Growing up as a child, Gwendolyn Reese lived in the Gas Plant neighborhood at 1305 Fifth Ave. S, in an enclave called Sugar Hill. She remembers fish fries in backyards, hopscotch on the sidewalks and conversations on the porches.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is an ongoing USF research study that addresses the erasure of historic Black cemeteries in the Tampa Bay area. Awarded a USF Blackness and Anti-Black Racism grant in 2020, it consists of faculty, staff, and students from multiple disciplines across USF St. Pete and Tampa campuses.

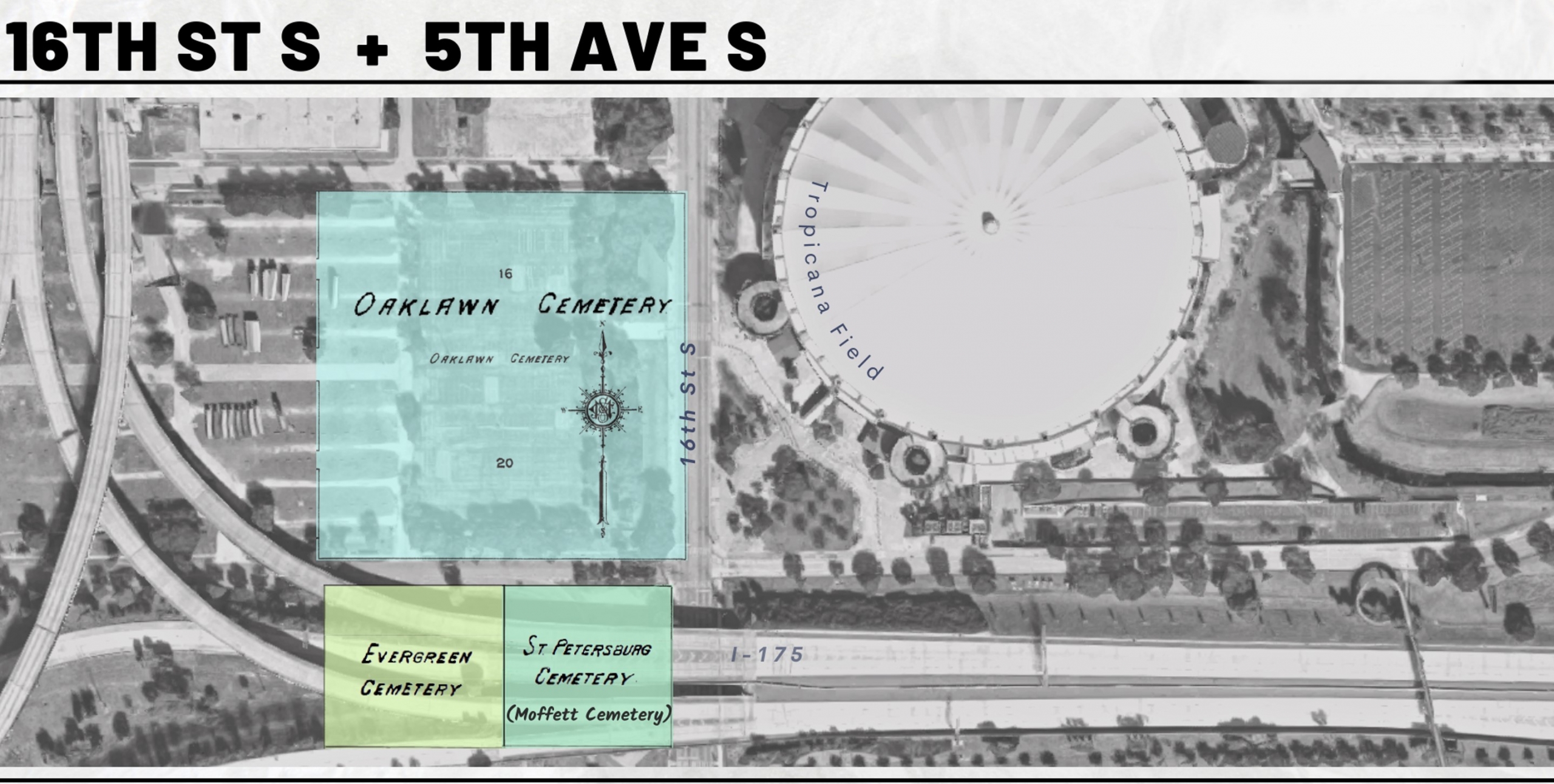

The project focuses on activities to identify, interpret, preserve, record, and memorialize previously unmarked, erased, abandoned, and underfunded African-American burial grounds in Florida, with a focus on Tampa’s Zion Cemetery (located beneath Robles Park Village) and St. Petersburg’s Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries (located beneath a Tropicana Field parking lot and I-275).

One aspect of the African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is recording oral histories of those who remember or are related to those lost to time.

Gwendolyn Reese, president of the African American Heritage Association of St. Pete (AAHA), is a true native of the city, as a midwife delivered her in the home of her uncle, which sat right behind Mercy Hospital.

Although Reese’s knowledge of the “lost” cemeteries — namely the Oaklawn Cemetery complex, which is Oaklawn, Moffett, and Evergreen — is limited, she said she is “almost positive” she has distant relatives buried there.

