoirs. It extended south of Fifth Avenue to include the Campbell Park area.

“Then, of course, we have the Deuces,” she said. “Everybody knows about 22nd Street and the Deuces, and that was actually the last African-American community to be established.”

There were 111 thriving businesses, black-owned and operated, along with Jewish-owned establishments in a 10 block radius along 22nd Street, Reese pointed out.

Speaking of Tampa’s early community, Hearns went back to May 5, 1864, “the date that freedom came to some 100 enslaved African Americans in Tampa.” Most of those enslaved people lived around the downtown area, which was residential then.

“So those blacks lived close to their masters,” Hearns said.

That was the beginning of what came to be known in the 1890s as the Central Avenue District. Even into the late 1920s, half the African-American population of Tampa still lived in this district.

There were some significant civil rights struggles right here in Sarasota, St. Pete and Tampa, though they did not get the publicity of places such as Birmingham or Selma, Ala.

Oldham spoke of a time in Sarasota when black children could only swim in swimming holes or even a train car full of water, but not on the beach, which was reserved for whites. Then a man named Neil Humphrey, the first NAACP president in Sarasota County, said enough is enough and organized “wade-ins” at Lido Beach in 1955.

African Americans would pile into cars, pick up people along the way, and head toward the beach to take “a stand in the sand,” Oldham said.

“It wasn’t one time that they did it,” she explained, “it wasn’t one year that they did it, but from 1955 until a couple of years after the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed, they were doing those wade-ins for over ten years on Sunday!”

Segregation on the beaches was not even a law on the books, Oldham pointed out, but one of those unspoken Jim Crow laws. After the wade-ins helped change things, it opened up the beaches to countless more tourists.

Reese pointed to the sanitation strike of 1968 as a pivotal moment for the St. Pete black community. Primarily African-American sanitation workers fought for fairer wages, working hours and conditions.

These workers went on strike from May through August 1968 and were represented by black attorneys. They marched down the Deuces on their way to city hall that summer, fighting for their fair due.

“That didn’t come easily at all,” Reese said. “We actually had disturbances. The St. Petersburg Police Department actually had an armored tank that went down streets spewing tear gas.”

Hearns mentioned the sit-in movement as the most significant demonstration in Tampa, notably the efforts of Clarence Ford, a 20-year-old barber in 1960. He was also president of the NAACP youth group at the time. Even the older leaders of the NAACP tried to talk young Ford out of organizing his lunch counter sit-ins, as they did not want to challenge the power structure.

Ford didn’t listen, Hearns said, and went to various Tampa high schools to recruit like-minded young people. These students peacefully sat at the F.W. Woolworth lunch counter for months — in the face of some bullying and taunting — until later in 1960, when the counter was finally desegregated.

“Charismatic leaders served in to inspire, but it is the foot soldiers giving their blood, sweat, and tears that make dreams and ideas a reality,” noted Elizabeth Gelman, executive director of the Florida Holocaust Museum. “One of the goals of this exhibition was to give our local foot soldiers their due. To make sure that people knew their names and got a small sense of who they were.”

Community leaders attending the opening included Sen. Darryl Rouson, Seminole Mayor Leslie Waters and St. Pete Police Chief Anthony Holloway. Rouson pointed out that it is appropriate that the exhibition opens during September when Rosh Hashanah begins.

“It marks the beginning of the Jewish New Year,” he said. “Both a day of judgment for mankind and a time of closeness and reconciliation with God. A time of reflection when we come to understand that the journey traveled by so many of our ancestors has been similar in its cruelty, its inhumanity and its senselessness.”

The original exhibit has made rounds at Bay area schools as well, helping to bring to light the struggles of the civil rights era to today’s young students. Hillary Van Dyke, senior professional development coordinator for Pinellas County Schools said that last year it traveled around various St. Pete high schools and this year it will be shown at St. Pete middle schools.

“Not only has the exhibit been up in these media centers for students to come see, so teachers are bringing their students through,” Van Dyke explained, “we also have built an entire professional development around this particular exhibit, so we are getting the teachers’ hands dirty as well.”

Michelle Anderson, K-8 social studies specialist, said that several teachers have been “shocked and surprised” at what they’ve seen in the exhibit.

“The exhibit does such a wonderful job at building a context for understanding,” Anderson said.

Students can see historical documents for themselves, such as a letter from outspoken activist Robert Saunders demanding a construction company to take the “colored” sign down at a port-o-john at a construction site.

“What we’re ultimately hoping,” Anderson said, “is that it also builds this context for our students so that they understand better the community that they live in and the neighborhoods that they live in, and they have a richer connection to their own history.”

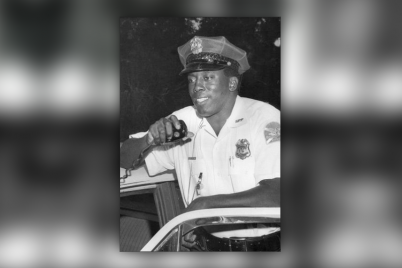

The museum also bestowed its Upstander Award to Leon Jackson, the last surviving member of a group of African-American policemen that came to be known as the Courageous 12. Those dozen officers fought back against the status quo and successfully sued the city of St. Pete for discrimination within the police department in 1968.

Chief Holloway was quick to give credit to the trailblazing efforts of Jackson and the other men.

“Because of Mr. Jackson and those 11 other foot soldiers, or courageous men, I am standing here today before you because of this,” Holloway said, adding that African Americans were afterward able to rise to any rank within the force, not only in St. Pete but in the state and even the country.

The exhibit runs at the Florida Holocaust Museum through March 1, 2020.

To reach Frank Drouzas, email fdrouzas@theweeklychallenger.com