“Based on the times and segregated cemeteries, and those were the only ones for a time for African Americans, I’m almost assured that I have someone buried there,” she said.

In elementary and middle school, she explained, she and her classmates had direct paths they were to follow from school to home, but as children will do, they often chose to do something “that was a little more exciting or maybe even a little frightening as it comes to cemeteries … the route we would take home would take us through the cemetery.”

When Reese was a child, she lived at 1305 Fifth Ave. S, (Sugar Hill) and her route home was at times through the cemetery — where she always took care not to step on the graves. During these walks, she recalled some headstones were in disrepair, and the grass was overgrown.

“I was walking through the one that would be the southernmost cemetery,” she said. “One of them was a white cemetery, from my memory, and the other two—but I would have been walking through the southernmost cemetery that is very near what is now Unity Temple of Truth and what was then the Episcopalian church.”

Reese remembers growing up in the Gas Plant neighborhood east of 16th Street. She noted that African Americans lived in mixed-income communities because redlining and segregation forced them to live together, regardless of income. She grew up in a mixed-income neighborhood with brick and two-story houses, masonry and ranch-style houses and wooden structure homes.

“Some houses well kept, some in disrepair; some beautiful lawns, some dirt yards,” she recalled. “So, it was just really eclectic in the sense of the structures, the architecture of that time of the different homes. It was just this incredible mixture of all kinds of people, and it was just a rich, very, very rich history.”

The Gas Plant neighborhood was a bustling little community, she remembered, calling it a “safe haven” with fish fries in the backyards, hopscotch on the sidewalks and conversations on the porches. Everyone was willing to help their neighbor out, and doors weren’t locked.

“We stepped out of our neighborhood, and we were faced with segregation, Jim Crow laws, white water fountains, colored water fountains, you can’t sit on the green bench, you can’t try on the clothes,” she said. “But when we were in our neighborhoods, it was — we were free from that. And that, I think, has so much to do with our resiliency and our ability to remain hopeful and our ability to overcome all of the adversities that we had to face.”

Many shops and businesses lined the roads, and McRae Funeral Home was one such business. Reese recalled that it was contracted to remove graves and relocate them to Lincoln Cemetery to make way for construction. Though she now longer attends funerals now, she did recall going to them when she was younger, and too often, it was the only time some family members saw one another.

“Reunions became a major part of our culture a little bit later,” she said. “I mean, I was a young adult when I remembered our families having reunions. And a lot of times, it was said, ‘We have to see each other more than just at a funeral.’ But funerals, almost all family members came, and it was a reunion as well as a homegoing celebration.”

Cemeteries tell the story of a people, Reese explained. They tell the story of a particular family, but because of that family’s connections and links within the community, they reveal the story of a community.

We learn when they were born and when they died, she said, and the quote that the family chooses for the headstone speaks to the person — what their role may have been in the community, sometimes even their occupation or favorite scripture.

“You walk through, and you look at the names of the people and the families, and you start to tell the stories of those people and share those stories with others,” Reese said. “And that’s just another way of keeping the history and heritage and culture of a community alive, not letting it get lost. Telling the stories so they can be passed on and passed on and passed on because we know how important it is to know the history not just of a person, but of a community.”

Reese believes that cemeteries such as Oaklawn, Moffett and Evergreen should be remembered today, as it is crucial for people to realize how cemeteries for people of color, specifically African-American people, were paved over.

“I just so strongly feel that the story of that cemetery needs to continue,” she said. “And so if that means markers very similar to the one we have of the lynching memorial, saying the name of the cemetery, the age of the cemetery, when it was opened and when it ended and what happened to it…all [people] see is the Tropicana Field parking lot, or whatever it is they see, and they don’t realize that there were lives. People lived and died here, and many of those people were major — they were pioneers, and they were major figures in the history of our community.”

Reese firmly believes that it is as vital to value and respect those who are dead as it is to respect those who are still living. And as African Americans, we are struggling — our struggle has never ended—to be respected and valued as human beings in this country, she averred.

“I think cemeteries are just another very important way of valuing and respecting the lives of Black people — of all people, but we’re speaking specifically of African-American people primarily because of what has happened to so many African-American cemeteries and burial grounds across this country,” she said. “Many of them we may never know.”

As more lost and erased Black cemeteries are being discovered across the state and the country, Reese believes this should be a time of recognition, acknowledgment and a time for “preserving the stories, preserving and telling.”

“It’s not good enough to preserve the stories,” she underscored. “They must be told. So, we must not just preserve the stories. We must make a—it should be very intentional to tell the stories,”

Concerning the redevelopment of the Historic Gas Plant Redevelopment area, Reese would favor a marker to commemorate where a cemetery was located.

“I think markers are very relevant, and it’s an excellent way of preserving and telling the stories, particularly if — even if they are isolated markers, and they’re not on a contiguous trail, they would be included in, for instance, a tour that I might be leading of the African American Heritage Trail,” she said.

Murals would be another way to tell a story, Reese explained, but they do fade or get painted over. Markers are much more likely “to be there for years, for decades, maybe for even generations.”

Dr. Julie Buckner Armstrong interviewed Gwendolyn Reese on May 21, 2022.